Justice & Love

Compassion is the strongest exercise of imagination that we can think of because it’s a real attention to an absorption of another person's position.

One of the things about trying to open up the meaning of justice is to think about that suffering, the grief, the sorrow and how do you address that - that real sense of grief.

From the Paris Attacks, the Syrian War, and the European Migrant Crisis to Brexit and the US Presidential elections, our responses to others in desperate situations have been tested. Former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams and film maker and cultural philosopher, Mary Zournazi sat down with ABC’s Ethics Report host Andrew West to explore how we can experience the world in a more just way, and how does love fit into all this when we are faced with difficult times.

Transcript

Ann Mossop: Welcome to the UNSW Centre for Ideas podcast, a place to hear ideas from the world's leading thinkers and UNSW Sydney's brightest minds. I'm Ann Mossop, Director of the UNSW Centre for Ideas. The conversation you're about to hear, Justice and Love, is with the theologian Rowan Williams, UNSW Professor Mary Zournazi, and journalist Andrew West and was recorded live. We hope you enjoy it.

Andrew West: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the UNSW Centre for Ideas for tonight's event, Justice and Love. And we are celebrating tonight the launch of a very significant book called, Justice and Love by our two speakers, Dr. Mary Zournazi and Dr. Rowan Williams. Now throughout this event, we will have a live audience with our speakers and a live Q&A. So thank you to those of you who have already submitted a question. Also throughout this discussion, you can comment on Facebook. And that means you can also use the live chat on YouTube or post on Twitter, yes Twitter, using the hashtag UNSWideas. My name is Andrew West, I'm the presenter of the Religion and Ethics Report on Radio National at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

Before we start, I would like to extend and acknowledge… extend a welcome and acknowledge the Bidjigal people. They are the traditional owners of this land and we pay our respects to their Elders of yesterday, today, and indeed tomorrow. And we also extend our respect to any of our Indigenous brothers and sisters who are joining us for tonight's event.

Our speakers tonight are the authors of this book, Dr. Mary Zournazi, she's an Australian cultural philosopher. Mary is the multi award winning documentary maker, her most famous documentary, Dogs of Democracy was screened worldwide. Her most recent documentary is My Rembetika Blues. She's also the author of many books, the most notable Hope: New Philosophies for Change and Inventing Peace, which she co-authored with the German filmmaker Wim Wenders. Mary also teaches at UNSW in the School of Social Sciences. And Dr. Rowan Williams, he is the former Master of Magdalene College at Cambridge University in the UK. Rowan was most notably the Archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 to 2012. He's the author of many, many books, two of my favourites, On Augustine, and also Faith in the Public Square. Mary, welcome. Rowan, as much as I am an anglophile, I should, I'd love to refer to you by your formal title which is Baron Williams of Oystermouth because you do sit in the House of Lords. This is Australia and I know you're not someone who stands on ceremony. Welcome, Rowan.

Rowan Williams: Thank you very much.

Andrew West: Let's start, Mary, by asking you, how did this conversation, which you've now turned into a book, come about?

Mary Zournazi: I was, or have been, always have been, a great admirer of Rowan's work. And in particular, I came across his book Christ on Trial, which I found, a really important book at a particular moment in my life. It was really trying to work through questions of, I guess, forgiveness, how to think through tragedy. But one of the most interesting things about Rowan is his imagination and the role of creativity in thinking about important kinds of issues. And so I had been thinking about questions of hope, as you have noted, questions of peace. And then I had moved into thinking about justice, which came from both a kind of personal and political concern. And I contacted Rowan, and asked him whether he would be interested in working on this idea, and he agreed.

Andrew West: Rowan, this book has a lovely, almost accidental quality about it. How did it come about from your end?

Rowan Williams: Well, I’d had communication from Mary, suggesting we might get together and converse. And because I share with Mary this very strong sense that the imagination has a role to play in our morals, I was very glad to pursue this. I'd been doing a bit of work on concepts of human rights here and there. I’d been thinking through some of the ethical questions around how we define empathy, and writing lectures on that. So really, this came very timely, and it was a real stimulus to think harder. The conversations that are recorded here, took place in a variety of settings, including some rather noisy cafes where it wasn’t easy to record. But they represent, not just the two of us thinking about ideas, but also the two of us trying to respond to the unfolding world around us, in a time of colossal change and crisis.

Andrew West: I love the idea, though, that you formulated these ideas in coffee houses, all the best ideas come out of coffee houses, going back to 17th century London.

Mary Zournazi: Well, it was I mean, yeah, they were accidental in that way. But I just wanted to follow up what Rowan was saying, because it really was, we started these conversations with an idea in mind to explore justice, rights, how the imagination plays in that. And then world events kept, kind of happening, as we were, as we were working. And so we would be constantly having to deal with what's going on, Syria, Brexit, all these things. And so it became, actually, quite a concrete reflection on the themes and ideas that we were talking about, are talking about, have been talking about.

Andrew West: I want to ask you, and this is a bit unusual. How do you both disagree? It's not the usual starting point. Rowan is a world renowned theologian, a former Archbishop of Canterbury, no less, Mary, I believe you are perhaps best described as a lapsed Greek Orthodox.

Mary Zournazi: [laughs] Yes.

Andrew West: So, how do you both disagree? Because that's a good, in a way, it's an unusual, but good starting point.

Mary Zournazi: Rowan, did you want to talk? Or I'm happy to.

Rowan Williams: Why don’t you start Mary, as a lapsed Greek Orthodox.

Mary Zournazi: Okay, thank you. Yes. I think for me, it's, maybe to answer the question slightly differently is, it's about thinking about secular worlds, how secular ideas can, kind of, come to and meet theological ideas, and ways in which these two, which maybe rub against each other, actually have a potential to help us think about ways of living, ways of addressing crisis. So I guess that the point of disagreement really isn't a point of disagreement. It's actually a way of trying to reconcile different worlds, in a way, and recognizing that historically, you know, this is a moment where perhaps these things could be brought forward, recognizing all the dangers, of course, in all of that, but just that there's got to be a space for that discussion.

Rowan Williams: Yes I don't think we ever began with the idea of what we agree about and what we disagree about. We recognise from the start that we're coming from different places. I occupy a, obviously, a place within a Christian tradition, Christian community, with responsibilities that go with that. My world is shaped by those convictions, and that's not necessarily the world of other people who will, will stand with and begin with. But if I'm serious about what I believe, then I believe it's something that can be fought with, enrich and energise the conversation with whoever. So that's why I'm always grateful for the opportunity to explore where people do come from a different set of assumptions, and just see where we get, see how much of a common world we can construct as we speak together.

Andrew West: Rohan I noticed that Ben Okri, the poet who wrote the preface says that Rowan wears his faith lightly, not defensively, an Archbishop who wears his faith lightly, what do you think he means by that?

Rowan Williams: Well, I can imagine that some of my co-religionists might take that to mean that I don't take it seriously. But it does seem to me that faith is, among other things, the opposite of anxiety. So if you try to live with faith, without defensiveness, if it's real, it's deep, if it’s deep it doesn't constantly need to be dug up and crossed over and projected. You trust what faith is about, to sustain you, to give you perspective, enlightenment, courage, and all the rest, and get on with the conversation without worrying, is what I hope to say. And to say it's more unlikely doesn't necessarily mean that it's worn habitually, with conviction.

Andrew West: Mary, I guess it's, in a way, not surprising, though, that you and Rowan would have this conversation. I notice that you like to quote the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor. What did Charles Taylor, just remind us, say about the origins of values or practices that we think of as secular?

Mary Zournazi: Well, yeah, I mean, his point, I suppose, is that these have a historical origin, the move, or the words, or the ideas change historically, and perhaps where we are now with certain uses of words. They do have this meaning that resonates. And I guess, part of our conversation, or part of our exploration, has been trying to put meaning back into those words, for our own personal sense, I guess, for how we experience the world ourselves, uniquely. But how those words like love, being the obvious one, but things like compassion, things like charity, things that have kind of been well worn, I guess, but have lost a real vigour and appeal. How do we bring those things together so that they're not shied away from in discussion in people's lives, in political debate. And I think we could probably say there's, there's a real vacuum of those kinds of deeper senses of meaning in political debate. I'm not saying that everything is like that, but the need to sort of, in fact, enact the practice of taking care and so on and so forth, I think are things that theology and secularism could come together more profoundly. Yeah.

Andrew West: But Rowan, I'm reading…

Rowan Wiliams: One other thing.

Andrew West: Oh yes, I’m sorry, go on.

Rowan Williams: But just to add to that, one of the things that Charles Taylor really put forward is, what's happened to our concept of the self in the modern centuries. The, if you like, the exposure of the modern self, were left as it were, to make it all up from our own bowels. As if we have to make meanings as individuals, without resource, without nourishment, without guidance and community and relations. And whatever else through religious discourse, it says your self is always plugged into networks, resources, screens of life and meaning that you don't fully grasp. You have to let yourself be faithful, not just think it all depends on you. I think what Mary's talking about is how we, how we keep alive and re-vivify that sense of belonging within something that's not just about our preferences, our feelings. To fill out the world, and fill out the self too.

Andrew West: Now, the book, my well, notated copy here, is titled, Justice and Love. These terms might seem blindingly obvious, but I think you actually have a discussion about what they mean. And you both have a very nuanced view about what justice means. We'll deal first of all with justice. Rowan, and how do you define justice? Because it's not simply the scales of justice. It's not simply the legal notions, is it?

Rowan Williams: Very much, very much not. I start really from the position that we think of justice primarily as making sure everybody gets what they deserve. But when you look at classical philosophy, or the Bible, what you see, and what the very words in Hebrew and Greek is, justice as a sense of being alive with something, being in tune with something. Just like, if expressed in the phrase we still use, doing justice. Does that performance injustice remove the work? Is it really in tune with what's going on? And that sense of justice as attunement, alignment, being in harmony with what is there and thus being in harmony with other people, so you do indeed react in an appropriate and just way. I think, unless you have that deep understanding, your notion of justice will be very diminished. I guess that's what I most wanted to push to in regards to justice.

Andrew West: And what do you say is the problem Rowan, with an outlook that says that justice is just about getting things settled. I don't mean necessarily getting them settled and out of the way. But what is the problem with the idea of reaching a final settlement in justice?

Rowan Williams: There's something to be said for the idea of settlement, simply because you need, often, an agreement about the basis on which we proceed to act and go forward. But the notion of settlement might suggest there's a bundle of requirements, entitlement and so forth, which have to be met before you can move forward, that everyone comes into the world with a bundle of entitlements. And that's not, in my mind, the most important thing about human rights, I think there's something deeper and more demanding. And there has to be somewhere a sense that we will never completely do justice to one another. We're always struggling to attune ourselves in understanding and learning in our relation with others, so that there's a dynamic and creative quality to justice. If you talk too much about settlements it might diminish that.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, I guess, one of the things for me was trying to think about when it fails, you know, and, and often it fails for people, because it's settled, and maybe it really wasn't settled. The issues, the grief, the sorrow, and I think, you know, one of the things about trying to open up the meaning of justice, is to think about that suffering, that grief, the sorrow and how do you, kind of, address that, that real sense of grief? Which I think, you know, underpinning a lot of people's displacement, a lot of people's anger, is a grief, you know, is some fundamental grief that's not addressed. And I think you need to complicate justice in that way. So of course, you know, legal, you need the legal world, of course, but you also need to have an openness towards trying to explore possibilities of how do you deal with somebody else's suffering? And I think Simone Weil is a philosopher that both Rowan and I do really like, I think she offers some interesting ways to think about the harm, the cry, you know, how do you address that? How do you actually address somebody else's suffering without diminishing it?

Andrew West: Mary, you also come up with this idea that justice involves the right to refuse.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah.

Andrew West: Which I found a fascinating concept. Flesh that out. What do you mean by right to refuse?

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, I think it's borrowed, actually, from Simone Weil, who writes about the power to refuse. And what she's saying, if you are in a culture, wherever that be, and you don't have the power to actually say no to something, then that is actually saying something about the social order in which you're existing. So if you can't say no to being exploited, then there is something that has to be addressed in the social order to the reason why you don't have that power to refuse. That power to say no to an injustice, I think, to have the power to say no to something is a position that very few people really have. And I think it's something that she's presenting. And it's something I think that's really important to think about. That, if you are in a situation where you can't say no to it, and you're being forced to continually be exploited, then that's taking away your power, that's taking away your agency. Does that help? I hope that helps.

Andrew West: No, it helps, it helps a lot. It raises for me this other question, too, that I'd be interested in Rowan's perspective on. And that is, the question of justice, as administered by those in authority. Now, is every law that is promulgated, if you like, by a justly or properly constituted government, that is a democracy, is that required in a moral sense to be followed? As opposed to laws that may be promulgated by a dictatorship, or even worse, a totalitarian government?

Rowan Williams: That touches, doesn't it, on the distinction between what is lawful and what is right? I think that just because something is lawful doesn't necessarily mean that it is morally right, good, or bad in itself. But it tells us there is a broad moral agreement of something in society which is reasonable to go along with. So ordinary, what I call routine law, is certainly a moral matter. It doesn't in itself tell you what the good to be pursued is. And this is something we often get a bit muddled about. We think that perhaps when we've settled a legal question, we've settled the moral question. And that's not necessarily the case. Or we want, because we feel strongly morally about something, we want it legally enshrined. And I have some worries about that. I like the idea that a good society keeps on having moral arguments, even when it comes to settling certain questions. To take the obvious route, lots of religious communities continue to have real, moral discussions on abortion, conditions on whether that ought to be legal, and many communities want to enshrine their position as law. The legal position is that this is permissive. So, I don't think that a religious community ought to be struggling to enforce its position in law, but I think the argument can still be had, the moral argument. So it's a complex area. But I just want to pick up, also, what Mary was saying about the right to refuse. What we're talking about there is, just involving a recognition that the other has a voice, and that what you owe to them is not just the set of debts, owe them their freedom, you owe them their freedom of speech. If you are getting in the way of that freedom to act, to contribute to society, then that is an unjust situation. You have to try to release the voice into action, into engagements, into arguments.

Andrew West: You both quote, in the book you like, the great 20th century theologian and indeed, Marta, Reinhold Niebuhr. No, I'm sorry, Rowan, just remind me, his statue is atop the 20th century martyrs at Westminster Abbey, not Reinhold Niebuhr, as great as he was…

Rowan Williams: Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Andrew West: Dietrich Bonhoeffer, you both invoked Dietrich Bonhoeffer. I mean, Bonhoeffer was someone who very definitely spoke about the right to refuse, and that was, that you needed to put a spoke in the wheel of power.

Mary Zournazi: Well, I think Rowan's probably more the Bonhoeffer, kind of expert here, I'd say. Yeah. Did you want to?

Rowan Williams: No, not an expert, but I’ve got a lot of enthusiasm. And part of what I find so deeply fascinating about Bonhoeffer is precisely that he addresses some of these questions about what do we owe to government? He’s got quite a strong sense that good government does commonly require our loyalty, our commitment, but that it deals with what he calls the penultimate of the ultimate. When government tries to settle ultimate questions of human identity and human need, in a way, which also excludes other human beings, then you've got a problem, you've got a call to resistance. So if you have a government that seeks to make loyalty to itself for one test of citizenship, if you have a government that systematically dehumanises other groups, especially the Jews in Germany, then that government has lost its faith to be just. The paradox is that really good government is government that knows its limitations.

Andrew West: We've been talking, theoretically, in the second half of this discussion, we're going to talk in very concrete terms, but rather than aggregate all the questions from the audience to the end, I'm going to ask some now to kind of break this up. We have a question, from, we have a very important, very basic question, powerful, in its simplicity, from Monique Dam. What is the role of compassion? I'll start with you, Mary.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, it's a great question.

Andrew West: As I say, powerful in its simplicity.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, I mean, I think, to sort of come come to it in a roundabout way is, I think, the issue of love that we've been discussing and grappling with and thinking through, you know, an element of that is compassion, you know, the ability to, I guess, feel and understand another. But I think, love itself in which compassion also fits, I think is a bigger term. And I have to say, I was listening… just recently I've been re-listening to David Bowie and Queen and, Under Pressure. And there's a wonderful line that they say to the extent that you know, that love dares you. You know, love’s a dare. And I think if you think about it in that kind of really interesting way, it's not anything boring or weak or insensitive. Compassion is strong and powerful, and in fact, has a real strength that we haven't even tapped into yet. Because we almost feel like it's just something that's, oh yeah. But it actually has a real force and a real dare. And I think also creatively, if you think of the best art, the best stories, there is always that dare. And I think love and compassion bring us that, in a sense.

Andrew West: Rowan?

Rowan Williams: It takes us right back to where we started, I think, with the role of the imagination. Compassion is the strongest exercise of imagination that we could think of, because it's a real tension to an absorption of another person's position, another person's, I wouldn't say taking their emotion, but a real sense of what it is like to be there. And to see the world from a perspective, that is not dictated by my preferences, my concerns, my feelings. So compassion is a freedom, which is why it is indeed, a central strand in love. It's a freedom to be there with and for another. And represents not the kind of flabby, oh I know, response to somebody else's suffering, but a real commitment to solidarity, presence.

Mary Zournazi: Can I just follow that?

Andrew West: Please.

Mary Zournazi: Can I follow that Rowan? Because one of the things that struck me in conversation with Rowan, because I mean, it was just a gift to be able to discuss these ideas, you know, with you. You had a line, which I loved very much about the need to train the imagination. And I think, in that sense, too, we need training. And when we need to learn what compassion is, it's not just like, all of a sudden you have it. You know, it's something about it being an art in itself of learning, or of unlearning cultural habits. And, and that's where I think, you know, education, all these things become really vital, because, and public discourse, public discussion, in how to train the imagination.

Andrew West: Let's stick with Rowan. And a question from Ann Clifford, if we are called, and this is, I think, particularly apposite for Rowan. And if we are called to love those who do not love us, does justice provide a framework for how far we should go in our love?

Rowan Williams: That's a very good question and a very, very searching one. So, let's see. If we're called to… let's put it this way, to be faithful to one another, to stay with one another, that's I would say, the basis of a really moral pursuit, the recognition that the other person is not going to go away. And I have to come to terms with, that doesn't mean I don’t challenge, and it doesn't mean that I don't say to the other person, I don't think you seem clear. We argue, I think this is, as I hinted before, this is an important part of what a working society really looks like. We have the freedom to argue, without anger and without violence. But it's hard work. We would all like things to come quickly where we say that’s it and someone else will feel the same. And that won't happen in a hurry. Why I say we need faith, we need to recognise that the other is not going away, so I need to hold my ground and keep on with that loving, attentive, but also truthful and integrity for it. So justice helps as an idea, simply in saying, I need to try and see and hear the other person without the distortion of my own fears or worries. I need to try, with the other to find a way of seeing the world around that’s consistent and sustainable, and we work together as best we can. I’m not saying, are not saying that this is a magic bullet.

Andrew West: Ann’s question is a very good segue into the next section of our discussion. I want to now talk in concrete terms. We've been talking in very philosophical terms about justice and love. I want to ask you both now about the ways in which the last seven or eight years since you began this conversation, which I think began in 2014, 2015. I want to ask you about the ways in which love and justice have been tested by current events, ongoing events that convulsed the world, Mary? Terrorism, surely the most significant test of the concepts of love and justice?

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, I'm trying to find a way to think about that, as well as to think about the effects of it, because I'm, can I talk about Syria for a moment?

Andrew West: You most certainly can talk about Syria.

Mary Zournazi: Because I think one of the one of the things that really did emerge when we were having our discussions, was Syria. And I think one of the most devastating things, I think, is the civil war there, which I think is a result of a lot of, you know, historical issues. But the effects are on everyday people. And how do you respond to that? How can you respond to that? And I think there is something really significant about — and I think Rowan talks about this a little bit too, in our discussions — but just the basic, kind of, humanity, of welcoming somebody, of recognising them in some particular kind of way. Recognising the context in which people who are perhaps drawn to a certain violence, are coming from as well. So that it's not just I mean, it’s role also of understanding the oppressor and the oppressed, at the same time, trying to understand what is driving certain kinds of violence. And I think, Rowan, you said something too, really, that I like very much, that there's nothing automatic about violence, there's nothing automatic about it. It doesn't have to always happen, you know? And so I think one of the challenges for us, and I think, in real terms, in general, is yeah, how do you, how do you address the other? The person in front of you, you know, who is suffering, the effects of bombs, war, whatever it might be, you know? And that could be the person who's actually throwing the bomb as well. So it's kind of, I guess, it's in no way excusing acts of violence, but it's trying to find ways to understand, I guess, the destitution of people and others.

Andrew West: Syria was the classic wicked problem, though. I know that Rowan through Christian Aid has paid a lot of attention to the crisis in Syria. It was the classic wicked. problem in this sense that it was or is a country held together in a very fragile way, balancing a whole lot of different religious confessions, the fear that religious minorities had, of being not simply oppressed, but even eliminated by an angry, resentful, long suppressed religious majority. I mean, that was a classic example wasn't it Rowan, of really, justice that was, we were searching for a kind of justice there, that was almost impossible to clarify, if you get my point?

Rowan Williams: Yes I do. I think what I was hearing quite often from people in the region was, people are trying to solve our problems from outside, without attending, once again, to the complexity of common law relations on the ground, are consistently making it worse. Now, we've had, I think, decades of this attempt to impose various kinds of grid, settlement, pacifist occupation in the region, most of which have not arisen out of any real sense of others in the community working together. And that's, that's the tenure we're currently in. I just don't myself think that piling on the pressure, military or otherwise, on the region actually makes it less of a pressure cooker, because, by definition, we're not liberating, we're not releasing. Now, that's not to say, obviously, echoing Mary, not to say that we can weakening on the condemnation of violent action, indiscriminate terror and murder. Clearly these need to be resisted, these need to be avoided and sometimes, sometimes, yes, force is needed, but we have indiscriminate language of solutions that can be imposed from the outside. So, yes, it is a complex problem and as Mary says, we need all the time to go back to the present. What is it that makes terrorism look like an appealing option? What is it that makes it credible? That requires a big leap of imagination. It's not to collude, it's not to condone. Simply to say, we need to understand where this comes from, only then do we have a chance to creatively respond.

Andrew West: Mary, you can answer your own question for me here, the one that you pose in the book where you say, what are the implications? Because it's a perfect example, Syria, what are the implications of selfishly oriented or ruthless decisions on people? What did Syria tell us about that, about that issue?

Mary Zournazi: It told us that, I think, we need to really address that, kind of, ruthlessness because bearing in mind the complexity, and I guess, also, can I just say, having just been to the Middle East, and particularly Egypt, as looking at the historical structure of a country, which has been colonised over and over again, and the effects of colonisation, also colonialism on countries, it's like, way back these histories, and also until we take some responsibility, not to say that we are condemned to, you know, our own, you know, that we blame ourselves for what happened in the past, but we are responsible to it. And I think Emmanuel Levinas has a wonderful line about it, borrowed from Dostoevsky, that we are responsible for people that came before us, and we have to deal with that responsibility now. So in other words, even though we may not have caused the violence directly, we have to in some way, embrace it and try to address it. And that's not easy. I mean, there's anger always on every side, you know, why should I help somebody? Or why should they give me gifts, or whatever it might be. And I think there's something in that recognition. And also, when you see people I must, I was in Lesbos, where the Syrians were arriving at the time. And you see these boats, and you see, you see the debris, and you realise that, you know, there's like a Snow White backpack, and you realise that that whole family has just drowned. And you know, you think, oh, they don't, you know, you don't realise that commonality, that kind of sharedness, that humaneness that we have, but it's not only human, I think Rowan and I were also talking about, you know, non human, you know, sentientcy,, the whole thing about trying to understand our responsibility to a certain degree, is that realm of justice and love, a long way of answering that question.

Andrew West: But broadening it now to the, to the broader question of terrorism, political violence, Rowan, and you have this wonderful quote, where you talk about the different ways in which people are characterised, they're characterised diabolically, which I assume, also, you know, relates to diablo, the devil. They’re characterised diabolically, they're characterised humanly, or they characterised angelically. Tell us about that concept, and how it relates to political violence because someone's diablo is another person's saint really, isn't it?

Rowan Williams: Yes, the origin of the quote is in a remark made by a Christian teacher of the late fourth, early fifth century, where he talks about the three different ways in which we can look at the world with an ordinary human knowledge, which, as it were, just register what’s there, with a diabolical inch, which tries to turn everything into raw material for my needs, my priorities. The angelic, which sees things as they’re turned towards God, sees things in the true dimension. So it's really about my attitudes and responses to the world, do I see the world in terms of my agenda? Or do I look at the world as turned away from me towards something deeper? And that sense of looking at the world and forgiving other people, but also importantly, including the natural order, relating to something other than just my priority, that's the beginning of wisdom. Now, in political and international affairs, naturally, we begin from that self oriented perspective. How does this affect me, how does this serve me and my needs? What if we were capable, a little bit more of saying, well, let's look at another country, another person, in their own terms, let's listen a bit and learn something with their own language, see what their priorities, and so on, are. And it may be that we will find that along serving and identifying with those needs gives us more security or more stability than simply trying to impose our own agenda.

Andrew West: See – this point to both of you – in the circumstances of mass political violence, dispossession, we're tempted to see but we're tempted to see one side or, look, put it this way, people see the terrorist as either the devil, as either the incarnation of all evil, or they see the terrorist as someone divinely ordained in their behaviour. So they see the terrorist, diabolically or angelically. The toughest thing surely is seeing the terrorist humanly, seeing the terrorist as someone who might be us in a certain circumstance.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, and I think we talked about a little bit in the book, there's a film which I, you know, I'd recommend actually called Paradise Now, which is about two Palestinian suicide bombers. And you realise the context in which they're coming from, and they are very human. They're doing it as an act in that sense for a particular conviction. It doesn't, it doesn't necessarily make it right. But you come to understand, you know, they come from families, loving families, you know, but they come from destitution as well. So it's, it's trying, it's trying to understand, I think that's the point Rowan's making too, it's trying to understand the context in which this violence emerges. And I think that's where justice has a role. And that's where love has a role. Love not in… I think it's redefining the term, you know, making it bigger, broader. And I think also, Rowan said something about, you know, turning the other cheek is not is not a passive act. It's actually an act of action, in a sense, it's about taking a movement. I always found that really fascinating when we were talking too, your thoughts on that, on that notion of its action.

Rowan Williams: Yes, it's a very challenging idea, I think, that turning the other cheek was not simply accepting violence, it's the kind of refusal, active refusal to collude with violence. It's saying, I'm not going to play that game. Let's change the terms of this encounter. Now, that may or may not work, for people, it's certainly something that people have to have to sense as a real, personal, challenging calling. But I think it is extremely important to get across the idea that peacemaking is itself active, not passive, not just the cancelling of violence, but the active engagement with the reality that’s there. And going back to what you were saying about a terrorist. I think the other film that I mentioned in the conversation was the British film Four Lions. It's about four very vulnerable, muddled and confused Muslims in Britain, who get sucked into a terrorist group. And they’re hapless and confused, and it doesn't in the least, justify or make sense, moral sense, of what they get involved with. But you begin to see them also as victims. And when you begin to see the other person as, in some sense a victim, not just someone who's, if you like, the source of meaningless, barbaric behaviour, you begin to see something of the humanity, not condoning that said, again, not softening the evil, the appalling terror, but to say some of those caught up, are precisely caught up. They're sucked in, they’re vulnerable, they're exploited by others and that's part of the difficult recognition.

Andrew West: Let's move on now. And because we don't have a great deal of time left, I want to talk about nationalism and tribalism. Because, boy, if there's, you know, two phenomena that have convulsed the world in the past five or six years, it's been those two. Rowan, and you have this wonderful line about the notion of identity. And you say that the good identity is one that enriches the stranger. What do you mean by that?

Rowan Wiliams: If I feel that I'm deeply rooted in who I am, and where I am, grateful for, and conscious of a tradition, which I want to share, for the well being, the flourishing, the enlargement of someone else, I think that's, that's a healthy way of inhabiting a tradition and identity, and nationality. If I approach my relations with others, always thinking, the others' very presence threatens who I am, then I end up building thicker and thicker walls around my own identity, so that it actually shrinks, it becomes less secure, and what takes up the spaces is the wall. Well, that's the difference I’m trying to get at.

Andrew West: Mary, enriching the stranger with your own identity. How would you achieve that?

Mary Zournazi: I like, I think this is, this is part of the religious tradition. And I think it's part of something, I think that Jesus or the Christian tradition is, you know, inviting the stranger into your house, you know, actually having… like, come, come in, have some food, come and share with me. Because what we've lost is that sense of the stranger, that it's a welcome, it's a real welcome. You know, it's not… and it's in that welcome, or in that hospitality, even though there's a lot of argument around the difficulty of hospitality because of who's been, you know, who's being the host, so on and so forth. But I still think there's something very rich in, you know, welcoming, in actually the stranger coming into your house in that sense.

Andrew West: But I'm not saying this is a legitimate feeling. But it's an understandable feeling. A lot of people think the stranger is there to do them harm.

Mary Zournazi: Well, yeah, that's, that's, I think, the common sort of myth, right? And I think that's also to do…

Andrew West: I mean, if you're, if you're a German woman in Berlin, and someone sets off a bomb, or has a terrorist attack in a Christmas market, it’s not a myth.

Mary Zournazi: Well, I was there, actually, and one of the most interesting things I found was that the whole wall where that had happened, everybody had the need for peace, the need for love, at that moment, the response was that, we do not want to have more violence. We do not want more of this. And the letters that were on the walls. I mean, it was just something to actually behold in that sense. But yeah, of course, there's that anger, there's no, there's no… there's anger there, but to dismiss… to even open up the possibility of sharing, you know, to break down those barriers, those borders are crucial. I mean, yeah, I mean…

Andrew West: On a more benign level, in your country, Rowan. The notion of identity became very complex during the Brexit debate and subsequent because a lot of people there simply didn't think they had the same identity, not just talking about ethnic identity or religious identity, they simply didn't think they have the same national identity as their neighbours, did they?

Rowan Williams: You're quite right. That was one of the deepest issues in the Brexit debate that suddenly, we discovered how divided we were as a country. How much great swathes they felt they've been abandoned, and neglected by a powerful elite. And although I voted against Brexit, I feel there's an ongoing and still unfinished agenda around how we reconnect deprived and declining communities, with the practice of government and with, again, a just society in the broader sense that allows people to feel they have a say, they have a presence. It's of course reflected in a growing in regional power, regional hubs, talking about large cities of the north, acquire more, more self determining powers, it's reflected in, of course, pretty dramatically the growth of Scottish separatism, even in Wales where I now live, in return.

Andrew West: Oh, you're not going to split off. Please don't tell us that.

Rowan Williams: Well watch this space. I doubt it, but there’s certainly a resurgence of Welsh nationalism. Yeah. And all of that reflects the sense that we have a governing that is not plugged in to the needs and concerns of local communities. Now, if you have certain kinds of political leadership, most obviously, Donald Trump in the United States, you can even exploit and weaponise that sense of alienation, the most dramatic and indeed toxic ways possible. But if you're going to avoid that exploitation, then you need to do some very hard work about how governing groups are more deeply connected with the decision making of local communities, have also to foster the decision making structures that are available in local communities, and make sure that they're embedded in one another, that they lock together. And there's a lot to be done in renewing democracy.

Andrew West: Mary, just as we wind up. The other thing that, sort of, hangs over this book, as you put it together last year, is of course, the pandemic. There's a lot in your book about the idea of the commodification of the person by economic systems. I want you to answer a question that Rowan poses, because I think it's so appropriate to the pandemic and all the sacrifice that it has entailed, who's lost their jobs, whose business, whose little corner store has gone out of business, while everyone migrates their money to platforms like Amazon. Rowan poses this question, who pays the most when things are difficult? Who has paid the most in this pandemic?

Mary Zournazi: Well, yeah, I think, I think, I think everyone has, in different ways.

Andrew West: Really? I mean, some people have been enriched by the pandemic.

Mary Zournazi: In different, well, I mean, the everyday person, perhaps, that’s probably a better way of putting it. I mean, I'm thinking more about, you know, walking down the street. I mean, even today, I go to a chemist to, you know, pick up certain things, and the guy that's owned the chemist has just left now, because he can't afford, because of the pandemic, you know, so the chemistry is gutted. And I guess, for me, it was sort of like these everyday things that you expect to be the same, have changed. And it's often to do with, you know, the, sort of, inability to keep up. And I guess, when I say the everyday person, I guess I mean, that for a lot of us at the moment, we don't know what's going to happen. We still don't know how this is unfolding. But we do have a lot of grief, I think, a lot of us in different ways, whatever that might be. And I think a lot of people, I think it gets more complex for people also who have never really handled society that well anyway. And so all of a sudden you have these measures about distancing or not being able to see people, and so the despair, I think, is hitting the everyday person in that sense. So I think, yeah, a lot of people can exploit it. I think Yanis Varoufakis said something really wonderful, you know, that Amazon has become like the new Red Cross or something, you know, but actually, it's making a lot of money out of people, right? So it's the shifting parameters of what we view as I guess, kind of value and worth, you know, has moved more towards, I guess, the commodity, or the commodification of things. But the real value, I think, is in the recognition of our everyday experience, which I think, this is where I think love and justice kind of come into play, that recognition.

Andrew West: Yeah, final question. Before we take some questions from the audience row and answer your own question, who pays the most when things get difficult?

Rowan Williams: One of the things we've learned in the last year, I think, is that there is, what I'd call, a front line. Care workers, people with vulnerable mental health conditions, minority ethnic communities, all of these seem to be disproportionately carrying the load. And just to become aware that there is a front line, there is a category and society of people who will be the first to suffer. That's an important recognition, because if that's the case, we need to make sure that the protections and support are there for those who are on that front. Whether it's coworkers, health workers, people with mental health conditions, people in minority ethnic communities and so on. So that's one thing I hope we may have learned about, because those seem to be where the burdens really land. But Mary’s also importantly said, we've discovered that in certain circumstances, we're all prepared to pay a certain price for collective safety, collective health. But we're not perhaps as selfish as some might appear.

Andrew West: Let's use the last five or six minutes to take some questions. Do we have any questions? Do we have any questions? We don't have any questions from the audience? Well, let's pick up a couple more of those very thoughtful questions that were sent to us earlier. Kevin O'Sullivan, vitriol is the new language of division, especially via online social communication, what is the antidote to return to more life giving and respectful dialogue, as we listen deeply to one another, despite our differences? Marry?

Mary Zournazi: Yeah, that's also a very big question.

Andrew West: Well, and it’s the question for our time, really.

Mary Zournazi: Yeah. Yeah, I think I mean, I guess one of the things that we've been trying to investigate too, is how to give meaning back to, to words, to what you say, in a sense, how you say it, that there's an integrity or a dignity given, an understanding given. I think the problem perhaps with Well, the good thing about social media in the sense is that it can actually circulate information and people can get it sort of instantly. I think the problem is that we don't spend enough time really taking time to hear, to listen, to take time, to be patient, and to care for that interaction. So the speed of things, I think there's one also key thing that we discussed is time, the need for attention and time, like taking time. Time has probably been the biggest exploiter in the last 20 years, I think. And I think social media kind of accelerates that. But then it is also a platform for ideas. So you know, it's a balance, but I think bringing time back into the equation, taking time before you, you know, spit something out. It's probably a good thing.

Andrew West: Rowan, this is from Saba Shar. What are the practical things that I can do to bring more love and justice to the world, to those who need it most?

Rowan WIlliams: It starts locally, I think, look at the community you’re in, and ask who are the people most likely to feel forgotten? What would make those people feel less forgotten? And that may be a category of people, it may be a community, it may be a particular neighbour, it may be a member of your own family. But that's, I think, where you start, just look around and step back enough to see who is not actually represented, audible, visible here? And what can I do to include their voice, their perspective? And on top of that, I think, thinking about what Mary has just said, maybe look at your own daily rhythm and your own pattern of life and say, how do I give myself time to be, and to be free from the hectic, feverish needs? To get my presence, my views etc. out there? How do I step back from myself and breathe and be and see that more clearly?

Andrew West: That's a wonderful place to end, Rowan and a terrific question from Saba to end on. It's been a terrific hour with all of you here. I just want to now recommend this marvellous book, Justice and Love: A Philosophical Dialogue. Mary Zournazi and Rowan Williams. And I want to thank Mary and Rowan. It's been a challenge on a difficult zoom line for Rowan, but it's been a pleasure to have you Rowan. Mary, thank you very much. I also want to thank the UNSW Centre for Ideas. It is the incubator of so many great public discussions in this city and this country. I want to thank them for the work that they've done again, under very difficult circumstances, in putting this together. Thank you to those of you who've been able to be here. And thank you to the many hundreds of you who've been joining us online. Thank you very much. Good evening.

Mary Zournazi: Thank you, everyone.

Ann Mossop: Thanks for listening. For more information visit centreforideas.com, and don't forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

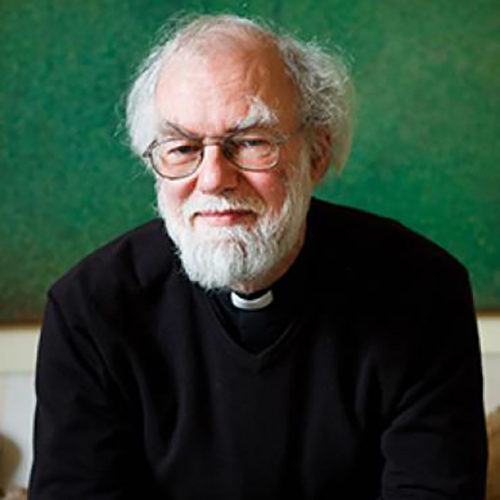

Rowan Williams

Rowan Williams (Baron Williams of Oystermouth) is former Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge (UK). He was formerly Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity at the University of Oxford (UK) and was Archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 – 2012. Rowan recently co-authored with Mary Zournazi, Justice and Love – a philosophical dialogue.

Mary Zournazi

Mary Zournazi is an Australian film maker and cultural philosopher. Her multi-awarding winning documentary Dogs of Democracy was screened worldwide, and her most recent documentary film, My Rembetika Blues is a story about love, life and music. She is the author of several books including Hope – New Philosophies for Change, Inventing Peace with the German filmmaker Wim Wenders, and her most recent book is Justice and Love – a philosophical dialogue with Rowan Williams. She teaches in the sociology and anthropology program at UNSW Sydney in the School of Social Sciences.

Photo credit Effy Alexakis.