Elevating health in the climate debate

It's an incredible thing that there's now a team of 15 of us who are sitting there thinking every day, like, how do we make our health system net zero?

As we grapple with the increasing consequences of climate change, experts are warning that it’s not just an environmental issue, declaring it the ‘biggest global health threat of the 21st century’.

In the face of these warnings, where does Australia stand in its preparedness to address these health challenges, both locally and globally?

In a discussion led by ABC’s climate and health reporter, Tegan Taylor, hear from experts on how disasters such as bushfires and droughts, which are heightened by climate change, are triggering a spectrum of health risks - from infectious diseases to respiratory issues, and mental health challenges - with the vulnerable minority and at-risk groups bearing a disproportionate burden.

Transcript

UNSW Centre for Ideas

UNSW Centre for Ideas.

Adrienne Torda

Hi everybody. I'm Adrienne Torda, Interim Dean of the UNSW Faculty of Medicine and Health, and it's my absolute pleasure to warmly welcome you to tonight's discussion on the critical intersection of climate change and human health. I'm delighted to see many familiar faces, including my primary school best friend, here this evening. Your presence underscores our collective commitment to addressing the profound health impacts of climate change.

So thank you, everyone for joining us. I'd like to begin by showing my respects and acknowledging the traditional owners, the people, the traditional owners of the land on which we're meeting tonight. I'd also like to pay my respects to the elders, both past and present, and extend that respect to other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who are present here tonight.

Climate change poses a fundamental threat to human health, disrupting not only our physical environment, but also societal and economic structures, including healthcare systems. We're witnessing an alarming increase in the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, directly impacting human health, and having a major impact on the healthcare infrastructure. In 2023, Australia faced record breaking temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns, leading to devastating consequences for numerous communities spanning from bushfires to floods.

These events highlight just some of the immediate and profound implications of climatic events on health, particularly for vulnerable groups such as socio-economically disadvantaged communities, rural areas and Indigenous populations. The interconnected nature of environmental challenges underscores the need for attention and action. Despite progress in national planning, there remains a significant gap in adaptation efforts moving forward. Implementing and scaling up these plans is essential but presents formidable challenges.

Tonight we will confront and discuss a number of these issues head on, examining some of the health and possibly also social issues that we now face as a result of environmental change. Together, we must explore solutions and discuss potential actions to support and protect the health and wellbeing of current and future generations. So it is now my pleasure to introduce our panellists and host, firstly, Tegan Taylor, the moderator of tonight's panel.

Teagan is a multi-award-winning health and science reporter for the ABC. She hosts shows including Radio National's Health Report, Quick Smart and What's That Rash? She's received a Walkley Award, the Eureka Prize for science journalism, and her work has appeared in The Best of Australian Science Writing.

Doctor Georgia Behrens is the Assistant Director of the National Health Sustainability Climate Unit in the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, having been instrumental in writing the National Health and Climate Strategy, which was launched in December 2023. She has worked in numerous advocacy, research and policy roles across climate and health disciplines. Georgia trained and worked in clinical medicine before completing a Master of Science, Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. As a General Sir John Monash Scholar.

Scientia Professor Guy Marks AO is a physician and epidemiologist at Woolcock and UNSW Medicine and Health. Guy's background is in respiratory medicine, public health and epidemiology. Guy served as the president of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases since 2019 at Liverpool Hospital. His clinical practice involves managing individuals with TB, both clinically and from a public health perspective. His research, conducted in both Australia and Vietnam, centres on public health strategies to combat TB and the health impacts of air pollution, focusing on ensuring clean air and addressing chronic respiratory conditions.

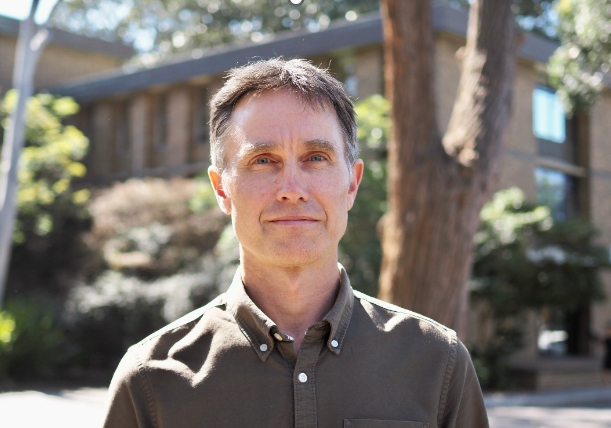

Professor Ben Newell is the Director of the UNSW Institute for Climate Risk and Response, and a professor in the School of Psychology at UNSW Sydney. Ben's role in the institute is to drive an interdisciplinary research agenda, bringing together expertise from behavioural science, climate science, economics and governance to address the risks and opportunities of climate change. Ben attended and presented at the Cop 28 in 2023, and consulted with government on its’ National Health and Climate Strategy. Ben has published multiple articles at the intersection of psychology and climate change with particular focus on understanding of uncertainty and risk.

And finally, Doctor Chloe Watfern is a transdisciplinary researcher, with training in psychology, art and qualitative social science.. social research at the Black Dog Institute. Chloe's current focus is on the intersections between mental health and the natural environment, particularly in the context of climate change. Chloe has presented, published and led creative workshops on this topic for a range of audiences from climate scientists and psychiatrist to young people.

So what an incredible panel we have here this evening, and I'm excited to witness the exchange of ideas from our speakers and hope that this event becomes a stepping stone towards a healthier future for all of us. I'll now hand over to Tegan, who will facilitate the discussion. Thank you Tegan.

Tegan Taylor

So climate change and the health threat it poses should be a nice, easy one for us to wrap up in an hour, I reckon. So let's get into it. Guy, I'd like to start with you, because I think even though Adrian gave us a really good snapshot before, when it comes to the physical health effects of climate that we're already seeing, can you sort of run us through what some of the really big health impacts are?

Guy Marks

Well, I guess, the, the major health impacts of the things that we're seeing from, in change, environmental change that increases the, exposure to hazardous substances, hazardous, infections, such as malaria and dengue and infectious diseases and, and the consequences of this sort of… weather disasters that we're seeing, floods, droughts, and storms and so on, all of which are increasing in the context of climate change and which are causing immediate health effects for the people affected by them. So there's a there's a diverse range of consequences of actual health effects, on climate change. And they have, and they have consequences not only for the people who suffer from those health effects, but, of course, from the health services that have to be mobilised to deal with those health effects. And we've seen some of that in this country.

Tegan Taylor

Right. So the resources that are used as well to….

Guy Marks

….To deal with bushfire people who are exposed to bushfires and bushfire smoke to deal with people who are exposed to flooding and storms and things like that. All of those have consequences for the health system, of course, not to mention the diseases that I was referring to earlier.

Tegan Taylor

Yeah. And then there's the mental health side of things as well. Chloe, can you just sort of paint us a bit of a snapshot there?

Chloe Watfern

Yeah, I mean, it's equally varied as the physical health effects and obviously that linked as well. I guess starting at the kind of, changes, you know, the broader effects of changes to the environment. We have the, you know, direct impacts of disasters on mental health, you know, post-traumatic stress disorder and increased rates of anxiety and depression.

But there's also those chronic changes that happen with, you know, long periods of drought and the effects it may have on livelihoods, and increased, again, presentations across a wide range of mental health problems. And things like, simply a rise in ambient temperatures in a particular climate or environment. as you see those increased temperatures, which unfortunately, we've been seeing the records beaten every year, we also see increased ED presentations for things like suicidality and other common mental health disorders.

So that's kind of the these like really tangible direct correlations between changes to the environment and mental health. But then there's also this, I guess, awareness of climate change and what that does to our psychology, as the future threat. So we're living it now. But it's we know it's going to get worse. we know that there'll be more disasters and we can imagine quite apocalyptic futures, where these health threats are also going to become worse. And so how do we, deal with that psychologically and emotionally. and so there's all these new terms to describe those… that awareness of future threats. And it's, it's still a kind of messy emerging field. But, the kind of most common one that people might be familiar with is climate anxiety. And, I guess one of my positions is that encompasses a lot more than anxiety. And we can feel very mixed emotions about what's happening to the world and the future. So that can be, that can be hope as well as anger as well as dread. So anxiety is part of it. But there's yeah, a mix of these emotional responses.

Tegan Taylor

That's something we're going to dig into in a little bit and we're actually going to ask for your help with that. But before I get to it, Georgia and Ben both been involved in the National Health and Climate Strategy and in the scoping of that, what kind of numbers can we put around the impacts, the health impacts of climate? Georgia?

Georgia Behrens

Yeah, I mean, it's vast. I really when you think about what it is that supports human health everywhere, it's clean air, it's clean water, it's soil that grows healthy food that we're able to eat. It's having a sort of safe and habitable home where you're not going to get everything knocked down by storms and floods and all that kind of stuff.

So, I mean, I think it's probably safe to say that in the years ahead, none of us are going to be untouched from a health perspective by climate change, whether that's mental or physical health impacts. The research out there about how we actually quantify these health impacts in Australia is emerging. It's something where there's, a lot more coming out over the last five, ten years, even in the in the time I've been working on this issue, the research has been burgeoning significantly. But I think that sort of beyond specific numbers, the answer is lots, everywhere, in every way. And, you know, I think that's probably the important message for everyone to take away.

Tegan Taylor

And then if we don't even have a good handle on the numbers at a kind of government and structural policy level, as it sort of sounds, how does the average person make sense of the scale of this threat?

Ben Newell

Right? Yeah. I mean, it's a very, very difficult question to answer. I think we all have a conception of the fact that the climate is changing. People that come to an event like this, are very much engaged in that debate already, are thinking about it in many different ways. We all have a conception of where things are going, and we probably have a conception that that requires us to change our behaviour in particular ways.

What we should be doing to help us either feel better about climate change or to get both our own nation and more internationally going in the right direction for action on climate change, is a multifaceted problem, but I think bringing this awareness and bringing, the discussion and, and the need, you know, the fact that there is now a National Health Climate Strategy that's been put together, that's been, you know, thought about all of the different aspects of of not just the impact of climate on health, but the impact of the health system on the climate is another big topic. I think that that is a step in the right direction to start getting people to think more concretely about what can I do, how can I help?

Tegan Taylor

So, a little bit of participation from you, please. Lovely ones out there. So, in a second, you'll see up on the screen here an invitation. And I might actually get Chloe to talk us through what we're hoping for from you.

Chloe Watfern

So it's. I guess the question asks itself. but, you can interpret it. Really? How you how you will, might want to just respond with a word. You might have a sentence. How does climate change make you feel? In the context of this discussion, you know, feeling is not only like what you're feeling emotionally and physically, but, you know, ‘I might just feel hot’ or actually, ‘right now I feel a bit cold’, but, you know, interpret it as you will and afterwards will also, be in the lobby and happy to talk through thoughts and feelings with you.

Tegan Taylor

So we can already see some questions coming through. the answers, I mean, coming through and I think, there's already repetition there. I feel like a lot of us feel the same way. when I was first sort of encountering this question, it made me reflect for myself and think about what my, answer is. And the word that I come back to is ‘overwhelmed’.

Overwhelmed by the amount of seemingly competing priorities and also a sense of not really having much to sort of, impact on it as an individual, I wonder, I mean, Chloe is something you spend a lot of time thinking about. What's your word?

Chloe Watfern

that word. You know what? I didn't I didn't prepare this one… this answer. There are so many words that I think. I think the overwhelm does put it well, I think motivated as well.

Tegan Taylor

Okay.

Chloe Watfern

Overwhelmed but motivated. And I think that's a challenge because it's such an urgent, problem. And there are so many elements that need to be addressed even within the sphere of health alone.

You can hear from us that there's just these mounting threats and it can be overwhelming, but actually that overwhelm is actually an exciting thing, because it means that there are so many, opportunities for all of us to get on board and do things, and they don't have to be the right things, but they are just something, and this is kind of what I'm learning in terms of climate change and mental health as well, is, we can harness feeling overwhelmed and we can harness feeling anxious or helpless.

And notice… once you start noticing that, then you can start to work out what might I do? slowly. And I still don't always know that I'm doing the right thing, but, at least I feel like I'm working on something that matters,

Tegan Taylor

Yeah. Ben, do you have a word?

Ben Newell

Engaged.

Tegan Taylor

Oh, cool, I love it.

Ben Newell

Yeah, I guess similar to Chloe. It it's a motivating subject for me. It's an engaging subject to me. I mean, the reason I took on the role directing the Institute for Climate Risk in response is because I felt that it was an opportunity to get engaged more broadly with the kinds of people and the kinds of organisations that can affect the change that we need to have, and need to have rapidly. And so I think that that's a way of channelling agency and, and maybe that engagement is partly fuelled by some fear. And I think that's a perfectly useful response to have as well. I do think it's important to, to I mean, I don't go into it in more detail later on, but this notion of, of how does climate make you feel and whether it makes you feel anxious and you know, these different terms.

There's a danger or there's there's a need to distinguish between pathological responses. So and I mean, we're not none of us, mental health clinicians here. And it's important to make that distinction between, you know, I'm not a clinical psychologist.

And in clinical psychology, it's very, distinct and defined usage of terms like anxiety. And I think the debate in academia at the moment is very much as Chloe's saying, there's lots of terms out there ‘eco distress, ‘climate worry’, ‘solastalgia’, lots of different things that are all pointing towards the feelings that people have when it comes time to thinking about climate.

But that doesn't… to link that to a mental health pathology or problem is a complex discussion that needs to be had? because it can I think it can lead to potentially negative outcomes.

Tegan Taylor

Guy, Georgia, your one word answer?

Guy Marks

Look, I am I am very concerned and that's true. but I also, I recognise this problem is a very complex one, and I quite like complexity and I'm challenged by complexity. And so at some levels that that's another part of the way I respond to it. to try as a challenge to, from a scientific and from a public policy perspective, how to solve what is a complex problem.

And I'll just make one other comment about that, that climate change does not exist on its own as and it's not a sole agenda. And, and part of the problem that we often have in public policy is that people focus on an agenda, a single agenda, to the exclusion of all other agendas, and that that isn't what we want to do with the response to climate change.

We have to improve a whole lot of other things in our country and in our world. About equity about health, about equality, a whole lot of things… about justice and human rights. And we need to try and do them all at the same time. Okay? So we need win, win, win win solutions. And that's where the complexity lies.

And so I'm looking to see how we can, how we can solve this problem. And the problem for the climate is it's been excluded from those discussions. So what we need to do is insert it into these bigger discussions about development, sustainable development goals, and other large sort of scale discussions to make sure that there is a voice for that.

Tegan Taylor

I'm curious to hear your one word answer if you've got one ready to go. But I also want to pick up on what guy was saying there about the need to respond to a lot of different challenges at once, which is something that you're doing. Talk us through that process.

Georgia Behrens

I can do 2 in 1. So I would say my word is ‘determined’. I'm very kind of aware of the fact that climate change for myself and for a lot of people in this room can make you feel very overwhelmed, can make you feel very guilty at the way that you are part of the problem, as we all are in many ways very determined to kind of take that guilt and turn that into a sense of responsibility for doing something.

And one of my kind of real role models and mentors in this space is always talked about how when you're working in climate change, whether you need to have an awareness of the fact that you are thinking about things are going to be happening 50 or 100 years in the future, what's actually really important today is what you're going to do when you arrive at your desk at 8:00, 9:00 tomorrow morning and thinking about, okay, look, we've got a lot of competing priorities to juggle.

You're trying to balance out, yet things where there are complex trade-offs, complex, all kinds of different things that you need to be considering weighing up all at once. You need to be doing them fast, and you need to be doing them in a space that is often, emotionally charged and politically conflicted. But if you're going to make any headway in this space, you also need to be able to break that down into, ‘Okay, what am I going to do when I show up at my desk tomorrow morning?’

And that's the only way that any of us are going to make any progress is just kind of being like, ‘All right, I can get through five things in a day’. And these are the five kind of, things that I need to do. And I kind of often go back to that. I know there are any parents in the room, but that song in Frozen where it's like, just do the next right thing.

Tegan Taylor

It’s actually Frozen 2.

Georgia Behrens

Frozen 2? Even better. Yeah. Just kind of thinking about. Okay, well, we're dealing with really long time horizons, massive risk, massive complexity. What's the kind of next best step that I can take with the evidence that I have available and the advice it's available to me, And that's kind of it's yeah….

Tegan Taylor

I feel like there's someone on this panel who's really good at that stuff. I think it's Ben.

How do you how do you help people get their heads around this massive complexity and these competing priorities and knowing where to put your energy.

Ben Newell

Well, can I push back a little bit on the idea that it's massively complex?

Tegan Taylor

Okay.

Ben Newell

I mean, there was a lot of discussion when Covid hit about, maybe our responses to Covid can be mapped on to our rapid responses to climate. And when Covid hit, there was a lot of uncertainty because we didn't know whether we were going to get a vaccine. We didn't know how severe who's going to be, and all of these things.

We didn't know what the solution was or is in climate, we do know what the solution is. We've known it for a very, very long time. We need to cut emissions. I think where the complexity comes in is that I might have that as an overarching piece of knowledge. I know that reducing emissions is what we need to do in order to help.

But there's a myriad different options and actions that I can take in order to do that. And whether the best thing to be doing is, is more recycling. Answer: probably not. Or whether it's to be voting or whether it's to be, finding out more knowledge that I can that I can use, that I can go and have conversations with more people and find out, you know, other sorts of solutions that's complex and bring everyone along that journey in an equitable way. But in some ways, it isn't complex because we know what the know what the solution is.

Tegan Taylor

But at an individual level? Actually, maybe we'll get to that in a moment. because we have had questions coming through from people. If you want to ask a question, you can go to Slido. There's the, activity that Chloe just let us in. But there's also if you want to ask questions, I'll incorporate them in the chat.

But we'll also have some designated time for question and answer at the end. And one of the things that I saw coming through already in the questions that have been given, basically what sort of level is it, the individual responsibility and what level is the putting pressure upwards for collective action? I mean, I started talking about it, and so maybe we should just get into it.

Ben Newell

What I yeah, I mean, I think it's, it's a very prominent issue at the moment in the behavioural science literature and in the debate. So there's been a lot of work, if you think about all of the work on understanding, you know, what changes people's behaviours at an individual level. So, you know, setting something as a default option makes me more likely to choose it. Telling me that, you know, nine out of ten people do this thing, giving me that social norm, maybe that’s the best way to do more.

And there's lots of techniques like that collectively known as nudges. You know, I'm not forcing you to do something, but I'm giving you some evidence that will suggest that this is what I want you to do. There is... yes, those things are useful. And yes, they can they can have some effect, but they're not going to have the big effects that we really need to see.

And that becomes this system level discussion. So how do we influence the systems? How do we influence the policy changes? How do we influence the corporations? And that is a whole… is a bigger, more, more discussion about regulation. So going back to the health strategy, there's now there's lots of stuff in there about what we can do as individuals to reduce the possibility that we have to go to hospital, right?

So reducing the admissions. But there's also lots of advice in there about lots of thinking in there about regulatory frameworks that can change the health system, which in itself has a… we were talking before, 5 to 7% of, you know, Australia's emissions come from the health care sector. That's a lot more than any one individual can be doing.

And so it has to be a combination of this individual and system level. I think where the question for me becomes very interesting is whether: if I'm taking these actions at an individual level, does that give me the sense of efficacy that then pushes me further towards wanting to vote for, wanting to get on board with those more system level changes?

Or am I fine to do everything as normal, not make any personal sacrifices? Because I know that doesn't actually make any difference. But I'll vote for the big policy change. Yeah. which down the track will have an impact on me, especially if one of those policy changes is, you know, there's going to be a frequent flyer tax. If you're going to have a personal carbon budget that you have to adhere to each year or something like that. and that trade-off is psychologically fascinating.

Tegan Taylor

I can see you nodding furiously Georgia. How does that sort of play out in the you're doing policy work?

Georgia Behrens

Yeah, yeah. I mean, it's interesting, isn't it? Because I think, I think what Ben's fundamentally saying is the individual or that kind of structural is a false binary. Right? And probably most people will try and do a little bit of both. And I suppose my advice to anyone who's asking this question about what should I be doing, is just do whatever is available and meaningful to you.

There are going to be some people who don't find it meaningful to reduce their individual carbon footprint or for whatever reason, aren’t available.. that isn't available to them because of the material circumstances of their life. And that's fine. But there are also, I think, going to be people who don't find engaging with policy and big structural questions easy. And if their way of contributing to kind of the shift that we all need to be making is to try and make those individual changes, then that's good and legitimate and maybe a gateway to doing other things at some point as well. So I think it's, it's not either or. Try and do both of you can, but if that's not the one that I was, I was acceptable and legitimate.

I'm someone who kind of probably started off being someone who was looking at how to have a more sustainable diet. And then.. now I do climate change kind of full time for a living. to me, that's really meaningful because I think that, you know, as a government, you can make a massive difference. And you, it's, it's an incredible thing that there's now a team of 15 of us who are sitting there thinking every day, like, how do we make our health system net zero? And as much as possible, eliminate that 5 to 7% of Australia's emissions that are coming from the health system? Or how do we make our health system resilient to all the impacts that are coming for it from climate change already? Like that's a really exciting thing and something that I think is important to say to everyone in this room is, my job and the team that I work in and the strategy that we developed is the direct result of people, including predominantly health professionals, having been talking to the government for a decade, saying, ‘We want this, this is important to us. You should be doing this’. And yeah, it took a decade to get there, but it got there eventually.

And now that's out there and there's stuff happening. So, I think, you know, not to call myself a good news story, but my work and my team is a real good news story and is a real kind of, fable about the fact that if you just kind of.. if you persist in talking to the government about the big important changes that you want to see, change can happen.

Tegan Taylor

I do want to dig into this stuff on the health sector and its contribution to climate. But while we're talking about how there can be like a virtuous cycle, Chloe, the sort of work that you're doing is getting people, amongst other things, is getting people to articulate how they feel and creating something with that, that's, art, and kind of allowing people to name how they're feeling.

What kind of impact does that have on how they feel afterwards and what they maybe do with that?

Chloe Watfern

Yeah. I mean, I think relating to what Georgia said as well, we underestimate the power of conversation and acknowledging how much we care and telling other people about it. So often our work, we use that as a vehicle for conversation, and our team at Black Dog Institute uses that across a range of different experiences. But climate is something that is hard to talk about.

I can't remember who on the panel said it, but it is like it's related to so many abstract things, from the atmosphere to cows fart to solar panels. You know, it's it's really is a and a there's a philosopher who calls it, oh, now I'm forgetting what he calls it. But, you know, it's an indeterminate thing.

But it does make us feel things. And the fact that we care can drive change, at many different levels. And so we use art to have that conversation at the level of just two people in a group or, also helping people to kind of spread their message through… to leaders. So I'm interested in this term ‘craftivism’.

I'm not sure if you've heard about it, but using art for activism and using art for social change, craftivism uses art to, make change in quite a gentle, quiet way like you might. And the Knitting Nanas are a great example if you've heard of them. If you're into climate action, they, they knit and they protest fossil fuels and talk to government, but we use it in kind of other ways to create messages, to share with, with leaders who are making decisions about climate or even just with someone else who might care. And then you have these ripple effects. I mean, Ben might have a different perspective on the kind of psychology of these nudges, and you know, how they work. But I guess I come from a kind of. Yeah, an intuitive, noticing the ripples as they, kind of map out and even in my own life, how having those conversations have shaped me and others around me.

Tegan Taylor

Is it not a bit like climate in itself, where there's small things that we can and should be doing, and there's also really big things that we can and should be doing, and we can have both. Ben?

Ben Newell

Yeah. I mean, I think there's, there's, there's obviously value in different ways of approaching the topic in the conversation with people. I mean, I suppose my, my way of approaching understanding the actions that, that are going to be effective or understanding the way to communicate with people, that it's going to be effective is coming from a much more, experimental side where I, you know, I would I would run an experiment on lots and lots of people rather than having two people talking with each other about the topic.

And then I'd look for the evidence, you know, statistically and see, does that predict a certain patterns of effects? you know, it's not for me to say which one of those is better or what sort of evidence you get from one or the other. But I think it when it again, getting back to the kind of, the, the effect of climate on our mental wellbeing and mental health, I do think it is important to think carefully about the science behind the treatment and the efficacy of the treatment.

Whether this is something which is saying, you know, we're acknowledging that climate makes you feel different, different emotions, that's okay. Are we taking that to another level where we're saying: your feelings, emotional reactions that you're having to climate are having an impairment on your ability to function? And so when it when you get to that sort of pathologising or clinical implications and you're saying, you know, people, people who are being treated for anxiety and depression are being treated for it because they… it's reached the point where it's having an impairment on their functioning.

And I think the debate in the literature about what, reactions to climate, and whether we should consider those things as things that need treatment or can be treated - because it's a very different type of response to if you think about an anxiety response where it is often, an irrational basis for, for it. In the climate there may be a rational reason that we're worrying and we're concerned, and therefore the techniques that might be used to treat a standard kind of anxiety and depression may not be appropriate in this case.

So I think it's very much an area where the science base is emerging. And I think that, you know, the techniques that Chloe and her team are using, to my mind, a different way of thinking about the problem. And it's just important not to conflate the two that that someone that says, ‘I've got climate anxiety’, what that means to them and what that means and implies for the broader conversation about treatment is something which I think really requires careful discussion.

Tegan Taylor

Do you want to add to that, Chloe?

Chloe Watfern

Yeah, no, I'm completely, in agreement that this is not, you know, maybe talking about feelings in response to climate change, it's really important not to pathologise them. And I don't think we need to really reach for diagnoses yet, but we absolutely need to be able to negotiate when people do need clinical support and need to see a trained mental health professional.

And when people want a space to be able to talk about how they feel and share it with others, and that that line is still not clear. But I think that.. I think coming back to like, let's do something. I think we kind of know that talking about like, what we're doing and what kind of a growing community of practice here in Australia and internationally are doing is helping to start to untangle that.

But also, people seem to want to be able to start talking and have permission to talk, and doing that in a non-judgmental, non-clinical setting seems to work. and partly because, I think it's tapping into something deeper that might be wrong about how we understand mental health and what constitutes mental health. And maybe resisting diagnoses in general and understanding that how we feel is linked to these broader systems. And I think that comes back to what you were saying earlier around, is it the individual or is it the system? I think what interests me in this emerging field of kind of climate psychology is its links to traditions of ego psychology and understanding the mind within these broader networks and ecologies. And if we can start to really feel that in ourselves, I think that's part of the cultural changes that are required of us to not feel alone, like I need.. there's something wrong with me as an individual.

I'm worried about climate change. This is a problem that I need to go fix. But no, I'm feeling what's going on in the world. I'm responding. And you know, we know this about a lot of other mental health conditions, not all. And there are very important distinctions to be made between kind of organic and, you know, severe mental health disorders and some of those common mental health problems like depression and anxiety and each of those four within spectrums as well. It's so complicated that I won't go into it. But, how is the way we feel a function of stigma and social structures, patriarchy, colonisation, all those things. So, yeah.

Tegan Taylor

Massive can of worms. Keep your questions coming via Slido – we’re #climate tonight. I do want to come back to this really important intersection between climate and public health and what the… how the public health system is butting up against climate change. Guy, you sort of mentioned a few things in passing at the top of the show, but at the top of the show.. it’s not a radio show tonight. It's just a bunch of friends having a chat. but what are some of the most pressing health concerns with climate related changes that we're seeing here in Australia Guy?

Guy Marks

Can I just say one other thing? Coming back to the last question before we… I will answer that question, but I think it is important that this question of an individual versus collective action is very important, really the main levers and the most important changes, and those are going to come from government and perhaps from large scale private sector players.

They're the ones who are going to make changes, that they can make changes, not only that are effective for climate change, but improve, make sure that we share the burden equitably. and that, beneficial for other sectors. And that requires essentially regulation and, and incentives and all of the levers that exist within government.

But that's not to say that individuals don't have a role as well. And we, of course, live in a democracy and we live in a mixed economy. And so one of the ways in which we demonstrate as individuals that we want this change is to, is to live the change ourselves. And I think that has been an important driver for political change in Australia.

More and more people are not just voting for climate change, but they're living. They're putting rooftop solar on their roofs. They're doing whatever. They're doing all sorts of things that they can do. And that has an impact. And I think also with the, you know, the private sector also is a major contributor, whether they’re manufacturing battery electric cars or internal combustion engine or diesel cars.

You know, they respond to private what consumers are buying and how consumers are behaving. So I don't I think we can think of at a political level, we should think of this as, as both something that has to happen systemically, but also that we as individuals can have a role in, iin many different ways.

Now to turn to your things about health. You know, my, I should really stick to the areas that I know anything much about, which is not all of health. I have to say, as you heard earlier, I'm a respiratory physician and I know a bit about lung disease, and also, I've spent a fair bit of time working on air pollution.

And I just want to talk first of all about, you know, the effects of air pollution and the fact that there are, in responding to climate change, many opportunities to have a double win, actually, to reduce emissions of carbon of carbon into the atmosphere, which reduces global warming, warming, but also to reduce emissions of other toxic substances, particulates and nitrogen dioxide, into the atmosphere, which also has adverse health effects.

And but what we need we need to be deliberate about that. We need to make sure that when we're making these changes, we're making changes that are actually beneficial for carbon emissions and for air pollution and for air quality - actually, not just ambient air quality, not just outdoor air quality. But there are many issues now and much more focus on safe indoor air environments from a whole range of different perspectives.

The perspective of you know, exposure to smoke, exposure to various gases, but also the exposure to infections. This became a big issue during Covid. And, we recognise that respiratory viruses that are an important problem. We need to make sure that our solutions for, reducing carbon emissions into the atmosphere and reducing global warming are also solutions that help to solve these other problems.

One could make, you know, the same argument about other things. Ben raised the issue of, you know, health sector contributions towards, towards emissions. And that is a significant thing. And that’s what’s in your report Georgia, about the fact that the health sector needs to do things that can reduce its emissions, but we need to do so in a way which actually improves health outcomes and not, devalue or, degrades health outcomes for people and that is possible, but we need to be deliberate about it. We need to be thoughtful about it. And that's where some of the complexity rises.

Tegan Taylor

I am keen to talk about solutions. I think broadly, we sort of what has been said before, we already know what the answer is. Given that this topic is focused on health, I'm keen to talk about ways the health sector can be part of this solution. You sort of alluded to that there Guy. Are there some specific examples? Maybe Georgia, can you speak to some specific examples of where this is already happening or where there's some easy wins?

Georgia Behrens

Yeah, definitely. So I mean, this this stuff that you can do within the health sector that will have a significant impact on the emissions that are coming from the health sector. And I can talk about those. And then there are also things that the health sector and health professionals can do around highlighting and promoting the health benefits, as Guy was saying, of these broader kind of changes in our society to reduce emissions.

So, I mean, one really nice case study that was brought to our attention as part of kind of consultation for developing the National Health and Climate Strategy, was this randomized controlled trial that they've done that in Victoria, which is about doing energy efficiency upgrades to low income homes in Victoria. And they basically did some very, pretty simple, pretty cheap energy efficiency upgrades to these houses to basically keep them warmer during winter, cooler during summer - insulation and all that kind of stuff.

And it was about $2,000 in investment. They did a randomised controlled trial, and they were comparing what the health outcomes were from people who had this intervention in their homes and people who hadn't. And they found that the health, kind of healthcare usage of people in the houses that it had, the energy efficiency upgrades, was $800 a year less the people who hadn't had energy efficiency upgrades.

So that meant that kind of these, these installations would pay for themselves within three years, but would last for 20 years at a time. And I think there's a really important role for the health sector in saying, look, there are things that we can do in people's houses that we can do in that built environment, that help to reduce emissions because things are more energy efficient, for example, but also have really significant health and quality of life impact.

So that's one really important thing, I think in terms of what we can do in the health sector, there's a few things. The first is kind of broadly investing in all the kinds of public health things that we would like to see. So you keep people healthy and well and keep them out of hospital. Therefore, not requiring the use of emissions for their treatment and care in hospitals.

But other things that we can do are things like reducing a lot of the practices that do occur in hospital at the moment, that have really not particularly good evidence for having benefit to patients. So over investigation, over diagnosis, over prescription sorts of things that aren't doing patients any good but are having cost to the health care system, both in terms of dollars and in terms of carbon.

That's really important work to be done as part of implementation of our strategy to identify what those are, and what kind of incentives and regulation and everything we can put in place to try and reduce that. And then I think the sort of final thing that you can be doing within the health system is looking at, where are there things where it is really necessary care.

We haven't been able to prevent this from happening. It's not a case of over investigation or over-diagnosis. Someone really needs this treatment. But how can we deliver the care in a way that is as low emissions as possible? So that might be something as simple as having solar panels on the rooftops of the hospitals, so that all the electricity that's going into the treatment of patients is zero emissions.

But it's also stuff like looking at life cycle assessments of various different products to make sure that, you know, if there's medicine A in this medicine B, they do the same thing and one of them is more emissions intensive than the other than we're always giving medicine A, so a whole range of different things, you know, B to do list that our team obviously has, but, important work to be happening.

Tegan Taylor

Guy.

Guy Marks

Yeah. I mean, I agree with all of you just said Georgia. Or perhaps I'll give an example of medicine A versus medicine B, and it's something that's fairly close to me. I think there's probably about 300 people in this room. And I would guess that therefore there are about 30 people in this room who use inhalers for asthma or COPD, about 10%.

And it turns out that many of the inhalers that we're using at the moment are quite… are used as a propellant gas, not as the actual drug that you use, but as the drug that allows the drug as the propellant, that allows the drug to come out of the inhaler, have chemicals that are ozone depleting or, global warming have global warming potential, and it's actually represents quite a significant amount.

It's hard to believe that that little tiny puff that you have is having a significant impact. But it is tending to, and it is possible to produce devices which have much lower, potential, actually. But it's also possible to treat people better for asthma with newer regiments that mean that they need to use less doses of the inhaler.

And so lots of.. there is a win-win potential situation here where we can about improve the life, the quality of life of people with asthma, and we can reduce the, the contribution to global warming of the device, of their treatments. And that requires essentially some development by, the companies. And it requires, again, regulatory decisions.

It's not really a decision that you are in much of a position to take as an individual, or even the doctors are not in much of a position to take. It requires industry and government to work together to produce a better solution. So that's one example of where there is a potential for a change in health… direct potential for the health system to make lower contribution.

Tegan Taylor

I do want to get to your questions and you can continue to submit them at Slido. Our hashtag tonight is climate, and I think I just want to jump straight in with this one which says, and I've lost it now, this one's for you, Ben: ‘Is it best to scare people with the truth or sugarcoat?’

Ben Newell

There's no simple answer to that one. I mean, I, I think… Often people will say, ‘Oh, no, you don't want to overwhelm, you don't want to scare people because it will it will demotivate them. It will lead to this sort of spiralling of disengagement’. A colleague of mine in, UQ came and gave a talk at the, at the institute late last year, and he was very, he was very much of the opinion that he didn't see the evidence on that when it came to the climate debate, and that actually, I think the phrase he used was, you know, striking fear into people's bellies was what we really needed to do to start action and not sugarcoat it. I, I think that, you know, for all the reasons that we started off talking about, yes, we know what the solution is, but that doesn't mean that the future outcomes are not still very uncertain. Lots of different versions and scenarios that we can play out, and I think that it doesn't serve us well to say, you know, ‘Everything's going to be rosy’ or ‘Everything is going to be disastrous’. It's acknowledging, yes, there's uncertainty in the pathways that we're going to say there's vast uncertainties in the projections of the climate models that we have that, you know, and trying to map out that future for us and acknowledging what those uncertainties are and what those unknowns are a part of it.

Now, people are often very uncomfortable with those uncertainties. But I think we need to get to a point where people can have a tolerance of the uncertainty, knowing that there are things that we just we cannot define at this point, but not so completely abandoning the idea that it's all going to be bad or it's all going to be good. But understanding that there are things that we know what to do, we know how to take action, we know what the, what steps are fundamentally important. And that's what we should be focusing on, not the apocalypse.

Guy Marks

In public health, there are three very major examples of where rising anxiety, essentially in people has apparently had a profound impact on behaviour. The first is the Grim Reaper ads around AIDs in the 1980s, which did have a profound impact. The second is about motor vehicle accidents, trauma. It's less clear, but probably did happen. And the third is around tobacco. Those three things, big issues in Australia and in the world in general, and all of them have really featured anxiety inducing, if you like…

Ben Newell

Or negative emotions.

Guy Marks

Negative emotions, yes, in people as a vehicle to get them to engage and perhaps to change behaviour.

Ben Newell

And I think there's it's a it's again a very, active, fertile area of research in kind of climate psychology areas, understanding what those emotional appeals are and whether one way of framing it is better than another. And I think I think the jury's still out, but the comparison with the public health domains is often invoked.

Tegan Taylor

A question from someone asking, ‘In terms of health care, what immediate adjustments need to be made to handle the influx of people needing help?’ Chloe? Sorry, Georgia.

Georgia Behrens

Yeah, it's a really good question. I mean, something that we think about quite a lot is, making sure first and foremost that our primary care providers - so GPS, community health nurses, community mental health practitioners – are supported and resourced to be able to prevent the influx of, kind of, health impacts of climate change as much as possible.

And that kind of takes a few forms. The first is, I suppose, just good old management of chronic conditions and prevention of the onset of chronic condition in the first place, because a massive, kind of, proportion of the burden of disease from climate change is just going to come from the fact that climate change makes people's existing respiratory, cardiovascular, mental health conditions worse because they're too hot or the air’s too polluted or something like that.

So making sure that primary care is well supported, to be able to prevent and effectively manage those kinds of conditions at a baseline is really important. And making sure that, you know, primary care is supported and resource to be able to do that is really important. I think on top of that, there's, I suppose, the more acute end of the spectrum, of thinking about, okay, well, there are going to be in some instances really well, increasingly frequent severe disasters.

So the kind of things that we might picture a little bit more when we think about climate change and the health impacts: bushfires, floods, people clogging up emergency departments, because there's been some kind of acute event. I think there's a lot of work that needs to be done there. There's a lot of work about helping health services to understand, okay, this is what the future scenario is going to look like.

And this is what it's going to mean for you. Not only are you going to have more people arriving at your door, but your power might be out, your basement might be flooded so your IT systems are going to fall down. Your staff might not be able to get to work because they're all going to be blocked off by the same flood that's affecting everyone else. So I think it is as much as anything, an exercise in helping health service providers to understand what the future is going to look like. Accept it's uncertain, but try and put some contingency planning and some capacity building in place to be able to kind of flex with those pretty scary scenarios that are probably going to be landing for them.

So it's, it's, it's prevention as much as you can, but what you can't prevent, being ready to kind of adapt to and flex to, later on.

Tegan Taylor

Yeah. There's a question here from Tanya that I want to put to you guys. ‘How do we need to have equity as part of the consideration when we're discussing a transition to net zero?’

Guy Marks

Yeah. Thank you for that question. I think it's a very important question. It's particularly important question when we think about it in a global context beyond Australia. But there are equity issues even within Australia. And I alluded to that earlier, that if there are changes that need to be made that have economic impacts, we need to make sure that those changes are made in a way that affects people in a fair and equitable way.

But at a global level, you know, we have already so much injustice and inequity, that also needs to be tackled. You know, I'm working at the moment on, on asthma, for example. And, you know, in Australia, very few people died due to asthma, even though it's quite common here. In India, half a million people a year die due to asthma, largely because they don't have access to the effective treatments for asthma.

And many people in Africa also die. Many countries, there are a lot of deaths due to asthma, simply because people don't have access to the treatment. So that actually comes back to the issue I was discussing before. If we're going to change the way in which we create inhalers, we need to make sure that's done in a way which actually increases accessibility and doesn't decrease accessibility to people in the global South. And you know, there are I guess it comes back to what I also said earlier, you know, that we need to solve several problems at once here. We can't just focus on one problem. We need to put make sure that climate action and the things that we need to do to come out, front and centre of the discussions we have about solving all the other problems about, you know, undernutrition - vast amounts of the population in the world and not getting adequate nutrition at the moment for example -how do we solve that in a way which is not adverse for the climate and which is in fact potentially beneficial for the climate? How do we, you know, if you got anybody who's been to New Delhi or Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh city or Bangkok recently, there is almost impenetrable smog. Essentially, it's often called fog.

But it's not fog, it's smog, and how do we battle, you know, to improve air quality at the same time? And in many cases, we will. You know, obviously, much of that is coming from coal burning power stations and from internal combustion engines and if you deal with both of those, you deal with both climate and emissions into the environment.

But.. so there are many win-win situations. But we need to make sure that we're generating those win-win situations. And we're not at least we're not making changes that are increasing inequity and increasing injustice in the world. And in fact, that we're making changes that are improving equity and justice.

Tegan Taylor

Chloe, one for you. Andreas is asking, ‘How do you distinguish the effect of climate change on mental health from other changes that are also happening, like rising inequality and cost of living, that sort of thing?’

Chloe Watfern

That's a great question. And that's a question for an epidemiologist perhaps - not necessarily in my skillset. But I guess we have kind of studies that targeting specific areas, for example, in the disaster literature following an acute stressor. And then we know we can be pretty sure that that's leading to the increase in, you know, rates of whatever is being measured, whether it's anxiety or trauma.

And then we also have, I guess, kind of surveys and other tools that are looking at those specific constructs and then controlling for variables, which, is kind of beyond my skill set, as I said. But do take those things into account. And, you know, you need to interrogate the quality of the methodology and how they're doing that when you're looking at that data. But it is, you know, our mental health is so connected to all these different interconnected systems. So, as we're kind of seeing, you know, not none of those are occurring in isolation and climate change. Then you're there are these there are these loops that are happening as well in terms of how, you know, like the cost of living crisis and, you know, the cost of energy and those things are feeding back from some of the climate related, events and the global context. yeah.

Tegan Taylor

Did you have something?

Ben Newell

Yeah, I think it is an important distinction to make because again, if you think about the way that, anxiety is assessed, usually it's not linked to a specific stressor necessarily. So when people are being diagnosed, again, I'm not a clinician, but when people are being diagnosed for anxiety or depression, the kinds of instruments that that are used, are not asking them to link that to a specific thing like cost of living or whatever.

Whereas these measures that have been developed for like climate anxiety or eco distress, whatever are specifically asking about climate, but, you know, this is a discussion that I think is very, prominent at the moment. And a PhD student of mine who's in the audience, we've been discussing and looking at a lot of these different measures that measure lots of different, different constructs.

And we have a discussion the other day about is it partly, you know, that there were a few measures that came out in the early 2000s and then in the last 2 or 3 years, it's just been this explosion of lots of different measures of various different things of eco distress. And is that because this is an emergent phenomena, or is it just the thing at the moment that people are linking things to?

And you go back a few years ago, these measures of nuclear proliferation anxiety, you know, so it is it just, ‘I'm generally concerned about the world's going down the tubes’, or is it specifically the climate thing? And those are important conceptually really important things to tease apart.

Tegan Taylor

Yeah. We're getting a lot of questions about animal products in our diet and the role of them in both climate change and health. People asking you about veganism or calling for action on reducing meat consumption and, referencing the EAT-Lancet Commission on Food. Georgia, do you want to speak to that?

Georgia Behrens

Yeah. I mean, I think that this is a case where there are some really nice synergies in terms of what we know we need to do to improve health and to reduce emissions. We know that the burden of disease from kind of, diet related issues, which is not just about meat, but has to do with meat and red meat consumption, but also kind of consumption of highly processed foods more generally, which are also emissions intensive - we know that there is a really high burden of diet related disease in Australia and in and worldwide, and that the kind of foods that are responsible for a lot of the burden of diet related disease are also responsible for quite high burden of emissions.

So there are some really great studies showing that basically, first of all, if you just helped more people to eat in compliance with the current Australian Dietary

Guidelines, so more fruit and vegetables, you have lower emissions and a reduced burden of disease. But there's also some really interesting work going on at the moment with, the National Health Medical Research Council. They are doing a review of the Australian Dietary Guidelines. And when they put out to kind of Australian, the Australian public, what's important to you in terms of the update to the Australian Dietary Guidelines? One of the things that came through was sustainability and whether that should be incorporated in some way.

And so that's some really interesting work that's happening at the moment with the NHMRC, on how might this be something that we could consider in a future iteration of the Australian Dietary Guidelines, and what would that look like? Making sure, of course, it's balanced up with all the other things you need to think about in terms of dietary guidelines. But I think there's movement there. And, definitely a lot of opportunities for making people healthier and reducing emissions at the same time.

Tegan Taylor

A question here from someone who, I'm assuming is a student - and I'll let you guys fight over who answers it - this person's asking, what specific contributions can aspiring public or global health practitioners, health managers, etc. make towards addressing the intersection of health and climate change? Don’t all mob me at once.

Guy Marks

Well, I mean, I, I think, you know, the sorts of things you've been hearing about… The answer to that really is the sorts of things you've been hearing about today. We need to find solutions. And some of that involves research where we don't have the solutions. And many of us here are involved in the research enterprise.

And that is really about asking questions and answering them, and hopefully asking questions that are relevant to this problem. And so I think, as you know, as a researcher, I think that there is a role for public health and global health people to find knowledge and to contribute new knowledge. But having… but there is already a lot of knowledge.

And the next is how do you translate that knowledge into policy and into practice? And as a public health or a global health practitioner, you have a role for both designing policy, creating policy and also in seeing that policy implemented, in various different settings. So there's a whole cascade of things: there’s generation of knowledge, there’s translation into policy. And then implementation into practice and public health, health people in general can play a role at all stages in that, in that process and hopefully will. So I encourage you to do so.

Tegan Taylor

So maybe just to close, I'd love to get from you, for people who have sort of listening to this, I'd be curious to know, maybe just think about it in your own head, whether your word might have changed? Whether you're feeling more depressed or more empowered. I haven't quite made up my own mind yet, but if there's sort of one small or one big, or both, action or idea that you hope people take away from these, what would it be? Georgia?

Georgia Behrens

Mine is always when people ask me this, ‘Start where you, do what you can’. I think as a medical student, I started med school. I was really interested in climate stuff and kind of thought, oh, gosh, do I need to quit medicine in order to do stuff on climate? And fortunately, the answer was absolutely not by studying where I was, which is in the kind of health care world, and connecting with other people in the health care world who are interested in climate change, I found a niche, I found cool, other things to do, and now here we are.

And I think there's a real lesson in that for everyone, which is like, you don't have to necessarily change everything you're doing and cast it all aside. Just stop where you are, find something you can do there, connect with other people and your momentum will build from there.

Tegan Taylor

Guy?

Guy Marks

I don’t think there’s much I can add to that. Actually Georgia, I think what you said is excellent. I feel a bit more optimistic after this discussion, actually, with my colleague, with the colleagues here on the panel. And I think particularly I feel, sort of, that we're in good hands with these colleagues. But, you know… I think what Georgia... She speaks for me too. That's what I feel. I feel I'm in a place and have been in a place, and I have some skills, some.. occasionally people listen to me. I don't know why, but, so I'm in a place where I can take some action, and I try and do what I can in that place.

Tegan Taylor

Ben?

Ben Newell

Yeah, I'm going to be boring and say similar things/

Tegan Taylor

Oh, come on!

Ben Newell

Well, I think stay Informed is another one. Another simple thing that you can do. understand the importance of evidence in deciding what it is that you want to do. So try and get the best evidential foundation for any actions that you do want to take or in evaluating, you know, the fundamental science or the fundamental policy effectiveness or whatever it is that you're that you're assessing.

And, and yeah, be engaged to use whatever platform you have to do whatever you can to engage other people. I mean, I think that that, that gives me optimism about this, about this issue and this question is the number of times people keep asking me that question - because that suggests that a lot of people want to be informed, want to be doing more about it, as more and more of these kinds of events, you know, the government is doing lots of things, pushing in lots of different areas towards this general direction. And that, I think, is something which we should all feel empowered by.

Tegan Taylor

Chloe?

Chloe Watfern

I'm going to try and say something slightly different, but it's not hugely different. I just was reflecting on the importance of self-care. And thinking about self-care broadly. You know, when our self is, when our selves are so connected to all these other people and places, but, to sustain the work that we all need to do, it is very important to be mindful of burnout, because I just suddenly started feeling a bit tired - like it's not that late, but actually I'm feeling a bit tired from a long day of work.=

And what might I go away and do just to look after myself a bit? Because working on climate in whatever field it is, but the health impacts of climate, it has a mental toll. It might not be a clinical mental toll, but it can drain. It's super motivating. But it's also you're confronting quite alarming facts and figures on a daily basis.

And so often in our workshops, or any kind of programs that you want, at Black Dog Institute will have a kind of a check out, like what will I do to take care of myself after this moment, where I have been dealing with something that is emotionally loaded or kind of thorny terrain. And so, I think I'll go home and read my book.

I'm reading Overstory, a wonderful, book about trees and feeling and, you know, just think about how much I love trees. And that's kind of what keeps me going while I'm doing this work is, the love I have for really special places. And the people that I share this work with who happen to be here today. So, yeah, I think we can be selfless and heroic or, you know, hopelessly heroic in the climate world and we need to remember that it's not on one person. And you can take a break.

Tegan Taylor

So go home, read a book about trees, and at 8 or 9am, tomorrow morning, when you get to your desk, take an action. Thank you so much to our incredible panel.

UNSW Centre for Ideas

Thanks for listening. For more information, visit unswcentreforideas.com. And don't forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Dr Georgia Behrens MD MScPH

Assistant Director - National Health, Sustainability and Climate UnitGeorgia is Assistant Director in the Australian Government’s National Health, Sustainability and Climate Unit. She has worked in climate change and health in a wide variety of advocacy, research, and policy roles. She trained and worked in clinical medicine, before completing an MSc Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine as a General Sir John Monash Scholar.

Scientia Professor Guy Marks AO

Physician and epidemiologist, Woolcock and UNSW Medicine & HealthGuy Marks AO FAHMS is Scientia Professor at UNSW Sydney and an NHMRC Investigator Fellow. He is a respiratory physician (pulmonologist), public health physician and epidemiologist. Since 2019, he has been President of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. His clinical practice at Liverpool Hospital includes clinical and public health management of people with TB. His research, both in Australia and in Vietnam, focuses on public health approaches to ending tuberculosis as well as the health effects of air pollution, safe air, and chronic respiratory disease.

Professor Ben Newell

Director, Institute for Climate Risk and Response, UNSW SydneyBen Newell is Director of the UNSW Institute for Climate Risk & Response and a Professor in the School of Psychology at UNSW Sydney. His research focuses on the cognitive processes underlying judgment, choice and decision-making. His role in the Institute is to drive an interdisciplinary research agenda bringing together expertise from behavioural science, climate science, economics and governance to address the risks and opportunities of climate change. He has published multiple articles at the intersection of psychology and climate change, with particular focus on the understanding of uncertainty and risk. Ben is lead author of the books Straight Choices: The Psychology of Decision Making, and Open Minded. Ben is a member of the Academic Advisory Panel of the Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government (BETA), and was part of the Chief Medical Officer’s advisory group for the National Health and Climate Strategy.

Dr Chloe Watfern

Research Fellow, Black Dog InstituteDr Chloe Watfern is a transdisciplinary researcher with training in psychology, art, and qualitative social research. Her current focus is on the intersections between mental health and the natural environment, particularly in the context of climate change. She has presented, published, and led creative workshops on this topic for a range of audiences, from climate scientists and psychiatrists to young people. She is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Black Dog Institute and a Research Associate of the Knowledge Translation Strategic Platform of the Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise (SPHERE).

Tegan Taylor

Tegan Taylor is a multi-award-winning broadcaster for the ABC with a strong interest in health and science. She hosts Life Matters on Radio National as well as the cheeky health podcast What’s That Rash? Previously, she’s hosted Radio National’s Health Report, Quick Smart, Ockham’s Razor and Coronacast. She’s received a Walkley Award, the Eureka Prize for Science Journalism and her work has appeared in the annual Best of Australian Science Writing anthology, of which she is co-editor in 2025.