Abraham Verghese: The Covenant of Water

I always felt that if something that suddenly was happening to a character was surprising to me – I don't mean cheap surprise, but surprise in terms of an insight into a character's heart or what made them who they were – then it would also be compelling to the reader.

Physician and writer Abraham Verghese, author of Cutting for Stone, crafts a masterly narrative of three generations of a family in Kerala, through the eyes of a young girl, from her arranged marriage at the turn of the 20th century to her emergence as the matriarchal figure Big Ammachi.

Solving the mystery of a family affliction – in every generation, at least one person dies by drowning – the book brings to life a vanished past and the impact of change on lives and communities.

Examine the marriage of medicine and literature with Abraham, joined by host Roanna Gonsalves.

Presented by Sydney Writers' Festival and supported by UNSW Centre for Ideas.

Transcript

UNSW Centre for Ideas

UNSW Centre for Ideas

Roanna Gonsalves

Hello everyone. Welcome to the Sydney Writers Festival 2024. My name is Roanna Gonsalves and I'm delighted to welcome you all here to a conversation with Abraham Verghese, the author of The Covenant of Water. I would like to acknowledge the Gadigal people of the Era nation, the traditional custodians of this land, and pay my respects to the elders, past and present and to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who are here with us today.

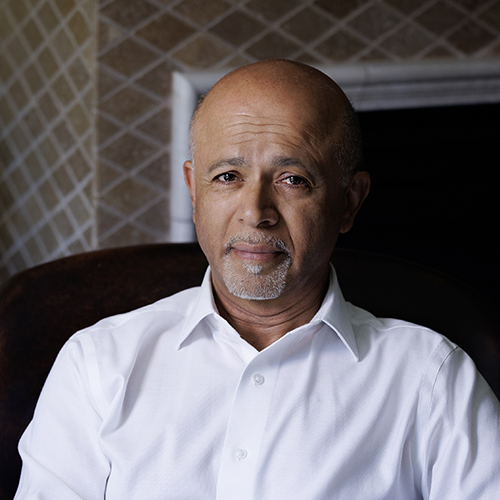

Abraham Verghese is a graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop and the author of books including My Own Country and The Tennis Partner. His most recent novel, the book that we're going to be talking about this evening, is The Covenant of Water, and it was selected for Oprah's Book Club and has already spent six months on the New York Times bestseller list.

His 2009 novel Cutting for Stone sold more than 1.5 million copies in the US alone, and it was translated into more than 20 languages and is being adapted for film by Anonymous Content. Abraham was awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2016, and has received five honorary degrees and lives and practices medicine in Stanford, California, where he is the Linda R. Meier Linda and Joan F Lane Provostial Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Not only is he a doctor, he's also a professor of medicine, Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine, and he writes bestselling books that are on the New York Times bestseller lists for months and months. Welcome, Abraham. It's such an honour to have you here with us. Thank you for the gift of your writing. And thank you for writing this book.

Abraham Verghese

Thank you so much for having me. And thank you for coming.

Roanna Gonsalves

I'll tell you what the publisher's website says about this book, and then I'll tell you why I love it. So, according to the publisher's website, 'spanning the years 1900 to 1977, The Covenant of Water follows a family in southern India that suffers a peculiar affliction in every generation. At least one person dies by drowning.' And this book is set in Kerala.

Many of you have either been to Kerala or are from Kerala or have heard of Kerala, it's a place where water is everywhere. 'At the turn of the century, a 12 year old girl grieving the death of her father is sent by boat to her wedding, where she will marry her 40 year old husband and see him, actually, she will meet him for the first time.

From this poignant beginning, the young girl and future matriarch known as Big Ammachi will witness unthinkable changes at home and at large over the span of her extraordinary life, full of the joys and trials of love and the struggles of hardship.' I told you, it's going to be like an edge of the seat kind of conversation, a shimmering evocation of a lost India and of the passage of time itself.

'The Covenant of Water', says the publisher, 'is a hymn to progress in medicine and to human understanding, and a humbling testament to the hardships undergone by past generations for the sake of those alive today. Imbued with humour, deep emotion, and the essence of life, it is one of the most masterful literary novels published in recent years.' I love this book for many reasons.

It's set in a part of the world that is very dear to me, close to where I grew up. It's a love letter to Malayalis. It's a love letter to Kerala. It's a love letter to medicine. It's a critique of the caste system and of the virtue signalling of the upper castes. It's a critique of the way indigenous people are treated.

A rendering of the effects of the loss of land rights for the Paniyan of the Wayanad in Kerala? There are many echoes here in Australia, as we all know. It's a critique of religion, but it's not a critique of faith in its purest sense of the term. It's a whopper of a book, 715 pages. I must admit, I thought, okay, I'll just skip a few pages just to get to the end.

You know, but life's too short for boring books. But actually, I could not. I tried to skip, but if I skipped a sentence and I could not, I could... I needed to read it, before I went to the next sentence. Because, really, Abraham Verghese is a master plotter. I don't know about in real life, but definitely on the page. A masterful storyteller.

I could not skip a few pages, even though that was my intention to get through the book. I had the pleasure of enjoying this book over 3 or 4 days, but you can prolong the pleasure. You know, you kind of, you read it over the course of many days and immerse yourself in the absolutely stunning evocation of place that Abraham has rendered in the book.

Every word is essential to the book. It's a book about secrets. It's a book about water. It's a book about hands. Abraham I love the way you weave in these three concerns, making them swirl through the book. The biblical references through the hands of Doubting Thomas. Saint Thomas, who landed in India in the first century A.D. and converted many Indians to Christianity 2000 years ago.

Abraham, I'd love for you to read from the book. But first, would you please tell us a little bit about the world of the book, why you chose to set the story in these particular places? Because it's not just set in India. It's set in other particular part of the world as well. So I'd love for you to begin by telling us a little bit about why this story, why these places? Why these times?

Abraham Verghese

Sure. Well, first let me say I love what you just said about how it's a critique of religion, but not of faith. And I think, I was trying to write a book that pay tribute to some of the heroic women in my life, especially my two grandmothers who were, you know... I think all of us know people like this who are heroic, but unsung.

You know, the world will never know about their strength. Both these women suffered great adversity, lost sons, you know, to typhoid fever in one case, rabies in the other. And yet they went on and they became sort of pillars of so goodness and strength in their families. And I wanted to sort of follow their lives, if you like.

So the setting is between 1900 and 1977 is very deliberate. And when you tell a story like that - multiple generations - you almost can't... you know, you have to be true to the times. And it was a time of two world wars, tremendous change for India and that India was emancipated after, you know, centuries of colonial rule.

And then it was also a time of great medical progress. So, you know, tried to get all those things in together was the ambition of the novel very, very clearly. But I must say that as a physician, one of the great joys of practicing medicine for the last 40 years has been to sort of see how diseases that I, that we just had names for in medical school but didn't really understand over the course of decades, became, you know, much more clearly understood, the molecular basis defined and eventually, you know, biological therapies developed.

And I wanted to have that happen during the course of the novel, in a sense, with this one disease. So that was the grand ambition. I didn't quite know how I would pull it off you, but you make me sound like I had a great master plan. We can talk about that. You know, I thought I would read a paragraph, and I should tell you that I've always admired it when when writers managed to foreshadow the whole book in the first paragraph of the novel.

Now, I clearly had no such talent to do that. So I had to wait till about ten, 15 or 16 to come close to that. And so in this paragraph that I'm going to read you, we've begun in the head of a 12 year old bride, as you described on her way to the wedding. But all of a sudden, in this paragraph, after she's been married, we suddenly make this leap forward where, you know, she's now a grandmother.

And looking back. And in that moment, very, you know, leap forward and looking back, I try to foreshadow the whole book. And before I read it, I should also say that parenthetically, that I recorded the audiobook for this novel, which is not common. In fact, I would say all of us as readers should have a little red flag go off if you ever hear of an author reading their own fiction. Just because, you know, what do we know about what's forming a book? it's no accident that Meryl Streep just recorded Tom Lake by my friend Ann Patchett. Or that Brad Pitt recorded Cormac McCarthy's All the Pretty Horses, because these folks know how to present. So I said to my publishers, I want to audition for this.

And if you think I can be as good as some of the people you're going to line up, then I'd like to do it.

Because I was worried that people would mangle all the ethnic terms in there, and I just didn't think I could stomach that. And so I was lucky to be picked. I learned a tremendous amount.

And I'm telling you this because it's my reading sounds a bit over the top. If it sounds a bit thespian, it's because I was taught how to do some of these things, how to change the pitch of my voice to indicate a male or a female on the page and, you know, accents, but not to overdo the accents.

So with that preamble, here goes. Here's that paragraph. " 'Happened is happened'. Our young bride will say when she becomes a grandmother, and when her granddaughter asks for a story about their ancestors. The little girl has heard rumours that there's is a genealogy chock full of secrets and that her ancestors included slavers, murderers, and a defrocked priest. 'Child happened is happened and the past is past. And furthermore, it's different every time I remember it. I'll tell you about the future, the one you will make'. But the child insists. Where should the story begin? With doubting Thomas, who insisted on seeing Christ's wounds before he'd believe? With other martyrs to the faith? No. What the child clamours for is the story of their own family, of the widow's house into which her grandmother married a land locked dwelling in a land of water, a house full of mysteries.

But such memories are woven from gossamer threads, and time eats holes in the fabric. And these she must darn with myth and fable. The grandmother is certain of a few things. A tale that leaves its imprint on a listener is unavoidably about families. A tale that leaves its imprint on a listener and tells the truth about how the world lives, is about families victories and wounds and their departed, including the ghosts that linger.

A story must offer instructions for living in God's realm, where joy never spares one from sorrow. A good story goes beyond what a forgiving God cares to do. It reconciles families. It unburdens them of secrets, whose bond is stronger than blood. But in the revealing of the secrets, as in their keeping, secrets can tear a family apart. Thank you.

Roanna Gonsalves

Just gorgeous. And those of you who have read the book will know how beautifully this foreshadows what is to come. But Abraham, it also functions as a hook. It functions as a hook for us as readers. We want to know 'Oh what's going on here? What are these secrets?' And, what has happened in that time between the older Mariam becomes become Big Ammachi, from the time of her wedding to now, when she's saying these words to the granddaughter, the time that has lapsed. What what's happened in that time? And that's the book isn't. It's just functions like this beautiful book.

Abraham Verghese

Yes. You're right, in a sense, that is the book is the is the, three generations between the 12 year old bride and and and the granddaughter who grows up to be a physician. Let me say, I think there are several hooks to me. One of them that was sort of risky was beginning with a 12 year old bride.

You know, the second line of the book is the, the 12 year old bride's mother saying to her, 'The saddest day of a girl's life is the day of her wedding. But God willing, after that it gets better.' And you know, it's to start with the 12 year old girl is dangerous because for most readers, contemporary readers, you know, it's shocking.

And yet that was the true story of my great grandmother and to some degree, my grandmother. And of course, most of them are actually marrying 12 or 13 year old boys. They were just becoming children in a large household with many other children and paradoxically, their mother in laws became closer to them than their own mothers because they really got to know them over such a long time.

And for a girl, it was the saddest day of their life, because marriage also meant that you were leaving this house that you belong to, and you will no longer be a part of that house, and you would now be a member of another house. And to this day I've attended, you know, the ceremony where the bride leaves for the church, both in America and Kerala, and there's tears, you know, there's weeping because even though there's a great occasion about to happen, this moment and the day and leaving to the church is actually, in its own way, quite sad.

So I was playing against that grain, I was playing against the secrets I was playing against the unfolding of history with all its difficulties, two wars and British occupation. So lots of hooks if you like.

Roanna Gonsalves

Yeah, lots of hooks, lots of hooks. But I just want to say that, you're beginning with a 12 year old girl was not shocking to me. It worked as a hook in a different way. I thought, 'Oh my God, here we go again, child marriage, India, melodrama'. But actually, the more I read, even just on that first page, the complexity with which, and the love with which you have breathed these characters into being, that was the hook for me.

From the first page onwards, you can see the love that the writer has for every single character. And I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that, your process of imagining these characters into being with so much love and empathy?

Abraham Verghese

Yeah, actually, I mean, I meant to say that the 12 year old bride was a hook in the sense that, as you said conventionally, all of us will think, 'Oh my God, here we go'. But I wanted to play against the grain because she was marrying a 40 year old widower who had children and for her to evolve into the most, you know, lovely love story.

I'm biased, so I shouldn't I shouldn't brag about my own, my own love story there. But for her to evolve into, you know, really wonderful love story as I see it, I thought was the challenge. And yet I was also this time telling the true story of my great grandmother, who I never knew. And she was married at 12 to an older widower who basically, you know, had a few children.

But over time they had children together and by all accounts, and I never met her. I mean, people still talked about how wonderful and humorous and rich that marriage was, a model for people around and naturally he, did not live as long as she did, but she, she sort of carried the torch of that marriage for such a long time and that that was, you know, the joy. You ask about the characters developing.

And, you know, I think, I wanted to save time on this book by not spending the eight years I spent on the last book. I said 'I'm going to be efficient. I'm going to have this all plotted out'. But, you know, a strange thing happens when you develop your characters and, you know, you get to know them and especially when you put the character under some pressure, you know, you have this moment in mind where they're under pressure in some way - there is an axiom in writing that character is determined by the decisions taken under pressure.

That's true of life, too. I suppose. You know, when you put someone under pressure, the particular decision they make versus somebody else is what makes them unique. And so I would put my characters under pressure and I would almost immediately know that they were not going to take the path that I chose.

And so I had this wonderful whiteboard in my living room with the whole plot of the book lined up. Excuse me. And I would suddenly realise I just can't go that way. And so I would have to take a photograph of my whiteboard, erase it, and start again. And so I got to know my characters quite organically by watching them unfold.

And I have the greatest respect for writers who know the whole story and pretty much write it. I've had to do it this somewhat more painful, intuitive way. But I always felt that if something that suddenly was happening to a character was surprising to me. I don't mean cheap surprise, but surprise in terms of way of a insight into a, you know, a character's heart or what made them who they were then it would also be compelling to the reader.

Roanna Gonsalves

Oh yeah, for sure. It's just to put it mildly, it is a compelling book. It's just superb. from what you were just saying, I think, I think it's your particular stance on power that enables us as readers to encounter this book as an edge of the seat kind of book. And now it makes sense the way that you've just talked about the way you've created characters, let them develop organically.

Not in this way that you had planned on the whiteboard. I feel like you have this particular stance on the accumulation of power, whether it is systemic power, societal power, religious, the power that institutional religion has - or the power that one has over oneself. You are constantly, as a writer, making sure that, this power is not held on to for very long, whether it's for individual characters, it's with individual characters or whether it's systemic. And also the idea of power needing glory to be legitimate.

The bishops - there's a scene in the book, I think later on I'm not giving away the ending by saying this, but there's a hospital that needs to be erected. The bishops on the committee are more interested in their names on the plaque, and in ordering the plaque for the hospital's foundation, rather than ordering the medical supplies.

And because they understand very keenly that you need glory, in order for power to survive. But I was just interested in your ideas on power because it comes through throughout the book - your critique of religion, but not faith. Your critique of the caste system. I love that scene where, again, I don't want to give too much away, but there are these upper caste Brahmins who think that they're being really generous, but then they're put in their place by a particular character.

I won't give it away. You have the pleasure of reading it for yourselves. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about the way power is subverted in your book all the time, I feel, and that's what makes it so rich and such a beautiful, engaging read. One of the things that makes it so.

Abraham Verghese

Well, I'm probably going to disappoint you Roanna, but on the other hand, I think as a wonderful writer yourself, you're you will agree in part. And that is, you know, I have this theory that when you write a book or where does a book really exist? I think a writer provides the words. There's that one arc. The reader provides their imagination, and somewhere in middle space, with any luck, this fictional dream begins to take form and shape.

If the writer provides too many words, the reader feels kind of robbed. You know, they're like, there's not... They don't have the joy of imagining. On the other hand, if the writer doesn't provide enough words, then the whole thing becomes mysterious. You know, like, you know, Finnegans Wake. Who the hell knows what James Joyce was trying to do there? I've given up, you know?

But having done that, I feel that I'm not responsible for what readers make of it. I've been humbled by getting a thesis or a master's thesis is on my last novel where the, you know, the the candidate was writing extensively about my use of symbolism and archetype, and I was thinking, 'My God, if only I was that clever, if I really knew how to do all those things'.

So similarly, I have to confess, when you talk about my use of power, as you know, one isn't consciously thinking of any of those things as one writes. In fact, I was trying to be true to the times, but, you know, if you... if I just think about my childhood and my visits to my grandparents, they were inequities of power that I saw and was, you know, embarrassed for and my parents saw, but had been so used to it that it wasn't... They understood my point of view, but didn't really know what to be done. And my grandparents, who obviously saw none of it. So I think I was just trying to be true to the times, true to the colonial era, true to the, you know, hierarchies of power that exists in all our lives.

But I don't think I ever consciously sat there and said, 'Today I'm going to pursue the theme of of power'. But just to say, I'm really not that smart, and I'm just glad that it all sort of seems that way to you, which is incredibly important to me. Thank you.

Roanna Gonsalves

But it's also being incredibly true to the imaginative capacity. That's why your characters do unexpected things and surprise you as a writer, because you're open to them almost taking on a life of their own. But it's you being true to the imagination.

Abraham Verghese

I think when you when you really inhabit a character, well, then things emerge in the specific they sort of.. the specific becomes a demonstrate of the archetypal the, you know, at the moment, if you like. So I never write in terms of archetypes. I never write in terms of rules. But, you know, characters begin to embody them.

And, you know, for me, the great joy of reading is to read about a novel set in a completely foreign culture to me. And yet in the behaviour of these very different people, to see echoes of all the truths that you and I know to be you know.. somehow we sort of know this is right.

This is true. This is what our life feels like. You know? And I think it's a recognition that makes it such a joy to read if I've become a writer, which I never set out to be, that's another story. But it's because I love this feeling of, entering a world and having, you know, decades pass, you know, centuries pass, wars and this and that, and you put the book down and it's Tuesday. That feeling of being transported, of stopping time, maybe because time is so ever present in medicine, you know, the joy of being able to stop time in that fashion is truly a delight.

Roanna Gonsalves

I'd love for you to talk a little bit more about that. That link between the craft of practicing medicine and the craft of writing. I know that that that is something that you have spent a lot of time thinking about, but also in the in the writing of this book, if, you know anyone who wants to go to medical school, please do them a favour and get them this book.

It's, it made me want to become a doctor and it's too late, but, I think, it's just this beautiful rendering of the vocation of being a doctor of medicine. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that link.

Abraham Verghese

You're very kind. Thank you. You know, and I think I, I actually was always a reader. I didn't really have much other strengths in my schooling. I was a very indifferent student. But I loved to read, and I keep into medicine because of the book. And I think that's fairly typical of a certain generation of physicians. In the UK and the Commonwealth, it was often the Citadel by by, AJ Cronin.

In America, it was a book called Arrowsmith. For me, it was a book called Of Human Bondage. And it almost doesn't matter what the medical element was. I felt the strong sense of being called to medicine. I saw medicine as a romantic and passionate pursuit, and I really haven't stopped seeing it that way. And the only reason I became a writer is I was living through an incredible moment in HIV in a small town in Tennessee.

I'm an infectious disease specialist. And I wrote a scientific paper describing a very unique happening in that small town, which I thought was happening in every small town. And the scientific paper got a lot of attention. But I felt that the language of science didn't really begin to capture the tragic nature of that voyage, didn't begin to capture the grief of the families, didn't begin to capture my own heartache that watching this unfold again and again in young men's lives, primarily before we had treatment.

And so that's how I became a writer. I must say that I found as a writer that, I, since I came to it fairly late in life in my, you know, late 30s- but I had life experience to draw on. And I always think of what is medicine, but life plus plus, life on steroids, a life lived that is most acute.

I mean the privilege we have of, you know, watching people in their most crucial moments, it's overwhelming. It's just tremendous. And, writing has been a wonderful way to sort of try to process that. You know, I always think that I write in order to understand what I'm thinking, and I can just take a walk by the river and try to understand it.

But there's something magical about the act of writing. Call it the muse, the right brain, call it, you know, the gods, whatever you want. It is completely mysterious to me, and I love it for that reason. I will say that the craft of medicine, especially as an internist, you know, the ability to sort of take all these disparate details and, you know, bring them together in one whole, apply Occam's Razor to many different observations you're making, you know, always trying to create synthesis - one diagnosis - that has been helpful, within medicine, one of my passions is, is really examining the body carefully, reading the body as a text, if you like. So I think that kind of attention to detail has definitely helped in the training of being a writer, I suppose. But it has helped both ways that I think being a writer has helped me become a better physician, because I'm more and more sort of aware of what's unfolding.

I'm not not in terms of parasitising, what I see, but just more aware of how human beings are, because I've taken the time to try and really kind of digest that in a way you only get through writing. I hope that answers your question.

Roanna Gonsalves

Yeah. That's beautiful. Thank you for sharing that with us.

Applause

On a slightly different note, as you were speaking, I could hear Scotland in your voice. Tell us about the character of Digby.

Abraham Verghese

Yeah. You know, I don't really have any reason for Scotland in my voice except in the audiobook. I took pains to learn the Glaswegian accent and, you know, things like that. But, people have asked me, you know, in fact, in India a journalist asked me, 'Did you put in the Scottish character in order to appeal to Western readers?'

And I felt a bit offended by the question. I said, you know, here's the irony. You and I are speaking in the English language, and the good majority of readers are going to read your piece as well as my book are, you know, people who read in English and, you know, are sort of steeped in the tradition - the British tradition.

So it really wasn't catering to anybody. It's catering to you as much as it is to the Western reader in some other country. But more than that, it was also catering to, you know, was being true to the times. So just being true to the times, you know, if you think about medicine in India 1900 to 1977, it was all driven by the British.

The Indian Medical Service was British, with Indian trainees and writers coming up slowly through the system. So to have a Scottish character, to have a Swiss estate manager, to have a, you know, English surgeon or Anglo-Indian characters, it was all very, very organic and true to the era. I wasn't really that is their interpretation. Like the person who wrote the master's thesis, God forbid he's not wrong. And the fact that he saw it that way, that's his - that was his fictional dream. That's what it meant to him. And more power to him.

Roanna Gonsalves

And just a plug for people who do write master's theses and PhD thesis. This is how literature stays alive - through scholarship. So please read the literature, but also read the scholarship on the literature. That's why we're still reading Finnegans Wake, because people have read written about it... There are lots of questions for you. I have so many questions myself, but a beautiful comment here.

Someone has said, D Reddy has said, 'As someone who grew up in Madras, your paragraph describing the Madras sea breeze makes me laugh and cry and rejoice. Thank you.' And another comment. 'As a physician myself' says this not anonymous commenter, 'you've depicted the awe and nostalgia of studying anatomy in medical school'. Just wonderful. a question from Anthony Z.

'Thanks for your wonderful book and audiobook. Beautifully narrated over 36 hours. Did reading aloud provoke new feelings or reflections on writing and storytelling?'

Abraham Verghese

Yes. I mean, in the sense that, let me answer the last question... Before we get to the question, let me just say I'm so honoured by those comments about Madras and about being a physician. And although most physicians would agree that when we were doing anatomy, there was nothing joyful or nostalgic about it, but, looking back, it is a rite of passage that most of us look back on with something, hopefully nostalgia.

And, they say you should write what you know. I spent significant time in Madras, in Kerala, in Africa, the topic of my last book. So I tend to stay with things that I can truly speak to. The research alone only gets you so far. So anyway, to answer the last question, which was about - I'm blanking, what was the last?

Roanna Gonsalves

Did reading aloud when you were doing the audiobook /

Abraham Verghese

Ah yes.

Roanna Gonsalves

/ provoke new feelings or reflections on writing and storytelling?

Abraham Verghese

Yeah, it certainly did. So, I must say that I have never gone back and read any of my books. Only because the impulse is irresistible to take up a pencil and make corrections. So I'm robbed of reading experience because I'm too self-conscious and critical of what I produced. But in this case, recording the audiobook, I was forced to sort of live the story, but not not even that alone with a wonderful producer and a studio technician.

And, you know, when I was revising, there were many times I'd been tears every single time I got to certain places, even though I knew what was gonna happen, I'd be in tears, you know? And but this time it was me, the producer, the technician, all of us in tears. And I think it's made me much more conscious of the or the audio experience.

I mean, I've always been a writer, I imagine, very much like you, who, you know, who reads their work or aloud. Aloud or in my case, I have my, you know, my loved one read it to me, which allows me to experience it and immediately see the flaws. I think recording the audiobook made me even more conscious of the importance of how it really sounds, even more than the way it looks. How does it sound?

Roanna Gonsalves

Oh, the dialog is exceptional. It's just superb. I have to say, the dialog throughout the book, when characters speak directly to each other, just superb. And you know, it's just a testament to the care that you have taken over every single word and sentence. A couple of questions. One from someone who's asking 'Any advice for someone trying to be a doctor and a writer, too?'

Abraham Verghese

Let me tell you the advice I give to people who want to be writers. And everyone thinks I'm being facetious when I say this, but I'm not. I love my day job. I love what I do in medicine. It's not a painful thing. you know, there are painful aspects to it. More so I think, now than when we started.

But I think that the advice I give to writers who are people who want to be writers is get a good day job, one that you love. Because I think there's nothing harder on a writer than having to, you know, churn out a book for to pay a kid's college tuition or something like that.

And I've been spared that. I can take my time writing a book. I don't really have to, you know, be in a great hurry. Don't get me wrong. I want my books to do very well. I like, you know, it's important to me. But if nothing happened, I'd still be, you know, happy. And, I would still feel like I hadn't been robbed of anything.

So, my advice to physicians, I think all of us, many, many physicians, all physicians, perhaps have a novel in them. And in another context, some famous writer said, everybody has a novel in them, but most of those novels should stay inside of them. I don't think that's likely, because I think most people have a novel in them.

And.. but it takes an extraordinary amount of work, as you know, in my case, years of writing in certain directions and realising, well, that's not the novel. So at least for me, it's a slow process, much more complicated than most things I do. But on the other hand, if you do a little bit every day and you keep progressing, at the end of it, you'll have some pages and hopefully they're good.

So I wouldn't discourage anybody, but I would do it for the right reason. I mean, I feel incredibly blessed that my books are still in print and they're well-received. You know, it's by no means a given. But I should also tell you, for the... just to give the physicians their a dose of reality. I had no real support in my first couple of jobs in medical schools where I was writing.

It was something I did secretly. No one wanted to know about it. They didn't claim it. They saw it as a distraction. Even when the book did pretty well, it was like, 'Well, what's you know, why is he doing all this stuff' you know? So it's only when I finally came to Stanford that they saw it as a as a valuable sort of pursuit, academic pursuit, if you like, the equivalent of my colleagues research.

And so that was wonderful. Also, with this book, I got a contract for it about, you know, 12 years ago or so and from a major publisher with the big advance. And.. but I just felt like ultimately the I was too slow for them. The publisher wanted so many pages, they didn't really seem to care about what the story was in those pages as much as the number of pages, and I finally had to break the contract and leave that publisher.

Owe them - still owe them - the big advance that gave me. I'm on my way to paying that off soon, and I also had to shop around for another publisher. It was really a lot more angst than anybody once in their life. So I feel incredibly fortunate to be talking to you and having a live audience in Australia.

You know, I had reached a point, if this book ever got into print, I would have been so happy I had reached that point of desperation. So to have all these wonderful things happened to the book has been to gravy for me. You know, just enormously grateful.

Roanna Gonsalves

Thank you. We are grateful to you for writing the book and for the gift of your writing. There's a question from Sanchana who says, and you've, you've you've responded to this in different ways already. But I will ask it, 'Can you share a bit about your writing process and how you balance that with practicing medicine?' So I suppose on a day to day basis, you know, how do you how do you balance, the actual practice of medicine with the practice of writing?

Abraham Verghese

You know, I think when I started off, especially with the first book after Iowa, I took a break from my I gave up my tenured position, cashed it all in cash. My retirement, went to Iowa. But when I came back, my first teaching job back in academic medicine was in El Paso, Texas. Texas Tech University, a small, you know, small medical school.

And all they wanted for me was to be a clinician and see people in my specialty and take care of students and residents and the evenings and nights where my own. The weekends or my own, no pressure to produce NIH grants and all that. But I was a very busy clinician. And so but in a strange way, I felt that the busyness at work just brought an acuteness to the writing, because I only had so many hours to do it.

I didn't have infinite time. And so, in a funny way, when I was busiest earliest in my career, I felt the writing was just the most pressured in a in a nice way, so to speak. I'm a much more senior now. I, you know, I have a fair number of administrative duties. When I'm on the wards as a as a consultant, your equivalent to your running a ward team.

Then I'm very busy and there's no time to do anything else, but it comes in 1 or 2 week blocks. So there are many times when I can block out time. And, you know, but everybody asks if you have a routine, you write so many hours a day? I wish I did. I think I, I write when I can and when it moves me.

And if only I weren't so lazy and were able to write every single day for so many hours, I would be more productive. But, you know, I just.. I've just had to do it when I can and when the mood strikes, which is often not... you know, not ideal. I write on the computer, but then I edit on paper.

So even though the computer gives you this illusion that you have, you know, you can move anywhere in the novel, which you can, you can only do so pretty much 1 or 2 pages at a time. And I think there's something wonderful about every day, or all the time, you know, taking the whole manuscript and saying, you know, these 50 sheets really belong here.

And these hundred sheets are great, but they don't belong in this novel. And, you know, they go into their own file under your desk. And I think you need to me, I feel like you need the weight of the paper, the tactile thing for me to sort of feel what you're doing with this book. The computer gives you that illusion, but it also robs you of some kind of reality.

Roanna Gonsalves

We're almost out of time, but I want to ask one more question that came in from the audience, and that is about your next book. Are we allowed to know what the next book is about or how you going with it?

Abraham Verghese

I used to get very offended by that question because my immediate reaction would be, well, what's wrong with the book I just wrote? You know.

Roanna Gonsalves

It's so good that we want more.

Abraham Verghese

I realise this, you know, it's very disingenuous that it's been a year, but I must say, I don't really feel this compulsion to.. it's a very... you know, unique thing I think, to our society is that you you have a number one hits on the top of the charts. You know, the song, let's say immediately you're expected to follow it up.

And, you know, I know I will write, but the events around this book have been so magical that I don't know if I could ever have this happen in just this kind of magical way again, and I won't be under any illusion. In many ways, I think that's what happened with the last novel. It did so well.

The publisher saw me as this golden goose that's going to lay a golden egg. I succumbed to the illusion - I took the big advance. And I think I'm much better off just, you know, understanding that I will always write. Hopefully pretty soon something will start to take shape and take form. But, I certainly don't feel pressure to come up with another novel tomorrow.

If it all ends with this novel, you know, it would have been a great accomplishment for me personally. I really wouldn't want much more.

Roanna Gonsalves

That's beautiful. I want to finish up with a line not from the book, from, but from the notes. And the notes themselves are a masterclass in, I think, in humility and in also acknowledging what many writers and artists have said in the past, that all art is made from other art and very few, very few writers have the humility or the honesty to admit that.

But here you have extensive notes by Abraham Verghese, referencing the influences that have that have fed his imaginative labor in this work. But I just want to end this session with this line that you have used from the poet E.E. Cummings, and you've taken that line, but done something beautiful with it. When one of the characters expresses the same sentiments in, in different words, I won't tell you those words, you'; have to find them for yourselves in the book. But the words by E.E. Cummings that you were influenced by were 'I carry your heart with me'. And I think that's such a beautiful line. 'I carry your heart with me'. And it to me it it calls to mind and it resonates with what you said Abraham at the start of the session, which is that magical bond between the writer, the reader and the work and that bond actually is predicated on love and empathy and trust.

And so I want to say thank you so much. Thank you so much for the gift of your beautiful work. To the audience I cannot recommend this book highly enough. It's a long book, but it will give you such delight and such pleasure. I laughed and cried at many points in the book. You are a masterful storyteller, Abraham.

Abraham Verghese

Thank you so much. Writers like you and me, we wouldn't exist without readers. And thank goodness for festivals like this one, you know, the Sydney Writers Festival is just incredible. You guys are incredible for coming and supporting it. So thank you so much. Thank you for having me here. And, happy reading ahead for you. Thank you.

UNSW Centre for Ideas

Thanks for listening. This event was presented by the UNSW Centre for Ideas and the Sydney Writer's Festival. For more information visit unswcentreforideas.com

Image Gallery

-

1/3

-

2/3

-

3/3

Abraham Verghese

Abraham Verghese is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop and the author of books including My Own Country and The Tennis Partner. His most recent novel, The Covenant of Water, was selected for Oprah’s Book Club and has spent six months on The New York Times bestseller list. His 2009 novel, Cutting for Stone, sold more than 1.5 million copies in the US alone. It was translated into more than twenty languages and is being adapted for film by Anonymous Content. Abraham was awarded the National Humanities Medal in 2016, has received five honorary degrees and lives and practices medicine in Stanford, California where he is the Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine at the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Roanna Gonsalves

Roanna Gonsalves is an award-winning writer and educator with an interdisciplinary practice. She is the author of the critically acclaimed collection of short fiction, The Permanent Resident. Her series of radio documentaries about contemporary India, On the tip of a billion tongues, and her social-satirical radio essay Doosra: The life and times of an Indian student in Australia were commissioned and broadcast by ABC RN. She works as a Lecturer in Creative Writing at UNSW Sydney.