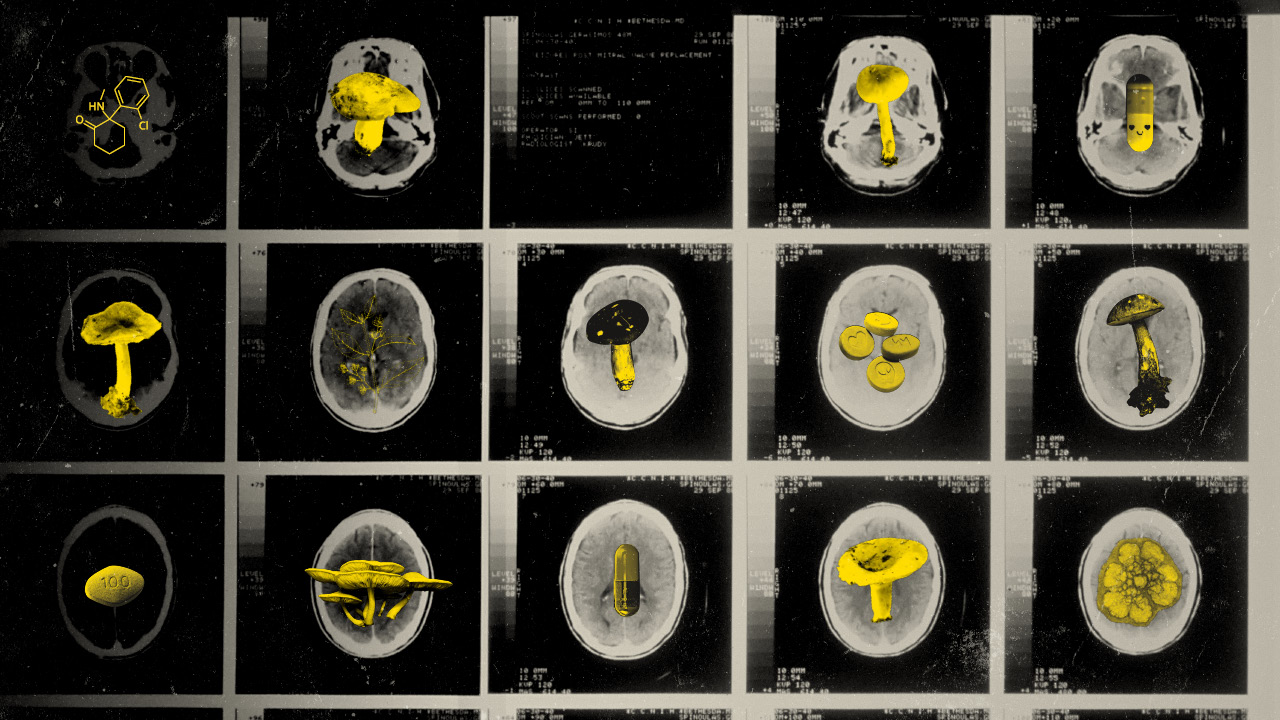

Psychedelics: From ‘Magic’ to Medicinal

Our brains are finely coordinated like computers and what drugs like ketamine, psilocybin do is that they alter the brain's function at that whole network level.

Could psychedelics unlock the answers to managing complex mental health issues?

Once associated with cults and hippies, psychedelics are now becoming an evidence-based treatment for psychiatric disorders. In Australia there are numerous psychedelic trials taking place and as of July 2023, psilocybin and MDMA have been made available for prescription by authorised psychiatrists for the first time. This is on the back of ketamine recently being approved for severe depression.

Who will get access to psychedelics, and what are the ethical considerations of these treatments? Could new psychedelic treatments revolutionise the way the psychiatrists treat mental health, or has the Therapeutic Goods Administration jumped the gun?

Hear from UNSW research fellow and psychiatrist Dr Adam Bayes, Professor Colleen Loo, and Emeritus Professor Wayne Hall as they unpack the stigma, the myths, the benefits, and the path forward in a conversation chaired by Norman Swan.

Presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas, UNSW Medicine & Health and UNSW Science as a part of National Science Week.

Transcript

Norman Swan: Hi, everyone. Thank you very much for coming out. You might notice I'm not Sana Qadar So you're getting a second rate host tonight. Sana is unwell with Covid. I'm not sure why because the pandemic is over. So why would she get it? I don't know. I think she's pretending. Look, welcome to this meeting. And the number of people here today show the interest in this area of psychedelics and psychedelic assisted therapy. Where are we at? Is this overhyped? What's the promise here? And what are the myths and what are the realities? And that's what we're going to cover today.

I'd like to acknowledge country. That we're on Bidjigal land and pay my respect to the Traditional Owners of Bidjigal land. To past Elders, present Elders and emerging Elders. I'd like to pay my respects to any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people here today.

So, look, this is a non-trivial issue. This is an important issue in an area where, unfortunately, in psychiatry and mental health, there have been very few innovations in treatments over a period of time.

There have been some, but not... It's not as if there have been none but not a lot. And complexity is huge. And one of the things I'll say about complexity in mental health is that psychiatrists like to define things very closely. You know, have you've got schizophrenia or you've got schizoaffective disorder? Have you got major biological depression or is it reactive? And you get all these little, these definitions according to various manuals of psychiatry. But for people themselves, the labels matter much, much less than complexity. So you can have depression, but you can be out of work or have no housing, poor transport connections, few social contacts. And that will matter much, much more than the biology of the mental health problem that you've got. And that's relevant to the conversation we're having today, because we're not talking today about psychedelic therapy. We're talking about psychedelic assisted therapy. We're talking about psychedelics, helping the process of therapy, not necessarily being the therapeutic agent themselves.

And it's one of the core concepts that one has, that we will be traversing in this discussion in. We'll also be looking at the history of these. Some of you... It's a pretty young audience so you won't remember Timothy Leary, who was a psychologist who is reputed. But I think Wayne Hall will contradict me here, to be single-handedly responsible for psychedelic research stopping dead. But I think that's one of the myths. With his ‘turn on, tune in and drop out’ philosophy, particularly related to LSD. So our panelists are Professor Wayne Hall, who has a lifelong career as a psychologist and a researcher in drug use and with a strong interest in cannabis, but also alcohol and other drugs, and has written extensively on it. He's assisted the British Parliament with their cannabis policy. Was the second director of the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, which is a research centre at this university and is now an emeritus professor at the University of Queensland, continuing his interest in in drug use.

Then we have Professor Colleen Loo, who is Professor of Psychiatry at this university and also at the Black Dog Institute with a history, with a strong interest in particularly treatment to resistant depression and alternative means of therapies. Ketamine, a growing interest in psychedelic, other psychedelics. We'll talk about whether ketamine is a psychedelic and transcranial magnetic stimulation and innovative therapies. And is a clinical triallist in this area.

As is Adam Bayes, who is also a psychiatrist here at the University of New South Wales and the Black Dog Institute. And in the process of setting up psychedelic assisted therapy at the University of New South Wales. So please welcome our panelists.

This, of course, is part of National Science Week and hosted by the University of New South Wales Center for Ideas, UNSW's Medicine and Health and UNSW Science. I'm wrong in saying that we can blame Timothy Leary totally for the cessation of psychedelic research.

Wayne Hall: Well, he certainly played a role in two ways. I mean, obviously, the sort of his antics that ‘tune in, turn on, drop out’ prompted sort of banning of LSD initially in California and then later nationally in 1970s. He also encouraged the drug company that had the patents on LSD and psilocybin to stop doing research because they thought it was giving them a bad reputation. But there were problems that started well before that, and that had to do with the advent of the FDA requirement that all new treatments were submitted to randomised controlled trials. And most of the people doing the early work weren't interested in doing trials.

Norman Swan: Because they believed it worked.

Wayne Hall: Yes. And it continued beyond 1970, which was when the Controlled Substance Act came into effect. The last of the research in the US ended in about late 1970. So it didn't stop, but it became very difficult. And it was also an area that, if you showed an interest in it, you were immediately suspect, largely because of the example of Leary. Not just Leary. I mean, there was Leary, Ken Kesey, there was a whole bunch of people who were out there doing pretty outrageous things with psychedelics and advocating for their non-medical use.

Norman Swan: But when you've looked at the history, I mean, the history is... So we've got LSD, which is a synthetic substance. I think synthesised what? Late 40s? Is that right?

Wayne Hall: 43 I think it was, yeah.

Norman Swan: For what purpose?

Wayne Hall: Largely as a potential drug in the treatment of cardiovascular disease because it's based in ergot the fungus which has medical uses in control of blood pressure.

Norman Swan: So we're missing something here? Did it do anything for heart disease?

Wayne Hall: No.

Norman Swan: Apart from giving you a heart attack because of the hallucinations that you got.

Wayne Hall: Yeah.

Norman Swan: There's this story the guy on his bike or something like that having taken it before he left the lab.

Wayne Hall: Well, he hadn't taken it. He sent resynthesised it in his lab and absorbed enough through his fingertips to have an experience that he then, he subsequently went on to deliberately take the drug to see if it could be reproduced, because he just couldn't believe that a drug in such small quantities and micrograms could produce experiences that were so profound. So that's Hofmann, the story about.

Norman Swan: But then you've got, you know, in the 60s and 70s, you had writers like Carlos Castaneda writing about mescaline in Mexico. And, you know, people were taking peyote seeds. Yeah. I mean, how real is the use of psychedelics or substances with psychedelic effects going back in history?

Wayne Hall: Well, well known, I guess, in Central America, in the Americas, the cactus, various cactus, the peyote cactus and other cactus. Ayahuasca in Brazil. So there's a variety of plant based drugs that have been used for these sorts of experiences, usually in the context of sort of quasi religious therapeutic settings. So, I think the point we should make about early psychedelics is that it was the 1950s that people started to use LSD therapeutically and in the treatment of alcohol dependence, not the sorts of disorders that we're looking at now.

Norman Swan: Which is interesting because there's one of the uses that people are suggesting for MDMA and psilocybin is in fact for addiction.

Wayne Hall: Yeah, yeah. There's a lot more interest and renewed interest in that. Most of the work has been done around intractable depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Norman Swan: So does it work? Did LSD show promise in alcohol use?

Wayne Hall: Well, there's been analyses done of the early trials, and I think the short story is that people have a profound experience and often do make a serious effort to do something about their drinking. But the longer you follow them, the less effect there is. And in the control trials that were done in the 50s and 60s, by the end of about 12 months, there was no real difference in outcome between people given LSD and those who weren't. The the other aspect of it wasn't just the drug. They were trying to induct people into AA. The Alcoholics Anonymous. And this was seen as a shortcut way to appreciate the wisdom of a higher power. The first two steps.

Norman Swan: So the first of the 12 steps was swallowing the LSD?

Wayne Hall: Yes. And then joining AA and going through that.

Norman Swan: Right. Okay. Colleen, do we know what a psychedelic is? What is it? I mean, how is it defined? Is there something specific that it does to the brain?

Colleen Loo: So I guess it really alters your state of consciousness and your experience. So you're still conscious, but the way you perceive what is happening around you and the experience you go through can be quite unusual. So, for example, with, starting with ketamine, which I've had the most experience with, which is sometimes called an atypical psychedelic. People report all sorts of things. One is that they report altered perception. So often that colours are more vivid, more bright. The space around you might look distorted, the angles of the room look different, your own body might feel different. But people also then talk about all sorts of things coming into your mind. And in some ways it's not that dissimilar to say, dreams, that I think it's almost like the control center of your brain is temporarily put to one side and all sorts of things bubble up, which can take a variety of forms. It could be quite exciting, it could be quite frightening. And I think in the same way that our brain brings up all sorts of things during dreams, when your conscious mind is put to one side, that can also happen during ketamine and during the psychedelic experience.

Norman Swan: People talk about the, what is it called? The default mode network, basically a network of activity in the brain that suppresses cross-talk in the brain and allows you to focus your activity and that psychedelics lift that lid if you like, and allow cross talk in your in your brain. Is there any research to support that? I mean, is this a real thing?

Colleen Loo: There is. So you can do brain imaging studies where you image the activity of different parts of the brain, which is usually very finely coordinated. Our brains are like, you know, very amazing computers. And what drugs like ketamine, psilocybin, other drugs do, is that they do alter the brain's functioning at that whole network level. So you're perfectly right, that usually when this part is active, that part might be suppressed so that you're experiencing things in a very orderly fashion, whereas here different parts might be firing at once and you get this kind of unusual, sometimes cacophony of experiences that are disjointed. That's at one level. And another level, at a microscopic level, we also know that a lot of the psychedelics actually strongly promote neuronal growth and including the growth of new connections. So it also makes the brain, we think, more plastic, which is where it might be quite useful in being combined with therapy. So both breaking out of set ways of functioning and thinking at a brain level, but maybe also the brain cells becoming more plastic to learn new things.

Norman Swan: Adam, some people have said that that idea of the default mode network is also the source of side effects of the drugs and where certain types of people who might, you might want to take care. So, for example, if you're depressed or you have a kind of depressive approach to life, the default mode network is pretty heavy handed on your brain. Whereas if you are more creative and maybe you've had the odd psychotic event during your life, the default mode network is light on. And therefore, if you're going to lift the lid with a psychedelic, you're taking more risk with some people than others. Is that a thing?

Adam Bayes: Yeah, that's a great question. I think what you say is correct in terms of disorders like depression, et cetera. There's a suggestion that there's this overactive default mode network and and so people can kind of get stuck in this rumination. There's a sort of fixed way of thinking. So we know depressed, people with depression, we might think their circumstances are sometimes OK. You know, they feel like the world... They feel negative about themselves, the world and the future. And it could be that there's this overactivity of the default mode network. For those, I don't know there's a lot of, necessarily data on the default mode network activity in patients with psychosis and schizophrenia. But certainly, you know, in the area of psychedelics, we would want to be be pretty careful. And for example, you know, the studies that I'm involved in, those individuals that have a history of psychosis or even a family history in first or second degree relatives, wouldn't be included in a trial because there would be the concern that perhaps it could exacerbate the illness.

Norman Swan: Wayne, you've spent your life studying drugs with the potential for abuse. To what extent do these drugs have the potential for abuse?

Wayne Hall: Well, it depends on what you mean by abuse. I think in terms of addiction, the risk is pretty minimal. You don't see people presenting to treatment services requesting help with psychedelics of various sorts. I think there have been problems around ketamine, but that's sort of more around recreational use and sustained heavy use that people get involved in. I haven't seen a lot of that with, with LSD. If we look historically, the sorts of things that tend to pop up are what Adam's talked about. People with psychotic illnesses taking these drugs and being made a great deal worse. So I think there are some people who are vulnerable to their adverse effects on their mental health. I think the other concern is around the suggestibility and plasticity that Colleen talked about. That people are very open to persuasion. And if the person doing the persuading is not very ethical, you can end up with people being abused and and exploited. And I think historically, there's been a tendency for cults to form around these drugs.

You mentioned Castaneda. He formed a particular group and he was exposed as a plagiarist and a fraud. Subsequently, there was infamously Charles Manson, but the Orange People were fuelled in that case by MDMA rather than the more traditional psychedelics. And a fairly notorious case in Melbourne of The Family, which was where LSD was used to indoctrinate and abuse children and other adults. So I think, you know, the drugs can potentially be used for good in therapeutic contexts when carefully done under supervision and with carefully selected patients. I think the risks are when it's out there in the wild and you've got people using it in ways that are put others at...

Norman Swan: I want to come back to this later, but I want to make the point at the moment that we're talking about psychedelic assisted therapy. So we're talking about the drugs helping psychotherapy. And traditionally we don't focus on psychotherapy as being potentially harmful, but in this situation, it can be.

Wayne Hall: Well, psychotherapy can be too, I think. Yeah. Yeah. I think it's not so much the psychotherapy. I think, the risk here is replicating the experience of the 60s when we get an enthusiasm about the recreational non-medical use of these drugs. And if that gets out of hand in the way it arguably did in the 60s, it will put at risk the sort of therapeutic research that I think we need in order to evaluate the role that these drugs might have.

Norman Swan: So let's look at the problems that people come to psychiatrists and psychologists with which potentially could be helped here. What is treatment-resistant depression? I mean, it sounds as if we know it's depression that's resistant to treatment but what percentage of people with depression get it? Why? What do we know about it? What are they experiencing?

Colleen Loo: Yeah, so first of all, we used the word depression very loosely, like, ‘Oh, I feel depressed today and I had a bad day yesterday at the office’, that kind of thing. But, I guess firstly, we should talk about clinical depression which is at a certain threshold of illness. And there are certain definitions and defining features of that where it's more significant than just feeling a bit down which is part of normal life experience. And then a third of people with clinical depression will go on to develop what we call treatment-resistant depression. So that's where you should have first and second-line treatments haven't got you better. And the first and second-line treatments are usually things like psychological therapy, there might be lifestyle changes, and taking one or two courses of antidepressant medication. So when those kinds of things haven't worked and to remember that for the majority of people they do work, the two-thirds, then you end up with treatment-resistant depression. And then we look at what other kinds of things can we do to get you better.

And of course...

Norman Swan: Before you go on, is it always severe or it can just be your depression isn't helped? I can have depression that's not too disabling, but nothing's helping it, or is it always severe?

Colleen Loo: It's not always severe. So that's a different issue to how treatment-resistant the depression is. You can have very severe, but not so treatment-resistant depression. But the problem with treatment-resistant depression is that people get stuck and then it's all the secondary problems that arise, as you were mentioning in your life. You leave your job and then you don't have enough money and then your relationships break down because you can't relate to people and then you don't have any friends, become socially isolated and they themselves then perpetuate the depression. So that's one of the problems. It's the kind of the disability that gets associated with that. And of course people lose hope and then you also get problems of suicidality as part of that.

Norman Swan: So what's the treatment menu? What do we know works before we get to ketamine and psychedelics?

Colleen Loo: Yeah, and look, I would say the first thing, Norman, is that depression is one of those things that we all think we know what it is because it's kind of like we feel down at times. But I would say that if you think you have a treatment-resistant depression, the first thing you really need to do is go and see a psychiatrist and get a thorough evaluation because there are many different reasons why you might have treatment-resistant depression. And it's not often just is it A or B, but it might be how much of A, how much of B, how much of C, and therefore, the next step really depends on what is the evaluation of the package of things that have got you to this point and what is blocking you moving forward? Because if I had ten different people in front of me with treatment-resistant depression, what I end up recommending would be ten different packages depending on the people in front of me and their own lives, etcetera. So I think that's the first thing. And I'm not a believer in a kind of like a recipe book, first, we do A, then B, then C, then D that I think really should be based on that evaluation.

If it does look like some biological treatments would be useful, then there are options of third-line medications that are often more complex to take. They might have more side effects, require you to have dietary restrictions et cetera. There is very good magnetic brain stimulation these days- transcranial magnetic stimulation that's also funded by Medicare for your first course. But the exciting thing about treatments like ketamine and possibly psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy is that they seem to be at a completely different level of effectiveness. So things like medications, magnetic brain stimulation are at a pretty good but medium level of effectiveness. We've had for eight decades now electroconvulsive therapy, which is about twice as effective in severe and treatment-resistant depression. But for example, with ketamine, which has had a lot more development than psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, it is the first treatment to emerge really in 80 years that's been at the level of effectiveness of something like ECT.

And why there's so much excitement is that people think that, for example, psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy might be at that same level of effectiveness. But it's early days, we've got a sprinkling of evidence which suggests that it might, but we don't actually know.

Norman Swan: And when you talk about that level of effectiveness, you're talking about literally getting somebody from a state where they want to harm themselves and they're having a terrible quality of life to being in a much better place.

Colleen Loo: Yes. It's the level of effectiveness just being able to shift a very stubborn and difficult depression.

Norman Swan: When we talk, Adam, about psychedelic-assisted therapy, just talk us through how it should be done.

Colleen Loo: Yeah, I think it's important when we're talking about psychedelics here, it's not just sort of administering a psychedelic in the way we might administer standard medication. And that's a particular model in psychiatry, a patient might come in with depression, they have some psychological therapy or perhaps they have a drug therapy but really they'll be given the prescription and then they'll take that medication each day and there's not necessarily a specific framework around that. And they may not get any psychological therapy alongside it, hopefully, they do, but they might not. But with psychedelics, it's a very different model and it's in general- and this comes back from how it was done really in the 60s and 70s and really the therapy is considered important as a container, if you will, around the drug because we're talking about drugs that really alter people's experiences in a very dramatic way. So it's not the type of thing that they could just sort of take at home in an uncontrolled environment.

And essentially there's three stages. So there's what's called preparation sessions. And these typically involve educating the patient about the drug and what they might experience so that it's not something totally new when they go.

Norman Swan: But hold on a second. These three sessions are after you've had a proper psychiatric evaluation such as the one...

Adam Bayes: Of course, so you've already gone through, I guess if we're talking about treatment-resistant depression, you've had a thorough assessment by a psychiatrist and you may have tried more standard treatments initially that haven't induced a remission and then you might be eligible then and there's no family history of psychosis or personal history. So if you were deemed sort of suitable from a safety perspective, you then sit down with- it's usually two therapists, so it's not just one it's two, two therapists and have a number of different sessions to prepare the patient. And the patient might also go through what their intentions are, they want to obviously have an antidepressant effect, but it might be they might want to revisit a trauma from the past or something like that that perhaps is contributing to their current depressed state. So have some intentions going in. And they've built rapport with the therapists, okay? Then they would have...

Norman Swan: And is one of the therapists, the psychiatrist, and one psychologist or?

Adam Bayes: There's different models. I mean, that's the model that we would use but that's not essential. A lot of people ask why two therapists? Why not just one therapist? And there's a few reasons for that. One is when they actually come in for the treatment session for the day, if they're having psilocybin, it's really a full-day experience for the patient because the acute effects lasts for somewhere between six to eight hours. So really from a practical perspective, it would be very difficult for a single therapist to be in the room with a patient for that long because people need to eat and go to the bathroom. So that's a very practical perspective. But also and what's more important is the patient is in a very vulnerable state, potentially. So not only are they potentially vulnerable because of their mental illness, but also under the effects of the psychedelic, they are in an incredibly vulnerable state. And so, of course, the history...

Norman Swan: So just to explain, to have a clinical effect.

Adam Bayes: Yeah.

Norman Swan: I mean, somebody just asked about microdosing. To have a clinical effect, you've actually got to have an out-of-body psychedelic experience. I thought that was the evidence.

Adam Bayes: Probably, but I guess it's a bit unknown. I mean, we don't know that and there's hardly any studies that have been done in microdosing. So I'm talking about microdosing and having a full effect and probably to reboot the default mode network you do need that full psychedelic effect. So I was just going to say as well, you've got the two therapists in the room that act very much in a supportive role. So it's not as if they're sitting there doing Freudian psychoanalysis or something with the patient. The patient is very much they've been administered the medicine they often have an eyeshades on, there's music, there's a playlist, and they're having...

Norman Swan: It's a planned playlist.

Adam Bayes: It's a planned playlist.

Norman Swan: Yeah, I did something with Colleen recently on this with two therapists who've done a lot of this in Melbourne with people who are in distress because they've got terminal illness and people want to come and play their own genesis or whatever. No, no, it's a playlist designed to get you into...

Adam Bayes: Yeah. And the reason for that is it's thought that the music acts as a third therapist, and it's specifically designed to because the effects of the psychedelic, it takes time to kick in, if you like, and it builds until there's a so-called peak experience. And so music can kind of bring it on. And likewise, when the patients...

Norman Swan: So it's an hour or so before you get Mick Jagger.

Adam Bayes: And then you come out and the music will change and so it'll bring you out. So because psychiatry, sadly, does have a history of there's been boundary violations and things like that where a therapist has taken advantage of patients, if you have two therapists in the room, usually one male, one female, that's going to reduce the chances of that happening, though not completely, because we know that there was this study in the US where it was a trial, it was all filmed and there was boundary violations taking place in the study. But look, it's going to reduce the chances of that happening. So then the patients had the psychedelic experience, the acute effects wear off and then in the days following, usually the day after and subsequent days, there's what's called integration sessions. And this is where the acute effects have worn off but the patients really want to talk about what they experienced. And the idea is that the therapists can facilitate that and get them to make some meaning about what does it mean or this came up, what does it mean?

And are they able to process maybe some trauma or something else and then hopefully move forward?

Norman Swan: So it sounds psychoanalytic at that point rather than with the way psychotherapy has gone when is protocolized cognitive behavioral therapy, change your thinking patterns, this does not sound like cognitive behavioral therapy in the comedown after psychedelic experiences.

Wayne Hall: Well, I think a lot of the people who've been involved, particularly in the MAPS work, Rick Doblin and others in the past were fairly psychodynamically oriented. A lot of the work done in the 50s was done by people from that sort of background. And I think a psychodynamic sort of model is the one that's been adopted. I think the sort of model that's adopted in terms of the commitment of time of therapists and patients is just not scalable as a solution to very common highly prevalent.

Norman Swan: But there's no placebo. You can't do a placebo-controlled trial.

Wayne Hall: No, that's the challenge with these drugs. So that's why you should be doing comparisons of other treatments.

Norman Swan: Because if you want to get a placebo effect, this is exactly what you would do. You'd have a big shtick, you'd have music, people who believe it's going to work, the expectation it's going to work, whether it's a knee operation or whether it's this. This could be one giant placebo.

Wayne Hall: Well, I think there's probably more than that but it certainly sets up the situation for a pretty dramatic experience for a lot of people. And there's a lot of the sort of magic about the way in which it's framed. So, you're right about that. And I think if, say, the treatment for PTSD, for example, if that's going to be more widely used, then you'd expect to see more of a cognitive behavioural exposure type.

Norman Swan: Yes, that's right.

Wayne Hall: Integrated with it and probably a much shorter...

Norman Swan: This is the other treatment which is treatment-resistant post-traumatic stress disorder using ecstasy MDMA, which has got more evidence behind it than psilocybin.

Wayne Hall: Larger trials, yep.

Norman Swan: But when we approved psilocybin on the basis of a trial that showed of no benefit compared to traditional treatment.

Wayne Hall: Well, on the primary outcome, there was no difference between the SSRI, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor that was used and the psilocybin that was given in that trial.

Norman Swan: So this is our regulator that's supposed to be rigid and following evidence and has down scheduled, admittedly with a lot of guardrails around it.

Wayne Hall: Well, I think regulators earned a lot of pressure at the moment here and in the US to approve promising drugs in advance of the completion of trials because of patient demand. A lot of desperation in the case of cancer, for example, Alzheimer's disease is another example where regulators have approved the introduction of drugs in the absence of clinical trial evidence. So I think it's a more general phenomenon but I think they've jumped the gun and I think they've succumbed really to a very well-organized lobby effort to open up this sort of treatment.

Norman Swan: So, Adam, what happens after that? So you've got this integration period, you talk it through and certainly the session that Colleen and I were in with Saint Vincent's in Melbourne with people with psychological distress, terminal illness, it was very impressive what people started to talk about that they weren't talking about before and really felt better as a result. But what's the aftercare? Do you go back on an SSRI treatment or do we know how... Because it's one treatment, it's one dose?

Adam Bayes: Well, not necessarily, it could be one or it could be multiple. So it's probably more of the trials looking at multiple doses. So there might be multiple prep sessions, then a treatment session, some integration sessions, then another treatment, then another prep session, then another treatment session.

Norman Swan: But I thought the TGA had only approved one dose.

Adam Bayes: No, no, it's not necessarily restricted on the number of doses.

Norman Swan: Colleen, you're worried that this protocol might be not followed to the extent that consumers know that it should be.

Colleen Loo: Look, I think initially Norman has been so much discussion, The TGA as you say has put guardrails and you have to submit a detailed protocol to an ethics committee for their approval before the TGA approves you to prescribe. So I think initially I think it will be done fairly carefully. It's kind of the drift that happens after that that I guess you might be concerned about. So it's interesting I'm on a list server that's based in the US and some of my colleagues are running ketamine treatment clinics but one of the questions that came up one week was, we have a person with treatment-resistant depression who is receiving psilocybin therapy every week and should we stop this before we give them ketamine treatment or not? What does everyone think? Now, the way that psychedelic-assisted therapy has been presented in Australia is like it's a one-off treatment for life and almost with the implication that you have this course of one or two or three treatments and that's going to solve all these issues and that whatever you're having, depression, PTSD you will be cured.

People aren't talking about do you need to come back every three months, six months for further treatments? That really hasn't been in the public discussion at all. But from everything I've seen about treatment resistant depression and including some of our patients who've gone to have psilocybin assisted therapy, done well, for example, in the Netherlands in a proper clinic, then come back. Yes, there have been well for say, six weeks and then relapsed because the more treatment-resistant your depression, the higher the risk of relapse. A lot of these... there's a sprinkling of data. There's early studies which were done in non-treatment-resistant depression. So, when you look at the follow-up data, it looks really good. At three months, some people are well, maybe even at six months, some people are well. That's in kind of easy to treat depression, which doesn't then translate to a treatment-resistant depression group which is where we are now opening the doors in Australia.

Norman Swan: So, talk to us about ketamine and the use of ketamine and whether or not it is a psychedelic, is another matter, but it is a mind-altering substance? And what the trials have shown because you've done a lot of study of ketamine here.

Colleen Loo: Yeah, look, I've been studying ketamine for treating treatment-resistant depression since 2011, and it's about sort of 10 to 20 years ahead of psychedelic-assisted therapies as a treatment. There's probably about 10 times as much evidence of ketamine in treatment-resistant depression as psilocybin. And I think the evidence is quite consistent and quite strong that it has very powerful antidepressant effects. We know with ketamine that the effects tend to be short-lasting. So, you do often tend to need to have repeated treatments. We're not talking about a one-off course of a few treatments and then being cured. There are occasional people who might be well, but most people do require a series of treatments. And the effectiveness? So the effectiveness is, again, at that very high level of a similar kind of level to electroconvulsive therapy. That was one of the amazing things when ketamine first came out.

And in fact, I first started this research because I thought I just don't actually believe this. It's unbelievable. I was quite sceptical and I was quite astounded when I first saw this that the very first person in our clinical trial, when we got to the effective dose, was literally one day very depressed. And when I was as the blinded waiter who didn't know what he had. Doing the Depression assessment the next day was a completely different person in front of me. He was completely in remission. So, that's the other remarkable thing about ketamine. The rapid speed is not something I have seen in clinical practice. But having said that, that can also be quite challenging because is outside the realm of normal human experience, that kind of being catapulted from being severely depressed, well, it's actually quite a shock. But then of course, the other risk is you can also go the other way very quickly. So, it's actually a very complex treatment to use.

Norman Swan: So you can be better and then relapse.

Colleen Loo: You can relapse in half a day. You can go from being completely well without depression to being completely severely depressed in half a day. So, and that's...

Norman Swan: And harm yourself?

Colleen Loo: Definitely. And especially because the disappointment of that change can be. So, what we teach psychiatrists, Adam and I teach a two-day course, is that this is not something to be used lightly or without careful consideration and also a careful framework in the clinic you're operating in. And unfortunately, I think some people with the enthusiasm have set up treatment clinics without understanding all this. And people have come to grief. They've come to the clinic, done really well, really well. Everyone is happy, discharge, there's no follow-up. A month later, people are depressed and suicidal and literally making suicide attempts. That has happened and been reported with some ketamine clinics in Australia.

Norman Swan: So, describe the infrastructure you have in place, the process you have in place for the ketamine therapy.

Colleen Loo: Yeah. So, there's a few things. The first one is we look at what are your supports, including both your own personal supports as well as your professional supports before we even take you on for ketamine treatment. That's really important. Secondly, we assess you very carefully. So, you might have one or two assessments with a psychiatrist who's been specially trained up, with ketamine therapy. And we actually talk you through all of these risks. So, for example, I sometimes see people who are very depressed and suicidal, where I know that ketamine will get them better, but I talk them through that this could also be an emotional rollercoaster. You can come up very quickly, you can come down very quickly. What are the things in place when you feel suicidal? And if they're not adequate, then I'd advise them not to go ahead because you're placing them at risk. You're not doing them a favour. But these are all the things that you need to know what to assess for. We assess very carefully.

We then see people very carefully in our clinics. So, in our clinic everyone sees a psychiatrist for about half an hour before every single treatment for the first four weeks at least. And after that usually at least every second treatment.

Norman Swan: So, it's twice a week for about a month and then once a week for an indefinite period?

Colleen Loo: Yes. So, it's a very detailed treatment. But you're not talking about a simple-to-use kind of treatment. And I think that's one of the misunderstandings. People think, "Oh, this is a drug. I can just sit at my office and prescribe it and that's it. What's the big deal?" And they're not understanding that it's a very powerful drug which can do a lot of benefit. But if you don't use it well, it can do a lot of harm. And you keep people in the office for two hours? We monitor people for two hours afterwards because of the acute effects on your blood pressure, but also on some of these psychedelic effects to make sure that people are safe.

Norman Swan: So, Wayne, Adam, is there any evidence with psilocybin or MDMA that they can get that rapidity of effect?

Wayne Hall: Well, I think certainly in the MDMA case that you get these sorts of dramatic effects. I think the same of the psilocybin. And I think, as Colleen said earlier, that's why people have been interested because the more traditional treatments typically people have to take for two or three weeks before they get a therapeutic effect. But.

Norman Swan: And the risk of sudden relapse, same as ketamine?

Adam Bayes: Possibly, yeah. I mean, I guess it depends on... We don't know, I think is the answer. We don't know because there's just a lack of evidence, particularly in the area of psilocybin. I mean, we don't have. We haven't got traditionally, you'd have big phase three randomised controlled trials. We don't have that information. We don't know and certainly not with patients that have been followed up for a long period.

Norman Swan: I mean the potential here is that you get a potentially very useful therapy, but you get one or two disasters and it spoils the field.

Colleen Loo: Yeah. And just on that point, as Adam was saying, I think we don't know because there's a tiny bit of evidence. I mean, there is one study published of psilocybin-assisted therapy in treatment-resistant depression. And at the three-month follow-up, the two groups that had the high dose and the medium dose of psilocybin did on just simple numbers appear to have more people with suicidal ideation than the control group that had hardly any. Now, it's too small to be, to make anything, any conclusions. But I think it's kind of says that, ‘Gee, we don't know,’ and we need to know more about this before we go and say to everyone, ‘It's safe. That's not a problem.’

Norman Swan: Cost. So, you've just done a trial or reported on a trial that you were involved in. So, the nasal form of ketamine costs eight or $900 a dose. The out-of-pocket for your two-hour sessions, $300. So, it's anything like it's 12 or $1300 for a session, twice a week for a month then... I mean, this is a vast amount of money and we still don't really know what the cost base is going to be of psilocybin in the private sector. Some people are recording 20,000, 10,000.

Adam Bayes: Probably something like that. Yeah. 15 to 30,000 or something like that.

Wayne Hall: A lot what drives the cost is the therapist involvement.

Adam Bayes: Yeah, It's the therapist time.

Wayne Hall: You've got the packaging around it, the sorts of safety protocols. The same with the MDMA.

Adam Bayes: Two therapists at the same time. So, it's double...

Norman Swan: The thing that I'm wondering about is that, so this is sucking up a lot of person power with people with high.... Is this going to suck people out of regular psychiatry and clinical psychology for common or garden stuff that they need to be out there doing? Because there's the big bucks in psilocybin, ADHD and ketamine?

Wayne Hall: Yeah, well, I guess that's a risk.

Colleen Loo: And I think this is where we have to have careful and sensible use of resources that I don't think, like the people walking around the community with sort of entry-level depression are the people we should be treating with these therapies, which is why the two RCTs The first two trials that came out of psilocybin assisted therapy in depression didn't make sense to me because they weren't in treatment-resistant depression.

They were in the kind of people who might go to your GP and say, ‘I'm depressed.’ You might receive some something like Prozac and be completely well in four weeks. So, why give these people such a complicated and expensive therapy? It didn't actually make sense to me that they did the treatment in these, that group because I don't think it should be for that group. Whereas I think there is a place. But I think as a society we do need to find what is that place?

And given the cost and the access issues, I think it makes a lot of sense for therapy for people where nothing else has worked. But it doesn't make sense to me. And this is, I think, where with commercial clinics rolling out because, of course, if I was running a commercial clinic, I wouldn't be saying, ‘No, I don't think we should treat all of you’. There's actually many other treatments that one-tenth the cost that work. That's not. Why would I advise you that. As long as you tick the boxes for treatment-resistant depression, it might well be my assessment that, ‘Gee, if there's actually other treatments that you should try first.’ But if you tell me you wanna try psychedelic assisted therapy and you're handing over your 30,000, would our clinic management just say, ‘Fine, walk through the door’?

Adam Bayes: Yeah. And I think there's a real ethical issue as well if these treatments are only available for the wealthy and not for disadvantaged individuals in the community that have treatment-resistant depression, that's gonna, that's pretty terrible. And I should close the loop on your trial. You did the nasal spray versus the. You looked at the, sorry, the generic form, which is injectable, which is like $5 a dose, showed it was just as effective and therefore cuts out, saves you $800 a session. That's going to be another issue also in the psychedelic field. So, with ketamine that we've had generically off-patent ketamine that's been around for decades, which cost something like between five and $25 per dose. But of course, when all the evidence for ketamine started coming out, the obvious next step is for big pharmaceutical companies to develop a patented form. And when you go to the drug regulators, all you need to demonstrate is that your patented form is effective against placebo. You don't need to demonstrate it against the generic form.

So, then it gets approval. And then like in this case, now in Australia, it costs $900 per dose instead of say $5 per dose for the generic. Now, the same thing is happening with psychedelics. So, there's companies now who see this as the next big business opportunity. They're making proprietary forms of psilocybin and other psychedelics because they see this as a huge market when, as we know for example, psilocybin grows in mushrooms. So, it's, it's not like it hasn't been made up by pharma. But. And I think this is one of the controversies in the field, can it be patented? If you make your synthetic version, can that be patented and then you can charge hundreds of dollars for this or thousands of dollars?

Norman Swan: Let's go through some of the questions, some really good questions. We'll put up the lights in a minute and you can come to a microphone if you want to ask a question verbally. But there are lots here to get through. As a practitioner, is it beneficial to experience the effects of psychedelics in order to understand what your patient will go through?

This is, by the way, this is asked at every session we do on psychedelics.

Adam Bayes: Look, I mean, it's...

Norman Swan: You've just heard the answer, haven't you?

Adam Bayes: I guess as a psychiatrist, I prescribe lots of drugs to patients, anti-psychotics and antidepressants and mood stabilizers. I haven't necessarily tried them. So, that's not unusual in a way, or ECT. I've never had ECT. But I guess it's an interesting question because the subjective effects of the psychedelic seem to be so important. So, to understand that better is that important? I think it's an interesting question.

Norman Swan: Well, I mean, psychiatrists used to have to go through a full two-year psychoanalysis. Freudian psychoanalysis.

Adam Bayes: Yeah.

Norman Swan: So, that you've experienced it so that you could do the psychoanalysis. So, it's not a new thought that you should put your brain where your mind is.

Adam Bayes: I think Wayne had a... did you have a comment about this?

Wayne Hall: Well, I'm just saying that that was the historical experience that the early pioneers, Humphry Osmond and others all took psychedelic drugs, often with their patients.

They encouraged their staff and students to do it. And I think that tends to create what Mike Patton has described as sort of irrational exuberance. And there's been some of the people involved in the early trials warning about the guru temptation that people take these drugs, they become fairly inflated in their views of themselves and their importance, their wisdom. And they've got these adoring patients who reflect this back at them. And so, that's sort of one of the sort of, I guess, the hazards, the moral hazards of taking these drugs and...

Norman Swan: Which exactly fits the description of the practitioner who gets a good placebo effect.

Wayne Hall: Yes.

Norman Swan: There's nothing wrong with the placebo effect. It's just that's what you get. So, depression and anxiety have been discussed. Could psychedelics assist with ADHD? Is there any evidence on that? No evidence yet. Why is there so much resistance to think about using psychedelics recreationally when alcohol consumption is accepted? Even consequences that are widely known that's in your wheelhouse. Wayne?

Wayne Hall: Well, I guess there's a libertarian argument to be made for that. And certainly, the agenda for some people behind the medicalization of psychedelics is to open up for recreational use. And that's how medical cannabis is used, been used in the US and Canada. And so, we could easily see that. It basically created a fairly warm glow about if a drug is a medicine that can't harm you and you should be allowed to use it if you're an adult and you want to.

Norman Swan: A really good question here. And the question is but I'll expand it. How is depression and alcoholism connected and which do you treat? Do psychedelics help? So, the question. To expand on that is that 30% or 40% of people who have depression are using alcohol or other drugs possibly to, either that's caused their depression or they're using it to treat their depression. So, do we know where other substance use fits within psychedelic therapy, psychedelic-assisted therapy, ketamine therapy?

Wayne Hall: Well, I think most of the trials that have been talked about in depression have excluded people with comorbid disorders, which is one of the major limitations of them, that we don't know how these drugs will work in people who don't have simple, uncomplicated depression.

But it certainly is true that if you're wanting to use these drugs more generally, then you're gonna have to contend with the fact that a substantial proportion of people with depression and PTSD will also have problems with alcohol and other drugs.

Norman Swan: So, another question about whether or not there's gonna be more equity. In other words, what's the prospect that this could be subsidized and not so expensive? Well, I will ask you about ketamine. Ketamine is far ahead here. What's the word with ketamine? Ketamine.

Colleen Loo: Yeah. So, look, we're finding. And I work in a tertiary referral, mood disorders unit where we do see people who have failed every other available treatment in Australia, including electroconvulsive therapy. And we're finding that for these people, ketamine can be very useful. It may not get them well, but it certainly gets them better than where they would otherwise be. And so for that. But we're talking about the peak of the pyramid. We're not just talking about treatment-resistant depression, but even people at the very severe end of that.

And I think it definitely has a place. The current problem we have with scholars is that it's not publicly funded because it's a new treatment, it's not recognised by Medicare, so that, unless you have personal wealth to afford it, you can't have the treatment. That's the problem we currently have. So, one of the things that the Black Dog Institute is supporting me in doing is actually putting in an application to Medicare for an item number for the treatment process because of this careful two-hour monitoring and the careful clinic I've described does need funding to do it well. But that is a problem that we have at the moment with ketamine. And I would see that for people at that high end of treatment resistance, I think it does make sense for the government to subsidise treatment for those people. It doesn't make sense, I think, to subsidise it for people at the kind of the entry level of depression where I think even in your own interest, you'd be better off with a more standard treatment.

Norman Swan: There's a couple of questions around whether or not there's any evidence that this is good for psychological health and well-being, and that gets to the microdosing. Is there any evidence for that at all? So people using it for creativity. They feel better, it's getting to the recreational end of it.

Adam Bayes: The micro, I mean, microdosing, you know, it's been a phenomenon in Silicon Valley and places like this Steve Jobs types etc. You know, using small doses of psilocybin or LSD or whatever it might be. So sort of subthreshold doses tend, sort of 10% of a standard dose to and there's this sort of anecdotal, you know, people say, oh, you know, it helps open my mind. I can think more creatively and I can still go to work because I'm not sort of hallucinating, but there's not a lot of data out there. There's some naturalistic studies that have been done. There is though, an RCT in New South Wales, which is being carried out, though, and it's actually microdosing psilocybin, but it's for mild to moderate depression.

So there's not a lot of data out there.

Wayne Hall: Well, you talked earlier about a placebo effect, hard to discriminate between a subthreshold dose of a drug that doesn't produce any detectable effects and taking a placebo. So, I mean, I wouldn't rule it out, but I think we'd need a lot stronger evidence than the sort of anecdotal reports.

Norman Swan: So the 60s and 70s, there was this notion and I'm paraphrasing one of the questions, really, but it's a good question. The notion that if you had too much LSD, you burnt your brain out. You were just an acid head and you did it often enough. You were a write off. But the serious question lying behind that is, do we know the long term effects of clinical treatment with ketamine and psilocybin? Are we doing what's the potential for harm with long term use that's sitting behind this question?

Wayne Hall: Well, I can talk about experimental studies where people have been followed up for, I think, six to 12 months, highly selected groups of patients, they're not patients, they're experimental subjects.

And the majority of them have had prior experience with psychedelics. In that sort of setting, the number of people who have unpleasant experiences that are persistent is very small, but quite a surprising number of people, about a third have what they describe as challenging experiences. They get very anxious. They have a very unpleasant time during the session. And these are people who've had prior experience with psychedelic drugs. So of acutely people can have a pretty unpleasant time even if they are familiar with the effects. The longer term effects, we don't really know.

Norman Swan: Another question about ayahuasca. I mean, so those of you who don't know ayahuasca, this is a much more acute thing where you actually vomit and it's a sort of metabolically unpleasant experience.

Wayne Hall: Well, I think people are trialling DMT, which is the active psychedelic agent in it. I mean, I think you get sick with it because you're ingesting all sorts of plant products and other things in large quantities. And I think that sort of becomes part of the ritual of you haven't really had an experience until you've vomited into a bucket.

I don't think that's necessary. There's an interest in given the length of time that people have to be six to eight hours in a session. There's a lot of interest in shorter acting drugs, and DMT is one of those that there's an interest in.

Norman Swan: The questions are fantastic, by the way. What about people who've used psychedelics recreationally, does that exclude you from therapeutic use of psychedelics or ketamine?

Colleen Loo: It is in the research studies and it's interesting. I think one of the early pilot studies of psilocybin in depression had one person who didn't get well and that person had used I think psilocybin in something like six months before, whereas the others in that small study who had used it before had been like, many years ago. So that's also the other thing we don't know. If you've used it before, how will it affect you this time? Will you actually have the same therapeutic benefit? These are all unknown.

Norman Swan: Another question about age and I might ask about gender as well, do men benefit more than women or the other way around? And if you're older or younger, do we know those data?

Adam Bayes: I don't think we know.

Colleen Loo: I don't think we know.

Wayne Hall: Well, there's not enough people in these trials to be able to do that, to answer those questions I think.

Norman Swan: Getting the message here about the evidence base for this? Yes.

Audience member 1: Thank you. I think you've touched on this before. But and I think one of the gentlemen mentioned how involving people who had experience of this of LSD or similar drugs would be useful in treating people who need it because they're unwell. You should be aware, I'm sure, that you are aware that there are already places around the world where they use these people as support who have had experience. And I'm wondering putting that aside, that issue of what was mentioned earlier, how it may get to your head and therefore you think you're somebody special or whatever, that...

Norman Swan: You're talking about psychiatrists there rather than patients.

Audience member 1: I'm sorry.

Norman Swan: You're talking about psychiatrists there rather than patients, I take it. Sorry.

Audience member 2: I was talking about people who, if they were involved, that those people who have had drugs, they might think they've got some sort of special. So this is the guide. Yes, the guides. Yeah. I'm just wondering, wouldn't it be useful to use people who are guides who have had experience and would that be better than... And my second question is whether any one of the panel has the experience of these drugs?

Norman Swan: I think they're sidestepping that second question here. But the first one is a really good question because they're both good questions. But the first one, which is that has been traditionally what you've done is that you've had someone who's a guide who's very experienced themselves in the use of it, can detect when you're having a bad scene and can talk people through it.

Adam Bayes: Well, I think, you know, in places like Peru, you know, the ayahuasca experience and it's a non-medical setting and it's, there's a shaman and that kind of thing and his experience and guides you through and that's historically how a lot of these mind-altering substances have been used.

Norman Swan: And I think with PTSD, that veterans were going to clinics like we're not really clinics having experiences with that, with MDMA and put pressure on the veterans administration to start looking at MDMA for PTSD.

Adam Bayes: Yeah, yeah, yeah, indeed. But I think in the medical, it's a difficult area because these drugs are illegal, right? So in theory, psychiatrists and therapists can't just go out. And if they are doing that, it's potentially illegal, right? So that's a problem. But in order to, it would be possibly useful to have experienced an altered state. But there's other ways. For example, I know there's training in this thing called Holotropic Breathwork, which is where people can get into an altered state without necessarily taking a substance. And so I know that some people sort of do some training in that, so they might sort of get a sense of what might be going on subjectively for patients. Others might go overseas and do it legally. I mean, you can go to the places like Netherlands and legally experience this.

So I think there are ways, whether it's essential or not, I don't know. I don't think it's necessarily essential. It could be.

Norman Swan: I mean, it's an interesting question 'cause it could be a safety issue as well as somebody who's got experience in it, might actually. I was talking again with this one, Colleen and I did last week or the week before, I asked the therapist, who was a psychiatrist and a clinical psychologist, how many sessions before they felt comfortable. And it was a lot. I can't remember what the number was. Can you remember?

Colleen Loo: I think it was about ten people or someone like that, that they had taken through the therapy.

Norman Swan: So it's not you're not experienced after one. Yes.

Audience member 2: Yeah, I think I just have a query in terms of what is beyond for these type of treatments, beyond looking at resistant depression 'cause my partner suffers from a chronic illness and not a lot studied about it in Australia called fibromyalgia. Now, overseas they have tried using substances like this to like control it or not even control it, maybe even do some neurological repair.

Now, she had to go see a rheumatologist psychologist and he put her on like an antipsychotic to try and numb her brain activity a little. Didn't really treat the pain, didn't really treat the symptoms or anything. And I do know that now in certain states of Australia, they're treating it with medicinal marijuana and CBD, but that's more a pain thing. So I just want to know beyond the extension of looking at from depression side, will it be extended into looking at certain neurological disorders that don't seem to have a cure?

Norman Swan: I mean, it's a good question 'cause chronic pain is in the brain. It's not imaginary, but it is something going on in the brain. And therefore, in theory, something like this might have an effect. And these antiepileptic drugs and others that they're talking are being used for chronic pain are not being used as an antiepileptic, they're using to change your brain.

Colleen Loo: I mean, the first thing is that fitting in with the laws and the regulations, that kind of thing would have to be done in a clinical trial, which is in a research setting.

And so there's kind of a number of steps. And in order to set up such a trial, I mean, you need to have people with expertise, but there would also need to be able to attract substantial grant funding. So I mean, I've been doing research trials in depression and in Australia, to be frank, it's very hard to get sufficient grant funding to actually do these trials properly. You know, it's kind of roughly a ratio of one to ten, for every $10, people in the US get to do a clinical trial, we might get $1. So it's a very difficult environment. Having said that, there are clinical trials, so I don't know about that particular disorder, but you would need to find a specialist with expertise in that disorder who then has research experience, who is able to set up a clinical trial, get that funding in order to look at some of these treatments.

Norman Swan: Thank you for your question. Is there somebody at microphone three, we're probably not gonna get through everybody, but we'll try and get through quite a few.

Audience member 3: Sure. So the word guru was mentioned and in our sort of Australian culture, it has a certain stigma around it, even though in many other cultures around the world, it has a great regard, a great level of respect. We also in Australia seem to idolise sportspeople, movie stars etc rather than moral authorities or priests or people who have a lived experience of a relationship with the true nature of reality, you could call that.

Do you think that the people who have this moral authority need to be sort of elevated to a position and authorised by the fact that they can take these psychedelic substances and still sit on a stage and still present valid? What do you call that reality-tested information in a way that is relatable to people that are sort of not able to attain to that level of education and experience? Like rather than looking down on the word guru and saying these people who have what you could call megalomania are actually important parts of what it means to be human?

Norman Swan: So it's part of the same question earlier, which is that people who have lived experience and actually understand the experience that people are going through could add value. But in other parts of mental health, increasingly, you are using peer support. So not with psychedelics, but people with lived experience to help people through. I mean, this is not an out of bounds in terms of a question.

Adam Bayes: I mean, I think I'm not going to address that directly, but I'm just thinking of patients of mine, for example, that have difficulties, whether it's trauma, depression, that kind of thing. And I might engaging in psychotherapy with them for a number of years. And I've had, you know, a small number that have come in and said, look, I'm very carefully considered I'm gonna go to Peru and I wanna try ayahuasca. They've read about it. And essentially, the approach I've used is, and they've had to come off their medication because you can't sort of mix the two. And I've said, look, I don't know what I think about it. I just hope that you're safe and you do it in a very, you know, you do it in a careful environment and had one or two that have gone off and they've come back and then reported their experience to me.

And, it has been, I've learned something from what they experienced. And, in some cases it was they were able to have insight. So I think that's a sort of lived experience.

Norman Swan: And it's where a lot of this comes from, why we're talking about it. I think we can take two more. We're already well over time, but so...

Audience member 4: Yeah, thanks. Just on the note of cost and access, I guess one of the issues I see with accessibility is that, to have a therapy that's attended by a psychiatrist, a clinical psychologist, it's obviously gonna become quite expensive because of the demand that's already in place for those kinds of professionals. I'm just wondering if there might ever be the room for other paraprofessionals, like maybe mental health nurses, OTs, other workers with mental health experience to be a part of psychedelic assisted therapies?

Norman Swan: Short answer will be yes, wouldn't it?

Wayne Hall: Yeah, I mean, it would be. I think in the long run, if these approaches proved to be effective, then I think we'll see simplification, abbreviation, reduction in cost and people developing expertise that doesn't require a medical degree and postgraduate training in psychiatry.

Norman Swan: And the interesting thing that happens when you do do that is you get protocols which are rules for safety which people are more likely to follow, making the process safer, possibly more effective. So a good question. Thank you very much. And the last question. Yes.

Audience member 5: Thank you so much for your time tonight. Maybe a good question to finish on. Clearly, there's a lot of interest in psychedelic science and a lot of people in the general public would like to support and be involved in the development of further research. Clearly, we need it because there's so much we don't know. How can the general public be more involved in psychedelic science, especially here in Australia?

Norman Swan: Good question.

Wayne Hall: Well, I mean, I think we've got public funding, about 15 million that's been allocated for trials. You could probably advocate for more sort of funding of that sort. I think the worry a lot of us have is premature adoption of these treatments without that sort of evidence base. And that's when you see harm and that might damage the future research into and potential discovery of therapeutic benefits of these drugs.

Norman Swan: Thank you very much. Can I thank you all very much for coming. It's been great to have you. Really good questions. And please thank our speakers.

Applause

UNSW Centre for Ideas: Thanks for listening. This event was presented by UNSW Centre for Ideas, UNSW Science and UNSW Medicine and Health as part of National Science Week. For more information visit centreforideas.com and don’t forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Image Gallery

-

1/5

Adam Bayes

-

2/5

Colleen Loo

-

3/5

Wayne Hall

-

4/5

Norman Swan

-

5/5

Adam Bayes, Colleen Loo, Wayne Hall and Norman Swan

Adam Bayes

Dr Bayes is a clinical academic psychiatrist with a special interest in mood disorders (depressive and bipolar conditions) including their diagnosis, classification and treatment – with the latter focusing on interventional psychiatry (e.g. rapidly acting antidepressants) and novel neurostimulation (transcranial magnetic stimulation; TMS). Adam works at the interface of research and clinical application, and has an interest in developing models of care most recently establishing the BDI Ketamine Treatment Program which arose out of a clinical trial. In addition to spending half of his time managing patients as a psychiatrist, he is actively engaged in teaching and mentoring medical students, psychiatry registrars, higher degree researchers as well as contributing to treatment guidelines and conducting workshops for psychiatrists and GPs. Adam currently works at UNSW Sydney.

Colleen Loo

Colleen Loo is a psychiatrist, Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Leadership Fellow and Professor of Psychiatry at the UNSW Sydney and the Black Dog Institute. She is an internationally recognised clinical expert and researcher in the fields of electroconvulsive therapy, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, transcranial Direct Current Stimulation and ketamine, and led the first Australian RCTs of these interventions in depression. Loo is active in ECT, Neurostimulation and novel treatments research, practice and policy, providing advice to Australian government health departments, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, and several international guidelines. She has published over 300 peer reviewed papers and has received competitive grant funding from the Australian NHMRC, MRFF and major overseas grant funding agencies and directs professional training courses in ECT, TMS, tDCS and ketamine.

Wayne Hall

Wayne Hall is an Emeritus Professor at the National Centre for Youth Substance Use Research at the University of Queensland and the Queensland Alliance for Environmental Health Sciences, and a UNSW Sydney alum. He has advised the World Health Organisation on the health effects of cannabis use; the effectiveness of drug substitution treatment; the contribution of illicit drug use to the global burden of disease; and the ethical implications of genetic and neuroscience research on addiction.

Norman Swan

Norman Swan hosts ABC RN's and co-hosts Coronacast, a podcast on the coronavirus. Norman is a reporter and commentator on the ABC's 7.30, Midday, News Breakfast and Four Corners and a guest host on the Health Report on RN Breakfast. He is a past Gold Walkley winner and has won other Walkleys including one in 2020. Norman has been awarded an AM, the medal of the Australian Academy of Science, a Fellowship of the Academy of Health and Medical Sciences and an honorary MD from the University of Sydney. His book, So You Think You Know What's Good For You? was a bestseller and his latest book So You Want To Live Younger Longer? has also been on the bestseller list. Norman trained in medicine and paediatrics in Aberdeen, London and Sydney before joining the ABC.