The Case for a Republic

I think that Australia has always overestimated the practical value of a connection to the British, and the British Empire and British identity.

After the coronation of King Charles III, many Australians reflected on their relationship with the Crown and what it means for our country's future. Australia is a very different country now than it was 100 years ago, and the idea of a monarchy resonates differently today for our vast multicultural population.

A hushed conversation has been stirring for some decades now, but since the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, it’s reached a fever pitch – orbiting the central question: what is Australia’s national identity? As our government strives to be more progressive, how can we reconcile the complex relationship between the Crown and Indigenous Australians, and the impact of colonisation on the ongoing struggle for recognition and reconciliation.

Hear from Craig Foster, former Socceroo and Chair of the Australian Republic Movement, Megan Davis, Cobble Cobble woman and Pro Vice-Chancellor Society at UNSW Sydney, and Nyadol Nyuon, Director of the Sir Zelman Cowan Centre at Victoria University, in a panel discussion hosted by constitutional expert and UNSW's Deputy Vice-Chancellor, George Williams. Together, they explored the benefits and challenges of severing ties with the Crown, the role of the Commonwealth in Australia's future, and what steps we can take to make this a reality.

Presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and supported by the Australian Human Rights Institute.

Transcript

UNSW Centre for Ideas: Welcome to the UNSW Centre for Ideas podcast – a place to hear ideas from the world’s leading thinkers and UNSW Sydney’s brightest minds. The talk you are about to hear, The Case for a Republic features former Socceroo and co-chair of the Australian Republic Movement Craig Foster, Cobble Cobble woman and Pro Vice-Chancellor Society at UNSW Sydney, Megan Davis, Director of the Sir Zelman Cowan Centre at Victoria University, Nyadol Nyuon and UNSW’s Deputy Vice Chancellor, George Williams and was recorded live. We hope you enjoy the conversation.

George Williams: Welcome. It’s so wonderful to see such a big crowd here tonight for the The Case for an Australian Republic – we can’t quite offer you the pomp of The Case for the Monarchy that you had on Saturday night, but the Roundhouse is about as good as you’ll get, I think. So, it’s great to have you here.

My name is George Williams, I’m delighted to be hosting this event tonight which is presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and the Australian Human Rights Institute, and I’d also like to begin by acknowledging the Bidjigal people who are the traditional custodians of this land and to pay my respects to elders’ past and present. I'd also like to say in that acknowledgement – how proud I am of the University of New South Wales that we're right behind the Voice, our own Megan Davis who we will hear from soon. She has been one of our main advocates nationally for the Voice and this university believes in Indigenous empowerment and in supporting a yes case at the referendum, while recognising of course, that our community is free to express whatever view they wish. Now, tonight’s event is The Case for a Republic and of course, it could not be better timed.

Today is the day to talk about these issues. Today is the day perhaps to come to terms with how we might have been feeling on Saturday night, as I'm sure all of you bowed down and paid homage to King Charles III. I tried to get my kids to do that, I must admit on Saturday night and had no success whatsoever, which gave me some hope for the Republican cause in the younger generation. We've got a really great panel tonight who are going to explore issues about what sort of society and country we aspire to be. How well does our monarchy fit with our sense of who we are and who we aspire to be? And if we do want change, how do we get there? We have had a referendum on this once before, how can we make sure that it's different the second time around?

We're going to have a conversation with the panel, but there's also a chance for you to ask questions, and I'd love to hear your questions from all sorts of perspectives. We’ve got Slido, an online way of asking questions and you can type in sli.do/unsw and put your question there. It’ll come through to me and I’ll ask the question towards the end and subject to how many we get but we’ve also got mics as well. We know some people just love to ask their question hopefully, not at great length, I would say. So, we can get lots of people talking and we’ll have them down in the aisles for later in the session.

But I’d like now to introduce our panelists before going on to a conversation and then going on to your questions, now we’ve got virtually, and this really is Megan. It’s not ChatGPT or anything like that, appearing on the screen. I assure you; this really is Megan Davis and Megan, I think it’s fair to say is one of the busiest people in Australia today and Megan is fighting the good fight for the Voice. She’s a Professor of Law here at the University of New South Wales, she is a globally recognised expert on Indigenous peoples’ rights. She served on the referendum working group which has led to the proposal being put to the people and she’s someone who’s worked extensively with the United Nations. And of course, she was one of the leaders that lead to the Uluru Statement from the Heart and read out the Uluru Statement for the Heart – that invitation, a gracious invitation to the people for the first time and it would be remiss of me not to mention that Megan has a book that will be coming out shortly, published by the UNSW Press called Everything you want to know about the Voice to Parliament, should you wish to know more about that, I hear it’s an excellent work.

Next, I’d like to introduce Craig Foster. Craig, of course, is a decorated football player having had a remarkable career including as captain of the team. He is one of Australia’s most respected sports people as a broadcaster, social justice advocate and human rights campaigner and as someone who has fought for bills of rights and change for many years. I must admit I’ve been inspired over a long time by the work that Craig has done fighting for refugees and now, fighting for the republic – fighting for our identity and our sense of who we can be as a nation. And, he’s also, and you’d have to say most distinguished as a committee member of the Australian Human Rights Institute’s Advisory Committee. He doesn’t get higher than that at the University of New South Wales.

We’ve also got Nyadol Nyuon, who’s also joined us tonight. She recently became the Director of Victoria University’s Sir Zelman Cowan Centre and has spent a decade as a lawyer and also as a community advocate – someone who I’m also delighted to be on the panel with because she also has inspired me in thinking about the possibilities of this country as someone who has been a refugee and has achieved such heights in Australia as an advocate, as a communicator, and also as someone who’s won many prestigious awards including the Victorian Premier’s Award for Community Harmony. She was one of the 100 Women of Influence and also, has a Medal of the Order of Australia. So, we’re very lucky and it’s a very distinguished panel we have tonight to talk about these issues.

So what I’m going to do, I’m going to ask them a question. We’re going to run though the panel. We’ll have a discussion, and then come back to you and my first question is going to be to you tonight – Craig, I’m sure you were glued to your screen on Saturday night, watching the coronation of King Charles III may be hoping for a slip, may be hoping for more, but why do you think that now is the time that we reinvigorate this debate? The coronation is an obvious point but unless there’s more, it could so easily be peter out. So why do you think now is the time for you in the Republican movement as one of its’ co-chairs to take this debate forward?

Craig Foster: Great, thank you very much. I’m delighted to be here with incredibly eminent panel, Megan and Nyadol – two extraordinary Australian women and also, I know you’ve made a large contribution including in this area, George. So, thank you to all and I acknowledge the traditional owners as well.

So, you said before that I fought many causes and for refugees and human rights and that’s very true but you also said that I’m fighting for the republic – actually, that’s not true because, the republic is not a fight. It’s not a fight between Australians and it’s not a fight between Australia and the UK, and it’s not a fight between Australians and even the Crown. It's about all of us coming together and an acceptance of our history and its fullness and in its truth and committing to each other. And why is now the necessary time for a vast number of reasons but I would say, simply this, that it’s time for us to inherit our own country and this week when we saw, you know, a foreign king purport to represent us in 2023 and the values that we have that are so antithetical to what we saw – it was a moment of great contradictions and I think cognitive dissonance for the majority of Australia.

Many Australians have great affection for the royal family and the monarchy including my own mother who loved Queen Elizabeth. Absolutely. She’s not so keen on Charles, I have to tell you. First, she certainly has great affection for Queen Elizabeth, so I very much recognise that there’s many Australians who have great affection for this institution, but we don’t have to be among them. There are a wide variety of views as to their contribution, the British institutions, you know, that we are rightly proud of but also, there is a side of history that has not been told and that has been denied to Australians in many ways, because culturally, we've been in a position where those who wanted to question the other side of the Crown and the monarchy, and their contribution to Australia have been shouted down.

And culturally, it's been seen as something that couldn't be done and they were very much immune really, to accountability not to criticism, not to attack some of this is about, but accountability, which is a key element, or should be of not only us facing our history, but of walking forward in truth and justice into a future where we're all together. We have over 300, extraordinary, beautiful cultural backgrounds in this country and none of them have the opportunity to stand in front of all of us and say, I belong here, and I'm so valued, that Australia has chosen me to represent them. We saw this week – a call from Australia's King for us all – metaphorically, or literally, doesn't matter to take a knee and to pledge subservience. That's what allegiance and loyalty is. It's not a benign pledge. It's not just a group of words that have no meaning. It has great meaning. It says to Australians that you still are subjects.

I am. You are, and so to, are all of you. And I happen to think that we're not, I don't think Australians should take a pledge any longer. I hope that our Prime Minister in the future doesn’t have to suffer the indignity of having to do so or feeling obliged to do so. They can have their own personal views. And again, they might have, you know, personal reasons why they think that thats appropriate, but they represent us. And more particularly, our Prime Minister represents our commitment to democracy and at the moment, that commitment is not full. Their loyalty – his or her loyalty should be only to you and to me, to Australians, and to the concept of Australia, into this land only. I hope that in future that's the only pledge that any Australian where the First Nations, or any of our beautiful cultural backgrounds are ever asked to make again. We are finally, as I want to hear from these incredible people, finally, we are also stepping a path of truth about our history, and I would say that the truth is setting us free because we can have conversations that we were always denied. But true freedom is self-governance and constitutional independence, and Australia owned by Australians and governed by us. Thank you.

George Williams: So I might come to you Nyadol, if that’s okay and Craig’s already adverted to issues of identity and expressing who we are and one thing that you have fought for in particular, is communities. The concept of multiculturalism, inclusion – I’m just wondering how you see the republic and the idea of the republic fitting in with what you fought for? And how do you see this relating to the sort of society you would like Australia to become?

Nyadol Nyuon: So, I think Craig mentioned the concept of constitutional and political independence. I think it’s also a question of an independent cultural identity, one that is crafted by Australians themselves. So, I look at the question of the Republic really, as a question of who we are, the people. And I think historically, and probably today, and if you see where the biggest resistance towards the Republic future comes from, I think it comes from those Australians who see the monarchy as a continuation of their own identity. It provides them a source of symbolic value but also a cultural value, and whenever we have a debate – a lot of questions and the framing about the Republic often come from that very forced narrow perspective and if I am to be bold, say it comes from the perspective of seeing Australia from a very Anglo-Saxon perspective. And so to me, I think there lies both the opportunity but the greatest challenge for a republic’s future because automatically, if you want to become a republic, it challenged those traditional perspectives and the value that people have placed on the British monarchy as it relates to the relationship with Australia.

Now, I think to some degree, Australia – when I say Australia, I mean Australia is crafted through the Anglo-Saxon perspective. I think that Australia has always overestimated the practical value of a connection to the British and the British Empire and British identity.

And as I was preparing for this event, I read a book by two Australian historians called, After the Empire and it notes a point, I think it’s quite useful to read out to some extent because I think it’ll elaborate on some of the challenges that we face especially those of us in support of the Republican movement. But they say, for example, the expectations that British interest will always coincide happily with a community of a race or culture frequently felt out of reality and they point out three examples of how, even as earlier on, you know British interests never necessarily aligned with Australian interests you know.1991 and in 1961, actually, I think this is quite funny, the Secretary I think it’s the Secretary for Commonwealth Relations writes out the Australia and UK colonies, there’s actually Australia, New Zealand, Canada and tell them that they will now intend to limit the word, ‘British’ to only people in the UK and of course, Australia and those countries nicely conceded.

But then there are serious points that they point out for example, the fall of Singapore in 1942 where British commitment to Europe meant that Australia was left undefended and then of course, there was British joining the ECC which directly conflicted with Australia’s economic interest. But despite all those things, there’s always a return I think, in some quarters of Australia back to the motherland or the homeland and that’s why I – I say that, as much as people want to argue about the symbolic importance of it practically it’s never been useful but I think it’s also meant that it has tied us down as a country to defining who we are from a very narrow perspective. It has stopped us not only from engaging seriously with our Indigenous history but it also means that we are unable to explore what it is to be a multicultural society. How does those multicultural differences influence if they should? I don’t argue that they always should. If they should, the institutions that represent us as a country and whether in the 21st century, or is it still the 21st century? Whether in the 21st century, we are served any longer by the need to tie to a colonial empire that is in itself, struggling? I think that the challenges for Australia as a country today are made better by redefining the concept of who we are as a people in a way that truly embraces our multiculturalism. And I think to continue to rely on the idea of driving our sense of self-instability from Britain betrays a lack of self-confidence that we are capable of self-definition. That’s not always going to be an easy task.

It is going to be complex. It's going to be hard. It's going to be challenging. Which values do we uphold? Which don’t? But that’s a struggle that I think the time has come for us to be confident enough to think that we can do it because whether it is intending or being afraid to cut the umbilical cord from the preteen, whether it is us, you know refusing to do that or whether it is the fear that we cut those ties, the mother will slap us down. What that suggests to me is not a relationship of equals, it’s an unhealthy form of co-dependence and I think the time for us has come to do differently.

George Williams: And you do talk about, ‘we the people,’ which of course, the famous opening words to the United States Constitution which, a declaration of confidence as much of independence. If you compare the Australian constitution – if you open it up, you’d actually realise that our Constitution begins that with that immortal word, whereas, not quite as exciting but, whereas the people of the colonies, Western Australia gets left out so it’s not quite the same confidence start that we’re talking about. So, Megan, can you hear us there okay?

Megan Davis: Yeah, George.

George Williams: As we know, this year, there's only one game in town when it comes to a referendum. The Government has committed that there will be a referendum on the Voice, and we can expect that that will happen in the second half of the year. Megan, I'm just wondering if you can reflect a bit on how you see the Voice debate fitting with the republic. And in particular, if we achieved a Voice and a republic, how do you see those two things as working together?

Megan Davis: Yeah, so George, we’ve always felt in particular, you would know from the 1999 republic referendum that not a large number of First Nations people supported it. And it was partly because people felt that we didn’t need a significant shift in sovereignty if we haven’t actually contemplated or grappled with the original agreements that is to say, the position and the role of Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander people in the Australian state.

I remember being a young law graduate, George, working for the UN in Geneva and kind of being really shocked – I mean, I’ve always been a republican – but being shocked when it lost, and then a lot of leaders coming across the work that I did in Geneva. Aboriginal leaders just saying, “no, we don’t support it for a number of reasons”, the PM [Prime Minister] was one but also the fact that the relationship between First Nations people and the Crown is something that mob at that time wanted dealt with before we move into a new phase and the Australian Republic Movement was consistently saying that we’ll deal with black issues after the referendum.

But there was no Aboriginal constituency that felt comfortable with that. That actually, if he just kicked the can down the road that somehow the minimalist kind of republican changes that we were contemplating in 1999 was going to lead to any significant change in the way that First Nations people were heard on this issue of the republic and I mean, I have to say in relation to the IRM [Independent Review Mechanism] – not everyone’s enamoured with what looks like 1999 all over again and when we talk about what significant role constituencies play in the republic, particularly Aboriginal people.

All we hear is that the Aboriginal president will be Aboriginal, which is so super tokenistic. So, for us the Voice has to come first, and I’ve yarn to a lot of republicans about the fact that this referendum has to come before the republic referendum and of course, George, we’re really confident that we’ll win. We will win this referendum this year but it’s important that sequencing because you can’t just kick the can down the road in relation to the relationship of First Nations peoples with the rest of the nation and that involves grappling with what the meaning of the constitutional system now and what that means in the future when we do become a republic. But I have to say, you know, I’m hypercritical of the fact that I think we need to go out to Australians, George, and have that conversation about the republic now because Australia today is not Australia in 1999 and there’s a lot of our multicultural brothers and sisters who come in from all different faiths and all different cultures. They need to say what that model looks like. I don’t think we should be using a copy and pasting model from the past. I think we need to talk to the Australians of today but having said that, I do have to say that I found the weekend just extraordinary, just absolutely extraordinary. You know, a lot of blackfellas – my father, my grandmother – like lots of mobs say that they love the Queen.

George Williams: I think you’re talking about ‘Magic Round’ for a moment, Megan.

Megan Davis: [Laughs] I was not watching ‘Magic Round’ but a lot of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander votes loved the Queen that for all sorts of reasons, not the least that Aboriginal people to have great regard for ritual and tradition and so, we like watching those ceremonies. And people feel very strongly about the Queen, but I must admit, I just felt nothing. I didn’t watch it. I watched it after I got back from ‘Magic Round’, George. And just feel, you know, in a society like ours, in a democratic society like ours, it’s extraordinary. The obsequiousness towards people in who in my view, have never had held a proper day job in their lives. And so, with the Voice referendum coming up, I think the conversation next about the republic is really exciting. It’s really exciting for the nation and it’s really exciting in the same way that the Voice is optimistic. A positive picture of who the nation is and can be in the future. That we can go into the next phase for the next republic or next referendum I should say, feeling the same way, you know, how do we make social change? How do we, as a nation build? And the republic is the start of that conversation once the Voice is settled.

George Williams: Thank you, Megan.

Megan Davis: But you know, I can go on. I can keep going.

George Williams: And I can't wait. I'll come back to you in a second. I'll come back to you. And I'm glad you got your priorities right – sport, then coronation, ‘Magic Round’, then the coronation. I think you've got that right. Craig, we've heard a bit about bit from Megan. And one of the really striking things is how much First Nations have changed their perspectives to and the Voice. First, rightly as Megan has said and that promises quite a different debate next time around on the Republic. But my question is, you’ve laid out I think the case for why you think we should change but how do you think you’re going to get us there? I mean you’re the co-chair with Nova Peris of the ARM [Australian Republic Movement]. How do you think you’re going to get from A to B, and actually get a referendum on this topic?

Craig Foster: Yeah. Great. I enjoyed the perspectives of both Nyadol and Megan and I couldn't agree with Megan more. I think the sequencing is right as we've been at pains to say and that we have to go back in history and heal the wounds before we can carry forward or move forward together. And so, you know, Republicans would look back with regret at ‘99. But, you know, there's a very strong argument that Australia actually is ready now, and in many ways perhaps wasn't then, our conversations about our history and about First Nations and with First Nations have evolved incredibly in the last 25 years. And that’s critically important. So, you know, we’re completely aligned there. And to answer your question also goes to Megan’s point, and that is a conversation for Australia.

So, what we’ve been saying this week is that two things. Firstly, that we’re incredibly sensitive, deeply respectful of First Nations and the need for all Australians to be talking about the Voice this year and therefore, the fact that the coronation occurred, was on one hand, timely, because it’s in the same year and it allows us to see the contradictions between the two. But at the same time, we’ve been very careful, for example, you didn’t see us protesting or you didn’t see us have a huge campaign. You know, we were just talking in media. Various media who are interested in so and so, we didn’t want to invest too much prominence in this moment, in what is an incredibly transformative year for Australia, and moving forward then and looking to next year and beyond. This is something that Australian needs to own.

And that I think is the lesson from ‘99 is that Australians for whatever reason felt that it wasn’t their evolution. It wasn’t the step that they had developed and in the end, didn’t support it. That’s critically important because the republic is about democracy. Republic is about the people and the conversation we need to have next year is exactly what Nyadol said, how does every Australian feel today? Who are we? And how much belonging do people feel that they have an ownership of the country because in order to take that step of final independence and ownership, we need to it on a just basis. We need to it on a truthful basis.

We’re walking that journey now, but we also need to know how all of our communities feel. That's the conversation I'm so excited to have. So, for example, we've been thinking about the participatory democracy and involvement of citizens right across the country. What does that look like from next year on? I've been contemplating going abroad, for example, perhaps even to Ireland to see how their referenda and citizen assemblies work, and trying to get a picture as what is the process through which we can actually have this conversation. So this republic is not about going from 2023, into Constitutional independence. It’s about a journey for all Australians to come to the table and say, “this is what I want. This is how I feel. This is what I think we stand for. This is what are, these are my concerns, this is what I would like to see going forward”. And then, we can extrapolate all of those views of the country, which we haven't done for so long and then we can start to develop what you would call a model as a Constitutional Professor that suits every single one of us. It's that journey I'm most excited about.

But that conversation is critically important and we want to make sure certainly, I want to make sure that Australians from every one of our different communities are heard and have a say, not the usual voices. And that includes me. You know, not those a prominence, not those with platforms. But all of you. And people all around this country, can get into rooms, and can be assisted and guided through the process of having difficult, discomforting challenging conversations about who Australia is now and who it is that we want to be. And when we make that commitment to each other, and we understand all of our perspectives of all of our more than 300 different cultural backgrounds. The next step is an inevitability.

George Williams: Thank you. And I must admit, the idea of the discomfort in conversations reminds me the last time I talked to my teenage son, we won't go there. I mean, Nyadol, Craig has talked about the conversations we will undoubtedly have on this topic over the next few years and I'm just wondering about how you think we can structure those conversations. How can we do those in a way that you think are inclusive? That it’s not just the familiar people talking that we’re talking to new Australians, diverse Australians, the full community. Do you have any thoughts on how we can structure or do this in a way that actually leads to the moment that Craig is hoping to achieve?

Nyadol Nyuon: I don’t know. I think that my honest answer is… I don’t know. But I think that those conversations to some degree are happening. I'm actually trying to find a way of saying this nicely, or not too boldly. One of the conversations I've had with a friend is, what is the role of multicultural communities in the republican debate, right? Because I know for a fact that even take out the context of the republican debate. I don't get seen as Australian by certain sectors of Australian society. And so, whenever I, I go on The Drum or the ABC, I would get often trolls and attacks and abuse, some of it is directly racist. But a lot of it are at the core, the idea that I cannot criticise Australia – that my citizenship is conditional. And it's conditional on just being able to praise and be grateful for Australia, so very condensed sense of citizenship. And I think the same debate is happening. I have seen some comments, especially that it is inappropriate for people like me to comment on the relationship between the monarchy in Australia, because it's not my cultural heritage, why would I understand its significance and its symbolism? And I think that goes to the point that I was trying to make that the question of the republic, in my view is a question of redefining who the people because for long, who the people in Australia, as being predominantly seen from the perspective of one, white Anglo Saxons.

The republican debate allow us to ask ourselves the question, at least, can that be broaden? And I think it needs to be broadened. We can leave aside the multicultural community for a minute but it must be broadened because of First Nations people [being] 60,000 years present in this country. So, we have to redefine who the people are, and maybe after we settled that we can consider whether or not it is broadened for people of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds, as long as they call Australia home and they pledge their loyalty to Australia.

And I think the deeper issue for me is that there is a serious suspicion of people who don't look white in this country, and there is a suspicion that we cannot possibly love this country. That given the opportunity, we'll find ways of betraying them because we do not have cultural roots or cultural heritage that are embedded in the idea that is most readily accepted as Australian. And I really doubt that. I doubt it seriously because I live in those communities, you know, my children's first language – thankfully, my mother is not here – is English. You know, we don't live in enclaves. We speak English, I read my daughter's books predominantly in English. There's a sense of who I am, as a person who can only exist in this country, and so this idea of doubting – our potential loyal to your commitment to this country, is all based on how we look outside. But if you meet a lot of people in this country who might not look like a typical Australian, and I always say about my younger siblings, you know, they are Australians who don't know they're black, you know, and it's because of the way they relate to country, this country in the way they think of who they are. They're not Sudanese, you know, they are very different from the average 12, 13-year-old Sudanese you'll meet in South Sudan. And so, I think on the one hand, yes, opening up these debates, and having them in the right way is optimistic. But I don't think that it should be necessary. I think that part of the process is that it will be messy.

Moral questions – questions about values are inherently difficult and messy, and I don't think we can ever get to a place where there would be a good way of debating that part of maturing as people. I think it's going through that and figuring out how we turn up on the other side. And sometimes we fail, and we have, and sometimes we succeed as we might with the Voice but we must still engage in those conversations no matter how difficult, no matter how messy they are. We can't wait for a time where it is sanitised enough and good enough for us to be able to do it because the time will not arrive.

George Williams: And Megan, I'll direct one more question to you and then, we're going to open it up to the audience after that. So you’ve got Slido on the screen, if you’d like to put a question there or we will have some mics down the aisles as well. Megan, I wanted to turn to a question about political context, which is very front of mind for you at the moment. We've never had a referendum succeed in Australia without bipartisanship and that's something that of course, we've struggled with on the Voice and we may well struggle with on the Republic as well, and we of course, had the ‘99 referendum where we had the Prime Minister of the day campaigning against. Megan, what's your advice or thoughts about the prospects in Australia today of not just the Voice but the republic and being able to achieve success in a referendum when our major political parties don't agree?

Megan Davis: Yeah, it's a good question, George. I mean, my concern about the continual recitation of bipartisanship is a problem, which nobody really knows until it's pointed out to them. Is it just a recipe for shrinking ourselves as a nation, in terms of change? And if we were just all going to operate for all time on the basis of this idea that bipartisanship is the only recipe for changing this nation, then, you know nine times out of 10, we won't do anything. And George, since I joined Gillard’s expert panel in 2010, this was the thing we had to grapple with in Canberra because you know, even though Tom Calma used to say to us all, “leaders are readers, you can’t be a leader without reading”.

For the past 12 years, when you go to Canberra, it’s really clear that most of the politicians haven't read any of the information. So, every time we go to Canberra, you’ve got to start from scratch and brace them on everything and the only thing that they know, and they act like experts on is, bipartisanship. And that's just a race to the bottom. So rather than thinking about what is best for this nation? What is best for the nation in terms of First Nations people? What is best for the nation in terms of the Australian people? What's the best model in terms of the republic, you know? What is the model we should pursue? And then this kind of obsession with bipartisanship, which is, you know, something that comes from an era in which there was no social media, in which Australians trusted what was printed in the newspapers, and in a time where Australians trusted politicians.

That's not, that's not today. And so, when you lead with bipartisanship, you're just going to end up with a pretty lowest common denominator reform, and one of the reasons George that we issued the Uluru Statement from the Heart – I say ‘we’, but I was just a Constitutional lawyer along for the ride, but the old people and the people in the dialogues talked about needing to issue this statement to the Australian people, was because if you leave it to politicians, right, it's just a race to the bottom. And retail Australian politics kicks in, and it doesn't become about the substance or what we're trying to address in the nation for a particular group of people. It just becomes about their continual ongoing, kind of an adversarial battles between each other that Australians are just frankly, sick of.

We’re sick of the bickering, we’re sick of the way they carry on. It's why their primary votes have plummeted to the 30s, and why people voted for The Greens and the Teals and other people, because they want change, they want to make a difference. And all of our polling and research that we're doing shows something really clear. I think Craig is right, or the panel is right. The kind of ‘no’ tends to be baby boomers and the silent generation, and then you've got this huge cohort of ‘yes’, from Gen Z, millennials, Generation X, our multicultural brothers and sisters, Islam, Buddhists, Hindus. It's this extraordinary movement of Aussies, who in the research say that social change is a good thing. That's what they're saying. They're saying this will be a good thing for the nation. And then that batches us up against the 20 to 30% saying, “no change is good thing. Yeah, the status quo is the best thing”. Anyway, George, the bipartisanship thing really frustrates me as you know, because I don't think it's scrutinised enough.

I think it comes from the kind of eight out of 44 kind of analysis of what worked and what didn’t work, but the last successful referendum know social media. You know The Daily Telegraph used to come out morning, midday afternoon edition – Aussies believed what they read in the paper. There was no internet, there was huge levels of trust in public institutions back then and today, it’s at the lowest ever. Aussies don’t trust politicians and so you know, to take the bipartisanship record and apply it now, to me, just as I said – it shrinks us as a nation, and it makes us make decisions that aren't the best for the nation.

George Williams: Thanks, Megan. And I must admit that I mean, your point about politicians not reading the Voice in particular strikes a chord when it’s only 92 words. The Voice changes, but it’s pretty obvious not many people have read those 92 words because they say an awful lot of things in there that plainly aren’t.

Megan Davis: Well George, there’s been seven processes and 10 reports in 12 years, and I can assure you, the bulk of them have read none of it.

George Williams: Yeah, I can say one person who assiduously did read the Constitution at least but he had a reason for doing so – Lionel Murphy, the former Attorney-General in the Whitlam government, High Court judge but he was an insomniac. If you’re struggling to get to sleep tonight, I challenge you to get past section 25. I really find it difficult.

I think we’re going to get some questions now from the audience. So, we’re going to get the lights up so people don’t trip over. We’ve got a couple of mics. I’ll start with a question or two on Slido, if you’d like to ask a question, please. We’ve got a mic two here, and mic one there – just come up to the mic and I’ll get to in a sec. But firstly, I’ll go to a question from Slido and this one is, would we need to rewrite the Constitution completely, if we became a republic? And what process would this follow? So, Craig, is your vision for rewriting the whole thing? Or how do you see us progressing this?

Craig Foster: Well, you’ve done much more work in that than me George. So, you can…

George Williams: I can't answer the questions. I'm going to ask them, okay.

Craig Foster: No, so it’s not necessary. No.

Megan Davis: I can answer it.

Craig Foster: You can answer it. Megan, away you go.

Megan Davis: Yeah, so the last republic did require something over about 83 changes to the Constitution. And that’s because it was a kind of minimalist form of change, but you are kind of clicking over from a Constitutional monarchy to a republic, and a President in that sense. So yeah, it does require a lot of changes, a lot of cosmetic changes though.

So, I think George can talk to this better than be but certainly the Australian acts and other developments since, you know, 1901 I mean, we’ve moved slowly towards something that looks like independence but yeah, and this one is going to require a lot. But I guess my point, Craig and I’ll leave it back to you but on that point, we can’t allow the opposition – the ‘no’s’, the no changes to just add up changes and make out like it’s a really dramatic change when it’s not. And I think, that was part of the republic debate in 1999 and I think we need Aussies – like we’re trying to do with the Voice, let’s just be hard-headed reformists and just not get alarmed by all the sorts of tricks that the ‘no’ case might pull up to try and you know, stop change. And one of those was in 1999, and George knows better than me, I was out of the country, but they were adding up the number of changes and going, “oh my god, 99 changes”, and you know, “the world’s going to fall, well, the sky is going to fall in”. It's really important not to allow ourselves to fall victim to that again, so subject to what all of the new Constitutions will look like, and what all the new Aussies will say a republic looks like, because I think that conversation needs to be had. At the end of the day, yeah, it’s going to require substantial changes to the Constitution, but that’s okay. It’s okay.

George Williams: And the word Queen does appear a lot in the Constitution so that’s the larger part of it. I might start on mic two. If we get the question short and we’ll try and keep the answer short, just so we can get as many questions and answers in as possible. Thank you.

Audience: Thank you. I was very disappointed, I voted in the 1999 referendum and I was very disappointed. Do you remember voting, being disappointed? I don’t remember the wording of the actual question but I do remember that the syntax or, it was complicated, and can I ask my question is please, the people who are going to be advising and campaigning – please try and get that question as simple as possible. Can you please keep that uppermost in your mind that you will try and insist on that?

George Williams: Thank you. We’ll go to number one.

Audience: Is there a possibility that the republic.org model that you’ve come up with – is there a possibility that we could tinker with it a little bit and change it a little bit? I see a threat when it goes through parliaments. I find it as a threat, I don’t want it to go through that.

Craig Foster: Okay thank you. So, the gentleman is referring to a model that was prepared by the Australian Republic Movement previous to my co-chair personship which is called the Australian Choice Model and we’d welcome everyone going to republic.org.au to have a look at it. And what it demonstrates is a potential model based on research of over 10,000 Australians and what they wanted to see and in particular, the fact that a lot of Australians and this goes back to ‘99 – wanted to have some sort of democratic participation in that decision being made. What I’ll say to you, and everyone listening and on your former podcast, though, is that, as I said before, the model is for all Australians to find, and that is one part of the discussion, but only one part and we need to go through a process whereby we discuss all of the various types of models, all of the concerns and possibilities that we can contemplate. And as Australians, you and I are in those rooms formulating a model that works for us.

George Williams: So I think the answer is yes. There will be room for change, or at least the discussion that we might have. We'll go back to number two. Thanks.

Audience: Yeah so, I have an idea about basically how it will affect our identity as Australia and marginalised communities. So, my question is, do you think the question will become about white Australians? And how it will affect white Australians? Or do you think we will bring in more marginalised communities into the conversation?

Nyadol Nyuon: Thanks for that. That’s a really honest question. Thanks for that question. I think yes because they’re part of the Australian community and to some degree, they are about 80% of our parliament, media, and most of all institutions. So, I think that’s the point I was trying to say before that, whether we like it or not, we’ve defined who is Australian in a very particular way. And of course, when we’re talking about [a] republic, it challenged the definition of who we the people in this country are and, my approach, and there are people that might disagree, as always been that you’ll have those conversations right, and then they’re going to be difficult. They’re going to be frustrating.

But I would hope that if you leave the other person with an appreciation even though you disagree with them, you don’t intend to harm them. I hope that can be a way of having that conversation but I think fundamentally, yes, it’s about who are we – all the moving aspect of this country, who are we? Can we be something different? If it’s possible, how do we go about doing it? And what do we do with the challenges that comes from that? Because any change brings its own challenges along the way. Now, I think that the question of a republic future might be something that is inevitable.

You know, when the Queen began to reign, there was about 32 countries that were republics. By the time she died, there was only 14 and out of those 14, four are in the process of change, including Jamaica. That’s when I say change, that means they’re actually considering a referendum and the remaining six of them are in some form of change.

So, they’ve got Republican movement and they’ve also got senior politicians engaged in that process. But even if we leave the idea of it being an inevitable, I think that in the current situation we are in, we are already having discussions about trying to get foreigners to join Australian military because we can’t recruit enough. We’ve got shift in the geopolitical area; we’re no longer tied to an empire. In fact, they’re struggling economically, the position of the United States guaranteeing our stability within the region is questionable and so, I think even leaving aside the question of identity and stuff, practically, what that Australian existence looks like in the 21st century and I think that our possibility to survive and thrive as a country will be influenced by how we actually manage the complexity and the advantages we have as a country at the moment. So yes, it's going be a difficult question that might challenge the central identity of who we identify as Australia, but I think it has plenty of opportunity for us to. I feel like I've answered your question in a such a roundabout way. But I'll find you later in a very moment.

Craig Foster: Can I just say a couple of quick comments to that the opportunity to have a conversation with, if you’d like, real Australia – who we are, who the face of Australia is, and what our contemporary cultural demography is – it’s incredibly exciting and should never and can never be framed as one Australian against the other. It's about all of us and who we are in 2023, coming together to have that conversation, collectively.

The other thing about the conversation that’s so exciting and has to occur after the Voice rightly is that we are on the cusp of this movement in Australia for representation and access and, the reason why I’m so passionate about the real Australia coming forward is because you know, those calls are getting louder and so, I feel and yet, multicultural communities – the Australian Diversity Council, the media, Diversity Alliance and so on are becoming much more prominent and all of our communities giving us the message across all of our different cultures that we want to be seen, we want access, we want to speak and a voice, and we want to be represented.

And in 2022 last year, we saw, and I think Australia was deeply proud of the most representative, federal parliament in our history. Now, it doesn’t represent contemporary Australia but it’s a step forward and when we saw that, we recognise that this beautiful diversity is who we are and that where we’re going. That’s what the republic is about. It’s about having that conversation because that’s what our cultural communities across the country is trying to tell us. So, I feel as though that’s the next conversation for Australia and when we have that, it’s incredibly exciting to think about our new conception of ourselves and who we are, just look at this room – you know, exactly who we are coming to life in our Constitution and in every position of Australian life.

George Williams: Thank you and we’re going to run for another five minutes or so because we started a little bit late. I’m going to take one question from Slido and then I’ll come to microphone one. So, Megan, this one’s actually for you. If we became a republic, could we use the Indigenous flag as the new Australian flag? That’s the question from Slido.

Megan Davis: You'll have to ask the Commonwealth that they own the flag now.

George Williams: What are your thoughts as to whether it would be appropriate?

Megan Davis: It wouldn’t be up to me. It would be up to the Commonwealth. I’m not, you know, I don’t know if that’s appropriate. I do think we need a new flag though George, and I don’t know how you do that. I mean, you and I have spoken for 22 years about the importance of engaging Aussies in all sorts of things not the least the design of the flag so I’m all up for that. I think we need something exciting and inspiring and something that is inclusive. Whether that’s the Aboriginal flag, maybe not because obviously that has a very deep history with Aboriginal advocacy and land rights. But who knows the future? I can’t control the future, but we definitely need a new flag.

George Williams: Thanks Megan.

Megan Davis: That’s my diplomatic answer.

George Williams: Craig, you wanted to say something on this?

Craig Foster: I just want to communicate how extraordinarily strong and courageous and brilliant First Nation leaders have been across the country in particular, this year. And the reason is because we can’t underestimate the burden that they are carrying and that is – social change has proven to be difficult throughout our history, and we are wrestling with foundational issues that goes to the very identity of Australia. But the biggest gift I think that we've been given this year by First Nations leaders is the ability to actually listen, and to come to some discomfort, and to talk nationally about incredibly important issues. And yeah, we're going to need that in future and that's the gift that we're actually being given this year. That is, I'm hoping, and when you hear me speak, I'm also talking about Australians understanding of the diversionary tactics and our understanding of the misinformation and our ability to disseminate, you know, right from wrong, and, and to really understand the political process and the pushback better.

We’re learning about actually making change this year, you know, I hope that we and I’m optimistic that we get over that really important line but that’s going to put us in a position in future I hope where we become more skilled at having these conversations, because whether it’s about the flag or the anthem, or the other things, we have to push back against this, “oh well, you know nothing should change”. You know, and I think, and I hope this year, we’re becoming more skilled than that.

Megan Davis: George if I can just jump in, this was Craig's point. I mean, I think it’s an important one about how we learn to just have uncomfortable conversations because sometimes in a period of flux, you know, there will be groups that want to arm with each other and just because there’s tension at some point. As we get to a point where we understand each other’s positions, it’s not a bad thing, you know. It’s okay, for deliberation.

It’s the same as the Aboriginal dialogues where there was a lot of tension, agreement, disagreement, and we put it all into a record of meeting. And that’s how we slowly got towards consensus and Craig alluded to the Irish processes that we studied to design the deliberative dialogues meaning it’s good to get Aussies together and yarn about things, and it takes months and months or years to come to a position but we should feel comfortable with that without it being turned into some sort of negative adversarial thing by media or politicians. I think that is the way we should walk towards as a democracy because I think you’re going to end up with better decisions. If we have the time and space to have those yarns that aren’t comfortable. It’s okay to have some discomfort.

George Williams: Thanks, Megan. We’re going to take couple more question if we don’t get through many more. But number one, please.

Audience: In 1999, I voted against a republic, for two reasons. One, the issue of First Nations and Indigenous Australians, we couldn't go forward purporting to be a new republic without addressing that issue. Therefore, the Voice must come first. But the second reason was that the vast majority of Australians wanted to vote for their President, and we were told that was not going to happen, because it was too difficult. It's not too difficult. If people want to vote, you have to work out how it can be done. So my questions are two – one, how is it going to be done, that we as Australians can vote for our president and not have the parliament impose one of them on us? And secondly, if that's going to happen, we become a republic, you've got to work out what are the powers of the president? So those are my two questions – what are the powers of thePpresident? And how are we going to work out that we as Australians can vote for our President? Thank you.

Craig Foster: Great, thank you for the really important questions. I can answer that one pretty quickly is I think we discussed quite a lot tonight about all Australians coming to a model. That's a consensus among all of us, and that provides all of our communities and First Nations people and every Australian to have a say, and therefore, that's one very important view. And there are many, many other important views and we want to get into a conversation and a deliberation – the word that Megan rightly used as to what we want and what is right and I'm confident in Australians, I trust Australians. And I trust that process of us all coming together, and we'll find a model that works for us.

George Williams: And can I say, I’m absolutely confident as a constitutional lawyer, it can be drafted. The question is what the people want? As Craig is saying, there are no legal barriers here. The question is, what is the right answer? One more question, I think, and then we'll wrap up just because I want to let people get to their dinners and other things. But thank you, one more question.

Audience: We talked a lot, or you talked a lot tonight about the nuances of this discussion, as well as the ability for Australians to be able to get messy and have those messy, uncomfortable conversations. I'm just wondering what you think the media landscape is going to do or be able to cope with that level of complexity, discomfort, and nuance that we know is required for this to happen. So, I know Megan’s point earlier around, there was once upon a time The Daily Telegraph was the truth, and now we have a lot more diversity in the media. We’ve got social media really taking flight but that doesn’t necessarily equate unfortunately, to a democratic voice and things like that. So yeah, just interested in hearing about that.

Nyadol Nyuon: I think I separate the media in two spaces – I think social media and then traditional media. I don’t think traditional media would at all cope with a complex conversation. I think that over the years, internal challenges, the 24-hour news cycles have really narrowed media to be more about rage, at the very least, if not rage, what grabs attention? And sometimes, the serious things don’t grab attention.

So, I think that it won’t, I think we would definitely fall back to that – the cultural wars, conversations or, ‘woke’ with a kind of one narrative where you really don’t get to have the debate. But I do think that social media is interesting because it’s quite subversive, sometimes of mainstream media and you can have a lot of ongoing conversations there, but it can also be highly sold to you know, silos so that you have a group of people who are just conversing against themselves. Now, I think that despite those challenges, I think we should still attempt to have these conversations in different platforms, whether it’s university, social media and even traditional media and finding other platform. The reason I say that is that I think if you look back, historically, change will always face challenges, no matter what it is. These are the challenges of our time; we just have to reconcile ourselves to them and work though them. If so, despite the media landscape, I think you have those debates and sometimes you lose, but sometimes you win. But if you don’t try, you will never know.

George Williams: I think we’re going to wrap it up there. And I’m sorry for the people who haven’t been able to ask more questions but look, this was just a teaser. The debate is going to go for the next couple of years and we have promised this would run shorter than the coronation and I really do want to keep that. But thank you for joining us, I mean, it gives us great heart to see so many people here tonight interested in this topic. I’d really like to thank Craig, Megan and Nyadol for having this conversation with us tonight and telling us their thoughts on the case for a republic. The UNSW bookshop is in the foyer and encourage you not to leave without at least one book in your possession from the UNSW bookshop. If you’d like to hear about more upcoming events or the podcast, don’t forget to subscribe to the UNSW Centre for Ideas which hosts many of these great events, and thank you for coming. Thanks to our panelists. I hope you enjoy the night.

UNSW Centre for Ideas: Thanks for listening. This event was presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and the Australian Human Rights Institute. For more information, visit centreforideas.com and don’t forget to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts

-

1/5

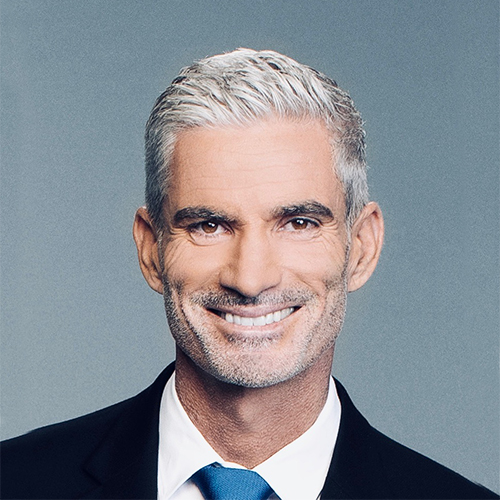

Craig Foster

-

2/5

Nyadol Nyuon

-

3/5

Megan Davis

-

4/5

George Williams

-

5/5

The Panel

Megan Davis

Megan Davis is a Professor of Law, holds the Balnaves Chair in Constitutional Law and is Pro Vice-Chancellor Society at UNSW Sydney. She is a globally recognised expert on Indigenous peoples’ rights, and was a member of both the Prime Minister’s Referendum Council and the Prime Minister’s Expert Panel on the Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution. She also designed the deliberative dialogues and chaired the Referendum Council’s sub-committee for the First Nations regional dialogues, and the First Nations National Constitutional Convention in 2017. Since 2017 she has continued her legal work and community legal education via the Indigenous Law Centre UNSW Sydney. She was an expert member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (2011–2016) and is currently an expert member and Chair of the United Nations Human Rights Council’s Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous peoples (2017–2022). In 2022 she was a co-recipient of the Sydney Peace Prize for the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Craig Foster

Following a decorated football career as Australia’s 419th Socceroo and 40th Captain, Craig Foster has become one of Australia’s most respected sportspeople, and is a broadcaster, social justice advocate and human rights campaigner.

Craig represented Australia at senior level on 29 occasions, including as Captain. Following retirement, he became one of Australia’s most respected sports broadcasters, a member of the Australian Multicultural Council, NSW Australian of the Year 2023 and is well known for his campaign to free Hakeem al-Araibi, a young Bahraini refugee and the Afghan Women’s National Football Team who escaped the Taliban and now play together in Melbourne. Craig holds a law degree and Masters of International Sport Management, is the Patron of Australia’s First Nations representative football teams, the IndigenousRoos and Koalas, and is the Co-Chair of the Australian republic Movement alongside First Nations sporting legend, Nova Peris OAM.

Nyadol Nyuon

Nyadol became Director of Victoria University’s Sir Zelman Cowen Centre in January 2022, after more than a decade working in community development and advocacy. Her work focuses on legal reform, social justice, human rights and multiculturalism. A refugee to Australia, Nyadol went on to complete a Bachelor of Arts at Victoria University and a Juris Doctor at the University of Melbourne, before spending six years in commercial law at Arnold Bloch Lieber. She is a regular media commentator, having appeared on the ABC’s The Drum and Q&A; and has written for publications like The Age, Guardian Australia and The Saturday Paper. Nyadol has won several prestigious awards, including the 2019 Victorian Premier’s Award for Community Harmony and the 2019 Diversity and Inclusion Award in The Australian Financial Review’s 100 Women of Influence Awards. In June 2022, Nyadol received a Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM) for service to human rights and refugee women.

George Williams (Host)

George Williams AO is the Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Anthony Mason Professor and a Scientia Professor at UNSW. He has served as Dean of UNSW Law and held an Australian Research Council Laureate Fellowship and visiting positions at Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto, Columbia University Law School in New York, and Durham University and University College London in the United Kingdom.

He has written extensively on constitutional law and public policy, with books including Everything You Need to Know About the Uluru Statement from the Heart with Megan Davis, How to Rule Your Own Country: The weird and wonderful world of micronations with Harry Hobbs, Australian Constitutional Law and Theory, The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia and Human Rights under the Australian Constitution. He has appeared as a barrister in the High Court in many cases over the past two decades, including on freedom of speech, freedom from racial discrimination and the rule of law. He has also appeared in the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal of Fiji, including on the legality of the 2000 coup. He is a media commentator on legal issues and a columnist for The Australian.